Մասնակից:Էլեն Հովհաննիսյան/Ավազարկղ11

Ժամանակակից ճարտարապետությունը (մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետություն, ճարտարապետական շարժում և ոճ) աչքի ընկավ 20-րդ դարում՝ ավելի վաղ Ար-դեկոի և ավելի ուշ պոստմոդեռնիստական շարժումների միջև ընկած ժամանակահատվածում։ Ժամանակակից ճարտարապետությունը հիմնված էր շինարարության նոր և նորարարական տեխնոլոգիաների վրա (մասնավորապես՝ ապակու, պողպատի և բետոնի օգտագործումը),ֆունկցիոնալիզմի սկզբունքը (այսինքն՝ այդ ձևը պետք է հետևի գործառույթին)ընտրել մինիմալիզմը և մերժել զարդը[1]:

Ըստ Լե Կորբյուզիեի՝ շարժման արմատները պետք է փնտրել Էժեն Վիոլետ լե դուկի ստեղծագործություններում[2]: Շարժումը առաջացավ 20-րդ դարի առաջին կեսին և դարձավ գերիշխող Երկրորդ համաշխարհային պատերազմից հետո մինչև 1980-ականները, երբ այն աստիճանաբար փոխարինվեց որպես ինստիտուցիոնալ և կորպորատիվ շենքերի հիմնական ոճ՝ հետմոդեռն ճարտարապետությամբ[3]:

Ծագում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ժամանակակից ճարտարապետությունը առաջացել է 19-րդ դարի վերջում՝տեխնոլոգիայի, ճարտարագիտության և շինանյութերի հեղափոխության արդյունուքում: Մարդիկ ցանկանում էին կտրվել պատմական ճարտարապետական ոճերից և հորինել նորը:

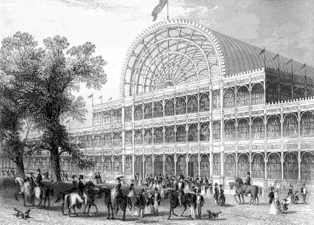

Ավելի թեթև և բարձր շինություններ կառուցելու համար նյութերի հեղափոխությունն առաջինն էր՝ չուգունի, գիպսաստվարաթղթի, թիթեղյա ապակու և երկաթբետոնի կիրառմամբ: Ձուլված ապակին հայտնագործվել է 1848 թվականին՝ թույլ տալով շատ մեծ պատուհանների արտադրություն:1851 թվականի Մեծ ցուցահանդեսում Ջոզեֆ Փաքսթոնի Բյուրեղապակյա պալատը երկաթով և ապակիներով շինարարության վաղ օրինակ էր, որին հաջորդեց 1864 թվականին առաջին ապակե և մետաղական վարագույրի պատը: Այս զարգացումները միասին հանգեցրին առաջին պողպատե շրջանակով երկնաքերին՝ տասը հարկանի Հոմ ինշուրանս բիլդինգին Չիկագոյում, որը կառուցվել է 1884 թվականին Ուիլյամ Լը Բարոն Ջեննիի[4] կողմից և հիմնված է Վիոլետ լե Դուկի աշխատանքների վրա։

Ֆրանսիացի արդյունաբերող Ֆրանսուա Կոինեն առաջինն է օգտագործել երկաթբետոնը, այսինքն՝ երկաթե ձողերով ամրացված բետոնը, որպես շենքերի կառուցման տեխնիկա[5]: 1853 թվականին Կոինեն կառուցեց առաջին երկաթբետոնե կառույցը՝ չորս հարկանի տուն Փարիզի արվարձաններում։[5]Հետագա կարևոր քայլը արեց Էլիշա Օտիսը, նա ստեղծեց անվտանգ վերելակ, որն առաջին անգամ ցուցադրվեց 1854 թվականին Նյու Յորքի Քրիստալ Փելս ցուցահանդեսում, որը բարձրահարկ գրասենյակները և բազմաբնակարան շենքերը իրական դարձրեց[4]:Նոր ճարտարապետության մեկ այլ կարևոր տեխնոլոգիա էր էլեկտրական լույսը, որը զգալիորեն նվազեցրեց 19-րդ դարում գազի հետևանքով առաջացած հրդեհների բնածին վտանգը[4]:

-

Կառլ Ֆրիդրիխ Շինկելի (1832–1836) Բեռլինի Բաուակադեմիա: Այն համարվում է ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության նախահայրերից մեկը՝ համեմատաբար հարթեցված ճակատի շնորհիվ։

-

Բյուրեղապակյա պալատը (1851) առաջին շենքերից էր, որն ուներ ապակե պատուհաններ, որոնք պատված էին չուգունե շրջանակով:

-

Երկաթբետոնից կառուցված առաջին տունն է, որը նախագծել է Ֆրանսուա Կոնյեն (1853) Փարիզի մերձակայքում գտնվող Սեն-Դենիում:

-

Էյֆելյան աշտարակի կառուցման շրջանը: է (օգոստոս 1887–89)

Նոր նյութերը և տեխնիկան ոգեշնչեցին ճարտարապետներին՝ կտրվել նեոկլասիկական? և էկլեկտիկ մոդելներից, որոնք գերիշխում էին եվրոպական և ամերիկյան ճարտարապետությունից 19-րդ դարի վերջին, հատկապես էկլեկտիցիզմը, վիկտորիանական և էդվարդյան ճարտարապետությունը և Beaux-Arts ճարտարապետական ոճը[6]:Անցյալի հետ այս խզումը հատկապես հորդորում էր ճարտարապետության տեսաբան և պատմաբան Էժեն Վիոլետ-լե-Դուկը:1872 թվականի իր «Entretiens sur L'Architecture» գրքում նա հորդորեց. «Օգտագործեք մեր ժամանակների կողմից մեզ տրված միջոցներն ու գիտելիքները, առանց միջամտող ավանդույթների, որոնք այսօր այլևս կենսունակ չեն, և այդ կերպ մենք կարող ենք բացել նոր ճարտարապետություն: Յուրաքանչյուր գործառույթ ունի իր նյութը,յուրաքանչյուր նյութ՝ իր ձևն ու զարդարանքը[7]: Այս գիրքը հետք թողեց ճարտարապետների մի սերնդի վրա, ներառյալ Լուի Սալիվանը, Վիկտոր Հորտան, Հեկտոր Գիմարդը և Անտոնի Գաուդին[8]:

Վաղ մոդեռնիզմը Եվրոպայում (1900–1914)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Չարլզ Ռենի Մակինտոշի Գլազգոյի արվեստի դպրոց(1896–99)

-

Օգյուստ Պերրե, Փարիզ-ամուր,բազմաբնակարան շենք(1903)

-

Ավստրիական փոստային խնայողության բանկ Վիեննայում Օտտո Վագներ (1904–1906)

-

Փիթեր Բեհրենսի ԱԷԳ Տուրբինե գործարանը (1909)

-

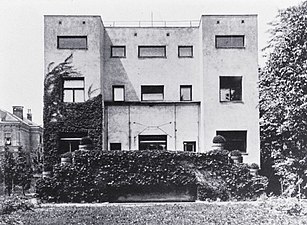

Շտայների տունը Ադոլֆ Լոոսի գլխավոր ճակատը Վիեննայում (1910)

-

Ստոկլետի պալատ, Յոզեֆ Հոֆման, Բրյուսել (1906–1911)

-

Չամպս - Էլսես թատրոն Փարիզում Օգյուստ Պերրե (1911–1913)

-

Անրի Սովաժի (1912–1914) աստիճանավոր բետոնե բազմաբնակարան շենք Փարիզում(1912–1914)

-

Գինսբուրգի երկնաքերը Կիևում (1910–1912) Ադոլֆ Մինկուսի և Ֆյոդոր Տրուպիանսկիի կողմից, տանիքի բարձրությամբ Եվրոպայի ամենաբարձր շենքը մինչև 1925 թվականը։

-

Մաքս Բերգ (1911–1913) Վրոցլավի հարյուրամյակի սրահը

-

Գերմանացի ճարտարապետ Բրունո Տաուտի ապակե տաղավարը Քյոլնում (1914)

19-րդ դարի վերջում մի քանի ճարտարապետներ սկսեցին մարտահրավեր նետել ավանդական Beaux Arts-ին ?և Neoclassical ?ոճերին, որոնք գերակշռում էին ճարտարապետության մեջ Եվրոպայում և Միացյալ Նահանգներում:Գլազգոյի արվեստի դպրոցը (1896–99), որը նախագծվել է Չարլզ Ռենի Մակինտոշի կողմից, ուներ ճակատ, որտեղ գերակշռում էին պատուհանների մեծ ուղղահայաց բացվածքները[9]:Արտ նուվան? մեկնարկվել է 1890-ականներին Վիկտոր Հորտայի կողմից Բելգիայում և Հեկտոր Գիմարդի կողմից Ֆրանսիայում, այն ներմուծեց զարդարման նոր ոճեր՝ հիմնված բուսական և ծաղկային ձևերի վրա:Բարսելոնայում Անտոնիո Գաուդին ճարտարապետությունը պատկերացրեց որպես քանդակի ձև: Բարսելոնայի Քասա Բատլոի ճակատը (1904–1907) ուղիղ գծեր չուներ,այն պատված էր քարե և կերամիկական սալիկների գունագեղ խճանկարներով[4]:

Ճարտարապետները նաև սկսեցին փորձարկել նոր նյութեր և տեխնիկա, ինչը նրանց ավելի մեծ ազատություն տվեց նոր ձևեր ստեղծելու համար:1903–1904 թվականներին Փարիզում Օգյուստ Պեռեն և Անրի Սովաժը`բազմաբնակարան շենքեր կառուցելու համար սկսեցին օգտագործել երկաթ և բետոն , որը նախկինում օգտագործվում էր միայն արդյունաբերական կառույցների համար [10]:Տարբեր ձևերի վերածվող երկաթբետոնը, որը կարող է հսկայական տարածություններ զբաղեցնել, առանց հենասյուների օգնության`փոխարինելու եկավ քարին և աղյուսին,հանդիսանալով, որպես ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության առաջնային նյութ:Պերրեի և Սվաժի առաջին բետոնե բազմաբնակարան շենքերը պատված էին կերամիկական սալիկներով, բայց 1905 թվականին Պերրեն կառուցեց առաջին բետոնե ավտոկայանատեղը Փարիզի դե Պոնթիե փողոց 51 հասցեում: Այստեղ բետոնը մաշված էր, իսկ բետոնի միջև ընկած տարածությունը լցված էր ապակե պատուհաններով։ Անրի Սովաժն ավելացրեց ևս մեկ շինարարական նորամուծություն Փարիզի Վավին փողոցի բազմաբնակարան շենքում (1912–1914 թթ.); Երկաթից և բետոնից շենքը աստիճաններով էր, յուրաքանչյուր հարկը ետ էր ներքևի հարկից`այտպես ստեղծելով մի շարք սանդղափուլեր: 1910-ից 1913 թվականներին Օգյուստ Պերրեն կառուցել է Ելիսեյան դաշտերի թատրոնը, որը երկաթից և բետոնից պատրաստված շինարարության գլուխգործոց է, որի ճակատին արվել են Արտ Դեկո քանդակագործական հարթաքանդակներ Անտուան Բուրդելի կողմից:Բետոնե շինարարության շնորհիվ ոչ մի սյուն չի փակել հանդիսատեսի տեսադաշտը դեպի բեմ[10]:

Վիեննայում նոր ոճի մեկ այլ նախաձեռնող էր,Օտտո Վագները:Իր «Մոդեռն Արքիթեքթը» (1895) գրքում նա կոչ էր արել ավելի ռացիոնալիստական ճարտարապետության ոճ՝ հիմնված «ժամանակակից կյանքի»վրա[11] :Նա նախագծել է մետրոյի ժամանակակից դեկորատիվ կայարանը Կառլսպլացում, Վիեննայի (1888–89), այնուհետև դեկորատիվ Արտ Նուվո նստավայրը՝ Մաժոլիկա Հաուսում (1898), նախքան Ավստրիական Փոստային Խնայողական բանկում անցնելը շատ ավելի երկրաչափական և պարզեցված ոճի, առանց զարդարանքի։Վագները հայտարարեց, որ մտադիր է ցույց տալ շենքի գործառույթը արտաքին տեսքով։ Երկաթբետոնի արտաքին մասը պատված էր մարմարե սալիկներով, որոնք ամրացված էին փայլեցված ալյումինի պտուտակներով:Ինտերիերը ուղղակի ֆունկցիոնալ և պահեստային էր, պողպատից, ապակուց և բետոնից պատրաստված մեծ բաց տարածություն էր, որտեղ միակ զարդարանքը հենց կառույցն էր[4]:

Վիեննացի ճարտարապետ Ադոլֆ Լոոսը նույնպես սկսեց իր շենքերից հեռացնել որոշ զարդեր:Նրա Շտայների տունը, Վիեննայում (1910 թ.), օրինակ էր այն, ինչ նա անվանում էր ռացիոնալիստական ճարտարապետություն. այն ուներ հասարակ սվաղով ուղղանկյուն ճակատ՝ քառակուսի պատուհաններով և առանց զարդանախշերի։ Նոր շարժման համբավը, որը հայտնի դարձավ որպես Վիեննայի Անջատում, տարածվեց Ավստրիայի սահմաններից դուրս: Յոզեֆ Հոֆմանը, Վագների աշակերտը, 1906–1911 թվականներին Բրյուսելում կառուցեց վաղ մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետության ուղենիշը՝ Պալաիսն Ստոցլետ։ Նորվեգական մարմարով պատված աղյուսից կառուցված այս նստավայրը կազմված էր երկրաչափական բլոկներից, թևերից և աշտարակից։ Տան դիմաց մեծ լողավազանն արտացոլում էր նրա խորանարդ ձևերը։ Ինտերիերը զարդարված էր Գուստավ Կլիմտի և այլ նկարիչների նկարներով, և ճարտարապետը նույնիսկ նախագծեց հագուստ ընտանիքի համար, որպեսզի համապատասխանի ճարտարապետությանը:[4]

Գերմանիայում մոդեռնիստական արդյունաբերական շարժումը՝ Դոչեր Վերկբուն (Գերմանական Աշխատանքի Ֆեդերացիա) ստեղծվել է Մյունխենում 1907 թվականին ականավոր ճարտարապետական մեկնաբան Հերման Մութեզիուսի կողմից: Նրա նպատակն էր համախմբել դիզայներներին և արդյունաբերողներին, արտադրել լավ ձևավորված, բարձրորակ արտադրանք և այդ ընթացքում հորինել ճարտարապետության նոր տեսակ [12] :Կազմակերպությունն ի սկզբանե ուներ տասներկու ճարտարապետներ և տասներկու բիզնես ֆիրմաներ, սակայն արագ ընդլայնվեց:Ճարտարապետների թվում են Փիթեր Բեհրենսը, Թեոդոր Ֆիշերը (ով եղել է նրա առաջին տնօրենը), Յոզեֆ Հոֆմանը և Ռիչարդ Ռիմերշմիդը[13]:1909 թվականին Բեհրենսը նախագծեց մոդեռնիստական ոճի ամենավաղ և ամենաազդեցիկ արդյունաբերական շենքերից մեկը՝ ԱԷԳ տուրբինային գործարանը, որը պողպատից և բետոնից ֆունկցիոնալ հուշարձան էր:1911–1913 թվականներին Ադոլֆ Մեյերը և Վալտեր Գրոպիուսը, ովքեր երկուսն էլ աշխատել էին Բեհրենսում, կառուցեցին ևս մեկ հեղափոխական արդյունաբերական գործարան՝ Ֆագուսի գործարանը Ալֆելդ ան դեր Լայնում, մի կառույց առանց զարդանախշերի, որտեղ ցուցադրված էր բոլոր շինարարական տարրերը։Վերկբունդը կազմակերպեց մոդեռնիստական դիզայնի խոշոր ցուցահանդես Քյոլնում 1914 թվականի օգոստոսին Առաջին համաշխարհային պատերազմի սկսվելուց ընդամենը մի քանի շաբաթ առաջ: 1914 թվականի Քյոլնի ցուցահանդեսի համար Բրունո Տաուտը կառուցեց հեղափոխական ապակե տաղավար [3]:

Վաղ ամերիկյան մոդեռնիզմ (1890s–1914)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Ուիլլիամ Հ. Ուինսով Տուն, Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթ, Գետի անտառ Իլինոյս (1893–94)

-

Արթուր Հերթլի տունը Օուք Պարկում, Իլինոյս (1902)

-

Լարկին վարչակազմ շինություն Ֆրանկ Լիոյդ Ուայթ, Բուֆֆալո, Նյու Յորք(1904–1906)

-

Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթի «Ռոբի տունը», Չիկագո (1909)

Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթը շատ ինքնատիպ և անկախ ամերիկացի ճարտարապետ էր, ով հրաժարվեց որևէ ճարտարապետական շարժման մեջ դասակարգվելուց:Ինչպես Լե Կորբյուզիեն և Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոեն, նա չուներ պաշտոնական ճարտարապետական կրթություն:1887-ից 1893 թվականներին նա աշխատել է Չիկագոյի Լուի Սալիվանի գրասենյակում, ով Չիկագոյում առաջին բարձրահարկ պողպատե շրջանակով գրասենյակային շենքերի ստեղծման առաջին պիոնեռ է եղել?, և ով ասել է, որ «ձևը հետևում է Ռայթը ցանկանում էր խախտել բոլոր ավանդական կանոնները:Նա հատկապես հայտնի էր իր Փրերի Հաուսով, ներառյալ Ուինսլոու Հաուսը Ռիվեր Ֆորեստում, Իլինոյս (1893–94), Արթուր Հրթլի Հաուս (1902) և Ռոբիս Հաուս(1909),ընդարձակ, երկրաչափական բնակավայրեր՝ առանց զարդանախշերի, ուժեղ հորիզոնական գծերով, որոնք կարծես թե դուրս էին գալիս երկրից, և որոնք արձագանքում էին ամերիկյան տափաստանի լայն հարթ տարածություններին։ Նրա Լարկին բիլդինգը (1904–1906) Բաֆալոյում, Նյու Յորք, Յունիթի Թեմպլը(1905) Օակ Պարկում, Իլինոյսը և Յունիթի Թեմպը ունեին խիստ ինքնատիպ ձևեր և ոչ մի կապ պատմական նախադեպերի հետ[4]:

Վաղ երկնաքերեր[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Տան ապահովագրության շենքը Չիկագոյում, Ուիլյամ Լը Բարոն Ջեննի (1883)

-

Խոհեմ (երաշխիքային) շենք Լուի Սալիվանի կողմից Բուֆալոյում, Նյու Յորք (1896)

-

Ֆլատիրոն շենքը Նյու Յորքում (1903)

-

Վուլվորթ շրնքը և Նյու Յորքի երկնագիծը 1913 թվականին: Ներսից այն ժամանակակից էր, իսկ դրսում՝ նեոգոթիկ:

-

Կաս Գիլբերտի Վուլվորթ շենքի նեոգոթական թագը (1912)

19-րդ դարի վերջին ԱՄՆ-ում առաջին երկնաքերերը հայտնվել են 19-րդ դարի վերջում։Դրանք արդյունքն էին ամերիկյան արագ զարգացող քաղաքների կենտրոնում հողի պակասի և անշարժ գույքի բարձր արժեքի, ինչպես նաև նոր տեխնոլոգիաների, ներառյալ չհրկիզվող պողպատե շրջանակների և 1852 թվականին Էլիշա Օտիսի կողմից հայտնագործված անվտանգության վերելակի բարելավմումը: Առաջին պողպատե շրջանակով «երկնաքերը»՝ Դը Հոմ Ինշուրենս բիլդինգը գտնվում էր Չիկագոյում, այն տասը հարկանի էր: Այն նախագծել է Ուիլյամ Լը Բարոն Ջեննը 1883 թվականին և կարճ ժամանակում դարձել է աշխարհի ամենաբարձր շենքը: Լուի Սալիվանը Չիկագոյի սրտում, կառուցեց ևս մեկ մոնումենտալ նոր կառույց՝ Կարսոն, Պիրի, Սքոթ և Քոմփանի շենքը, 1904–1906 թվականներին: Թեև այս շենքերը հեղափոխական էին իրենց պողպատե շրջանակներով և բարձրությամբ, դրանց դեկորացիան վերցված էր Նեո-վերածննդի, Նեոգոթիկայի և Գեղարվեստի ճարտարապետությունից: Կաս Գիլբերտի նախագծած Վուլվորֆ կառույցը 1912 թվականին եղել է աշխարհի ամենաբարձր շենքը մինչև 1929 թվականին Քրայսլեր շինության: Կառույցը զուտ ժամանակակից էր, բայց դրա արտաքին տեսքը զարդարված էր նեոգոթական զարդանախշերով, ամբողջությամբ դեկորատիվ հենարաններով, կամարներով և սրունքներով, ինչի պատճառով այն կոչվեց «Առևտրի տաճար»[14]:

Մոդեռնիզմի վերելքը Եվրոպայում և Ռուսաստանում (1918–1931)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Առաջին համաշխարհային պատերազմից հետո երկարատև պայքար սկսվեց ճարտարապետների միջև, ովքեր պաշտպանում էին նեոկլասիցիզմի ավելի ավանդական ոճերը և Բոուզ-Արտս ճարտարապետական ոճը, և մոդեռնիստների միջև՝ Ֆրանսիայում Լե Կորբյուզիեի և Ռոբերտ Մալետ-Սթիվենսի, Վալտեր Գրոպիուսի և Լյուդվիգի գլխավորությամբ։ Միես վան դեր Ռոեն Գերմանիայում և Կոնստանտին Մելնիկովը նոր Խորհրդային Միությունում, ովքեր ցանկանում էին միայն պարզ ձևեր և վերացնել ցանկացած զարդարանք: Լուի Սալիվանը հռչակեց «Հետեվեք գործարույթին» աքսիոմը, որպեսզի ընդգծի ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության մեջ պարզության կարևորությունը: Արտ-Դեկոի ճարտարապետները, ինչպիսիք են Օգյուստ Պերրեն և Անրի Սովաժը, հաճախ փոխզիջման էին գնում երկուսի միջև՝ համատեղելով մոդեռնիստական ձևերն ու ոճավորված ձևավորումը:

Միջազգային ոճ (1920–1970)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Վիլլա Լա Ռոչե Ջիններեթ(այժմ՝ Հիմնադրամ Լե Քորբուսիեր) Լե Կորբյուզիեի կողմից, Փարիզ (1923–25)

-

Կորբւսիեր հաուս Վայսենհոֆ գույք Շտուտգարտ, Գերմանիա (1927)

-

Կիտրոհան տուն Վայսենհոֆում Շտուտգարտ,Գերմանիա Լե Կորբւզեի կողմից (1927)

-

Լե Կորբյուզիեի Վիլլա Սավոյե պոսիում (1928–31)

-

Վիլլա Պոլ Պուարե Ռոբերտ Մալետ-Սթիվենս (1921–1925)

-

Ռոբերտ Մալետ-Սթիվենսի «Վիլլա Նոյը Հյերեսում» (1923)

-

Հյուրանոց Մարտել րու Մալլետ-Ստեվենս, Ռոբերտ Մալլե-Սթիվենս (1926–1927)

Ֆրանսիայում մոդեռնիզմի վերելքի գերակշռող դեմքը Շառլ-Էդուարդ Ժաներետն էր՝ շվեյցարացի-ֆրանսիացի ճարտարապետ, ով 1920 թվականին վերցրեց Լե Կորբյուզիե անունը։ 1920 թվականին նա ամսագիրը անավանել է «Լեսպիրիտ Նովիուս» և եռանդով խթանել է ֆունկցիոնալ, մաքուր և որևէ ձևավորումից կամ պատմական ասոցիացիաներից զերծ ճարտարապետությունը:Նա նաև ծրագրված քաղաքների վրա հիմնված նոր ուրբանիզմի կրքոտ ջատագովն էր: 1922 թվականին նա ներկայացրել է երեք միլիոն մարդու համար նախատեսված քաղաքի դիզայն, որի բնակիչներն ապրում էին նույն վաթսուն հարկանի բարձր երկնաքերերում՝ շրջապատված բաց այգիներով: Նա նախագծել է մոդուլային տներ, որոնք զանգվածաբար կկառուցվեն նույն պլանով և կհավաքվեն բազմաբնակարան շենքերում, թաղամասերում և քաղաքներում: 1923 թվականին նա հրատարակեց «Դեպի ճարտարապետություն»՝ իր հայտնի կարգախոսով. «Տունը մեքենա է ապրելու համար»[15]: Նա անխոնջորեն քարոզում էր իր գաղափարները կարգախոսների, հոդվածների, գրքերի, կոնֆերանսների և ցուցահանդեսների մասնակցության միջոցով:

Իր գաղափարները պատկերացնելու համար 1920-ականներին նա կառուցեց մի շարք տներ և վիլլաներ Փարիզում և շրջակայքում: Դրանք բոլորը կառուցվել են ընդհանուր համակարգի համաձայն՝ հիմնված երկաթբետոնի և ինտերիերում երկաթբետոնե հենարանների վրա, որոնք աջակցում էին կառույցին, ինչը թույլ է տալիս ապակե վարագույրների պատերը ճակատին և բաց հատակի հատակագծերին՝ անկախ կառուցվածքից: Նրանք միշտ սպիտակ էին, և դրսից կամ ներսից նախշ ու զարդարանք չունեին։ Այս տներից ամենահայտնին Վիլլա Սավոյեն էր, որը կառուցվել է 1928–1931 թվականներին Փարիզի Պուասի արվարձանում։ Նրբագեղ սպիտակ տուփը, որը փաթաթված էր ապակե պատուհանների ժապավենով ճակատին, կենդանի տարածքով, որը բացվում էր ներքին պարտեզի և շրջակայքի վրա, բարձրացված սպիտակ սյուների շարքով մեծ մարգագետնի կենտրոնում, այն դարձավ պատկերակ։ մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետություն.՞[4]:

Բաուհաուսը և գերմանական Վորկբենտը (1919–1933)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Բաուհաուս Դեսաուի շենքը, նախագծված Վալտեր Գրոպիուսի կողմից (1926 թ.)T

-

ԱԴԳԲ արհմիութենական դպրոց Հաննես Մեյերի և Հանս Վիթվերի կողմից (1928–30)

-

Հաուս ամ Հոեմ , Վեիմեր Ջորջ Մուչ կողմից (1923)

-

Բարսելոնայի տաղավար (ժամանակակից վերակառուցում) Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոեի կողմից (1929)

-

Ուեսենհոֆ էստեր Շտուտգարտում, որը կառուցվել է գերմանական Վերկբունդի կողմից (1927 թ.)

Գերմանիայում առաջին համաշխարհային պատերազմից հետո հայտնվեցին երկու կարևոր մոդեռնիստական շարժումներ, Բաուհաուսը Վայմարի հիմնադրած դպրոցն էր, որը հիմնադրվել էր 1919 թվականին: Տնօրենը Վալտեր Գրոպիուսն էր: Գրոպիուսը Բեռլինի պաշտոնական պետական ճարտարապետի որդին էր, ով մինչ պատերազմը սովորել է Պետեր Բեհրենսի մոտ և նախագծել է մոդեռնիստական Ֆագուս տուրբինային գործարանը։ Բաուհաուսը նախապատերազմյան Արվեստի ակադեմիայի և տեխնոլոգիական դպրոցի միաձուլումն էր: 1926 թվականին այն Վայմարից տեղափոխվել է Դեսաու: Գրոպիուսը նախագծել էր նոր դպրոցը և ուսանողական հանրակացարանները, նոր զուտ ֆունկցիոնալ մոդեռնիստական ոճով, որը նա խրախուսում էր: Դպրոցը համախմբեց բոլոր ոլորտների մոդեռնիստներին, Ֆակուլտետի կազմում ընդգրկված էին մոդեռնիստ նկարիչներ Վասիլի Կանդինսկին, Ջոզեֆ Ալբերսը և Փոլ Կլեն և դիզայներ Մարսել Բրոյերը։

Գրոպիուսը դարձավ մոդեռնիզմի կարևոր տեսաբան՝ գրելով «Գաղափարը և շինարարությունը» 1923 թվականին: Նա ճարտարապետության ստանդարտացման և գործարանների աշխատողների համար ռացիոնալ ձևավորված բնակարանների զանգվածային շինարարության ջատագովն էր:1928 թվականին Սիմնս ընկերության կողմից նրան հանձնարարվեց Բեռլինի արվարձաններում աշխատողների համար բնակարան կառուցել, իսկ 1929 թվականին նա առաջարկեց կառուցել ութից տաս հարկանի բարակ աշտարակների հանրակացարաններ բանվորների համար։

Մինչ Գրոպիուսը ակտիվ էր Բաուհաուսում, Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոեն ղեկավարում էր մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետական շարժումը Բեռլինում: Նիդեռլանդներում Դե Ստիլ շարժումից ոգեշնչված՝ նա կառուցեց բետոնե ամառանոցների կլաստերներ և առաջարկեց ապակե գրասենյակային աշտարակի նախագիծ: Նա դարձավ գերմանական Վերկբունդի փոխնախագահը և Բաուհաոեսի ղեկավարը 1930-1933 թվականներին,առաջարկելով քաղաքային վերակառուցման մոդեռնիստական ծրագրերի լայն տեսականի: Նրա ամենահայտնի մոդեռնիստական աշխատանքը 1929 թվականին Բարսելոնայում կայացած միջազգային ցուցահանդեսի գերմանական տաղավարն էր:Դա մաքուր մոդեռնիզմի գործ էր՝ ապակե ու բետոնե պատերով ու մաքուր, հորիզոնական գծերով։ Թեև այն ընդամենը ժամանակավոր կառույց էր և քանդվեց 1930 թվականին, այն Լե Կորբյուզիեի Վիլլա Սավոյեի հետ միասին դարձավ մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետության ամենահայտնի տեսարժան վայրերից մեկը: Վերակառուցված տարբերակը այժմ գտնվում է Բարսելոնայի սկզբնական կայքում[4]:

Երբ նացիստները Գերմանիայում իշխանության եկան, նրանք Բաուհաուսը համարեցին որպես կոմունիստների մարզման վայր, և 1933 թվականին փակեցին դպրոցը:Գրոպիուսը թողեց Գերմանիան և գնաց Անգլիա, այնուհետև Միացյալ Նահանգներ, որտեղ նա և Մարսել Բրեյերը երկուսն էլ միացան ֆակուլտետին` Հարվարդի դիզայնի բարձրագույն դպրոցին և դարձել ամերիկացի հետպատերազմյան ճարտարապետների սերնդի ուսուցիչները:1937 թվականին Միես վան դեր Ռոեն նույնպես տեղափոխվեց Միացյալ Նահանգներ,նա դարձավ հետպատերազմյան ամերիկյան երկնաքերների ամենահայտնի դիզայներներից մեկը[4]:

Էքսպրեսիոնիստական ճարտարապետություն (1918–1931)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Großes Schauspielhaus-ի նախասրահը կամ Մեծ թատրոնը, Բեռլինում Հանս Պոելցիգի կողմից (1919)

-

Էյնշտեյնի աշտարակը Բեռլինի մոտ, Էրիխ Մենդելսոն (1920–24)

-

Էրիխ Մենդելսոնի The Mossehaus-ը Բեռլինում, streamline moderne-ի վաղ օրինակ (1921–23)

-

Չիլիի տունը Համբուրգում, Ֆրից Հոգեր (1921–24)

-

Հորսեշ էստատ հանրային բնակարանային նախագիծ Բրունո Տաուտի կողմից (1925)

-

Երկրորդ Գյոթեանումը Դորնախում Բազելի մոտ (Շվեյցարիա) ավստրիացի ճարտարապետ Ռուդոլֆ Շտայների կողմից (1924–1928)

-

Հետ Սշիպ բազմաբնակարան շենք Ամստերդամում Միշել դե Կլերկի կողմից (1917–1920)

-

Դե Բիջենկորվ խանութ Հաագայում Պիետ Կրամերի կողմից (1924–1926)

Էքսպրեսիոնիզմը, որը հայտնվեց Գերմանիայում 1910-ից 1925 թվականներին, հակաշարժում էր Բաուհաուսի և Վերկբունդի խիստ ֆունկցիոնալ ճարտարապետության դեմ։Նրա ջատագովները, այդ թվում՝ Բրունո Տաուտը, Հանս Պոլցիգը, Ֆրից Հոգերը և Էրիխ Մենդելսոնը, ցանկանում էին ստեղծել բանաստեղծական, արտահայտիչ և լավատեսական ճարտարապետություն։Շատ էքսպրեսիոնիստ ճարտարապետներ մասնակցել էին Առաջին համաշխարհային պատերազմին, և նրանց փորձառությունները, զուգորդված քաղաքական ցնցումների և սոցիալական ցնցումների հետ, որոնք հաջորդեցին 1919 թվականի գերմանական հեղափոխությանը, հանգեցրին ուտոպիստական հայացքի և ռոմանտիկ սոցիալիստական օրակարգի[16]: Տնտեսական պայմանները խստորեն սահմանափակեցին 1914-ից մինչև 1920-ականների կեսերը, կառուցված հանձնաժողովների թիվը[17] , ինչի արդյունքում ամենանորարար էքսպրեսիոնիստական նախագծերից շատերը, ներառյալ Բրունո Տաուտի Ալպիական ճարտարապետությունը և Հերման Ֆինստերլինի Ֆորմսպիլները, մնացին թղթի վրա: Թատրոնի և կինոյի տեսագրությունը ևս մեկ ելք ստեղծեց էքսպրեսիոնիստական երևակայության համար և լրացուցիչ եկամուտ ապահովեց դիզայներների համար[18] , ովքեր փորձում էին վիճարկել կոնվենցիաները կոշտ տնտեսական պայմաններում: Որոշակի տեսակ, որն օգտագործում է աղյուսներ իր ձևերը ստեղծելու համար (ոչ թե կոնկրետ), հայտնի է որպես Աղյուսի էքսպրեսիոնիզմ:

Էրիխ Մենդելսոնը (ով չէր սիրում էքսպրեսիոնիզմ տերմինը իր աշխատանքի համար)սկսեց իր կարիերան՝ նախագծելով եկեղեցիներ, սիլոսներ? և գործարաններ, որոնք մեծ երևակայություն էին պարունակում, բայց ռեսուրսների բացակայության պատճառով երբեք չկառուցվեցին: 1920 թվականին նա վերջապես կարողացավ կառուցել իր գործերից մեկը Պոտսդամ քաղաքում. աստղադիտարան և հետազոտական կենտրոն, որը կոչվում է Էյնշտեյն, որն անվանվել է ի պատիվ Ալբերտ Էյնշտայնի:Այն պետք է կառուցվեր երկաթբետոնից, սակայն տեխնիկական խնդիրների պատճառով վերջապես կառուցվեց ավանդական նյութերից պատված սվաղով։Նրա քանդակագործական ձևը, որը շատ տարբերվում էր Բաուհաուսի ուղղանկյուն ձևերից, նրան առաջին անգամ հանձնարարվեց կառուցել կինոթատրոններ և մանրածախ խանութներ Շտուտգարտում, Նյուրնբերգում և Բեռլինում: Նրա Մասհաուսը Բեռլինում եղել է ժամանակակից ոճի վաղ մոդելը:Նրա Կոլումբուշաուսը Բեռլինի Պոտսդամեր հրապարակում (1931թ.) նախատիպ էր հաջորդող մոդեռնիստական գրասենյակային շենքերի համար: (Այն քանդվել է 1957թ.-ին, քանի որ կանգնած էր Արևելյան և Արևմտյան Բեռլինների միջև ընկած գոտում, որտեղ կառուցվել էր Բեռլինի պատը):Նացիստների իշխանության գալուց հետո նա տեղափոխվեց Անգլիա (1933), այնուհետև ԱՄՆ (1941)[4]:

Ֆրից Հոգերը ժամանակաշրջանի մեկ այլ նշանավոր էքսպրեսիոնիստ ճարտարապետ էր: Նրա Չեխրհաուսը կառուցվել է որպես նավափոխադրող ընկերության կենտրոնակայանը և կառուցվել է հսկա շոգենավի օրինակով, եռանկյունաձև շինություն՝ սուր աղեղով:Այն կառուցվել է մուգ աղյուսից և օգտագործել է արտաքին հենարաններ՝ արտահայտելու իր ուղղահայաց կառուցվածքը։ Նրա արտաքին հարդարանքը փոխառված է գոթական տաճարներից, ինչպես նաև ներքին նկարները?: Հանս Պոլցիգը մեկ այլ նշանավոր էքսպրեսիոնիստ ճարտարապետներից էր: 1919 թվականին նա կառուցեց Գղոս Շահուսբիլհուսը, հսկայական թատրոն Բեռլինում, որը հինգ հազար հանդիսատես էր տեղավորում թատրոնի իմպրեսարիո Մաքս Ռայնհարդտի համար: Այն իր հսկա գմբեթից կախված երկարավուն ձևեր ուներ իր ճեմասրահում գտնվող հսկայական սյուների վրա: Նա նաև կառուցեց ԻՋ Ֆարբեն շենքը՝ խոշոր կորպորատիվ շտաբ, որն այժմ Ֆրանկֆուրտի Գյոթեի համալսարանի գլխավոր մասնաշենքն է: Բրունո Տաուտը մասնագիտացած էր բանվոր դասակարգի բեռլինցիների համար լայնածավալ բնակարանային համալիրների կառուցման մեջ: Նա կառուցել է տասներկու հազար անհատական միավորներ, երբեմն անսովոր ձևերով շենքերում, ինչպիսին է հսկա պայտը: Ի տարբերություն շատ այլ մոդեռնիստների, նա օգտագործում էր արտաքին վառ գույներ՝ իր շենքերին ավելի կյանք հաղորդելու համար[3]:

Ավստրիացի փիլիսոփա, ճարտարապետ և հասարակական քննադատ Ռուդոլֆ Շտայները նույնպես հնարավորինս հեռացավ ավանդական ճարտարապետական ձևերից:Նրա Երկրորդ Գյոթեանը, որը կառուցվել է 1926 թվականից Շվեյցարիայի Բազելի մոտակայքում, Էյնշտեյնտուրմը Պոտսդամում, Գերմանիա, և Երկրորդ Գյոթեանը, որը հեղինակել է Ռուդոլֆ Շտայները (1926 թ.), հիմնված չեն եղել ավանդական մոդելների վրա և ունեին ամբողջովին ինքնատիպ ձևեր:

Կառուցողական ճարտարապետություն (1919–1931)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

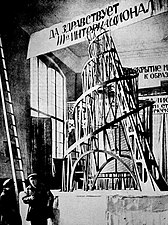

(1919)Աշտարակի մոդելը երրորդ միջազգային, Վլադիմիր Տատլին

-

Լենինի դամբարանը Մոսկվայում, Ալեքսեյ Շչուսև (1924)

-

ԽՍՀՄ տաղավարը 1925 թվականի Փարիզի դեկորատիվ արվեստի ցուցահանդեսոմ, Կոնստանտին Մելնիկով

-

Ռուսակովի բանվորական ակումբ, Մոսկվա, Կոնստանտին Մելնիկով (1928)

-

Բացօթյա դպրոց Ամստերդամում Յան Դյուկեր (1929–1930)

1917 թվականի ռուսական հեղափոխությունից հետո ռուս ավանգարդ նկարիչները և ճարտարապետները սկսեցին փնտրել նոր խորհրդային ոճ, որը կարող էր փոխարինել ավանդական նեոկլասիցիզմին: Նոր ճարտարապետական շարժումները սերտորեն կապված էին ժամանակաշրջանի գրական և գեղարվեստական շարժումների, բանաստեղծ Վլադիմիր Մայակովսկու ֆուտուրիզմի, նկարիչ Կասիմիր Մալևիչի սուպրեմատիզմի և նկարիչ Միխայիլ Լարիոնովի գունեղ ռայոնիզմի հետ?։ Ամենաապշեցուցիչ ձևավորումը, որ ի հայտ եկավ, աշտարակն էր, որն առաջարկել էր նկարիչ և քանդակագործ Վլադիմիր Տատլինը 1920 թվականին Երրորդ կոմունիստական ինտերնացիոնալի մոսկովյան հանդիպման համար. նա առաջարկեց չորս հարյուր մետր բարձրությամբ մետաղական երկու միահյուսված աշտարակ՝ մալուխներից? կախված չորս երկրաչափական ծավալներով:Ռուսական կառուցողական ճարտարապետության շարժումը սկսվել է 1921 թվականին մի խումբ արվեստագետների կողմից՝ Ալեքսանդր Ռոդչենկոյի գլխավորությամբ:Նրանց մանիֆեստում հայտարարվում էր, որ իրենց նպատակն է գտնել «նյութական կառույցների կոմունիստական արտահայտությունը»։Խորհրդային ճարտարապետները սկսեցին կառուցել բանվորական ակումբներ, կոմունալ բնակելի տներ և կոմունալ խոհանոցներ՝ ամբողջ թաղամասերը կերակրելու համար[4]:

Մոսկվայում հայտնված առաջին նշանավոր կառուցողական ճարտարապետներից մեկը Կոնստանտին Մելնիկովն էր, աշխատանքային ակումբների թիվը, այդ թվում՝ Ռուսակովի բանվորական ակումբը (1928թ.) և նրա սեփական տունը՝ Մելնիկովի տունը (1929թ.)գտնվում էր Մոսկվայի Արբատ փողոցում: Մելնիկովը մեկնեց Փարիզ 1925 թվականին, որտեղ կառուցեց խորհրդային տաղավարը 1925 թվականին Փարիզում Մոդեռն դեկորատիվ և արդյունաբերական արվեստի միջազգային ցուցահանդեսի համար, դա ապակուց և պողպատից պատրաստված բարձր երկրաչափական ուղղահայաց շինություն էր, որը հատվում էր անկյունագծով սանդուղքով և թագով մուրճով և մանգաղով: Կոնստրուկտիվիստ ճարտարապետների առաջատար խումբը՝ Վեսնին եղբայրների և Մոիսեյ Գինցբուրգի գլխավորությամբ, հրատարակում էր «Մոդեռն ճարտարապետություն» ամսագիրը։ Այս խումբը ստեղծեց մի քանի խոշոր կառուցողական նախագծեր Առաջին հնգամյա պլանի հետևանքով, ներառյալ վիթխարի Դնեպրի հիդրոէլեկտրակայանը (1932 թ.) և փորձ արեց սկսել բնակելի բլոկների ստանդարտացումը Գինցբուրգի Նարկոմֆինի շենքով: Կառուցողական ոճով են զբաղվել նաև նախասովետական շրջանի մի շարք ճարտարապետներ։ Ամենահայտնի օրինակը Լենինի դամբարանն էր Մոսկվայում (1924), Ալեքսեյ Շչուսևի (1924 թ.)[19]:

Կառուցողական ճարտարապետության հիմնական կենտրոններն էին Մոսկվան և Լենինգրադը:Այնուամենայնիվ, ինդուստրացման ընթացքում բազմաթիվ կառուցողական շենքեր կառուցվեցին գավառական քաղաքներում: Տարածաշրջանային արդյունաբերական կենտրոնները, ներառյալ Եկատերինբուրգը, Խարկովը կամ Իվանովոն, վերակառուցվել են կառուցողական ձևով. որոշ քաղաքներ, ինչպիսիք են Մագնիտոգորսկը կամ Զապորոժժիան, կառուցվել են նորովի (այսպես կոչված սոկգորոդ կամ «սոցիալիստական քաղաք»):

Ոճը 1930-ականներին զգալիորեն ընկավ բարեհաճությունից, փոխարինվեց ավելի մեծ ազգայնական ոճերով, որոնց օգտին էր Ստալինը: Կառուցողական ճարտարապետները և նույնիսկ Լե Կորբյուզիեի նախագծերը Խորհրդային Միության նոր պալատի համար 1931-1933 թվականներին, սակայն հաղթողը վաղ Ստալինյան շենքն էր, որը կոչվում էր հետկոնստրուկտիվիզմ?: Ռուսական վերջին խոշոր կառուցողական շենքը, Բորիս Իոֆանի կողմից, կառուցվել է Փարիզի համաշխարհային ցուցահանդեսի համար (1937 թ.), որտեղ այն կանգնած էր Հիտլերի ճարտարապետ Ալբերտ Շպեերի կողմից ֆաշիստական Գերմանիայի տաղավարին [20]:

Մոդեռնիզմը դառնում է շարժում (1928)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

1920-ականների վերջին մոդեռնիզմը դարձավ կարևոր շարժում Եվրոպայում։ Ճարտարապետությունը, որը նախկինում հիմնականում ազգային էր, սկսեց դառնալ միջազգային: Ճարտարապետները ճանապարհորդեցին, հանդիպեցին միմյանց և կիսվեցին մտքերով: Մի քանի մոդեռնիստներ, այդ թվում՝ Լե Կորբյուզիեն, մասնակցել են Ազգերի լիգայի շտաբի մրցույթին 1927 թվականին: Նույն թվականին գերմանական Վերկբւնդը ճարտարապետական ցուցահանդես կազմակերպեց Շտուտգարտում: Եվրոպայի տասնյոթ առաջատար մոդեռնիստ ճարտարապետներ հրավիրվեցին քսանմեկ տուն նախագծելու համար. Լե Կորբյուզիեն և Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոեն մեծ դեր խաղացին։1927 թվականին Լե Կորբյուզիեն, Պիեռ Շարոն և այլոք առաջարկեցին միջազգային կոնֆերանսի հիմնադրումը՝ ընդհանուր ոճի հիմքերը ստեղծելու համար։ Մոդեռն ճարտարապետների միջազգային կոնգրեսների (CIAM) առաջին հանդիպումը տեղի ունեցավ Շվեյցարիայի Լեման լճի դղյակում 1928թ. , Պիեռ Շարոն և Թոնի Գարնիերը Ֆրանսիայից Վիկտոր Բուրժուա Բելգիայից Վալտեր Գրոպիուսը, Էրիխ Մենդելսոնը, Էռնստ Մեյը և Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոեն Գերմանիայից; Յոզեֆ Ֆրանկ Ավստրիայից Մարտ Ստամը և Գերիտ Ռիթվելդը Նիդերլանդներից, Ադոլֆ Լոսը Չեխոսլովակիայից: Խորհրդային ճարտարապետների պատվիրակությունը հրավիրվել էր մասնակցելու, սակայն նրանք չկարողացան վիզա ստանալ: Հետագայում անդամներն էին իսպանացի Խոսեպ Լլուիս Սերտը և Ֆինլանդիայից Ալվար Ալտոն: Միացյալ Նահանգներից ոչ ոք չի մասնակցել: Երկրորդ հանդիպումը կազմակերպվել է 1930 թվականին Բրյուսելում Վիկտոր Բուրժուայի կողմից «Ռացիոնալ մեթոդներ բնակավայրերի խմբերի համար» թեմայով։ Երրորդ հանդիպումը՝ «Ֆունկցիոնալ քաղաքը» թեմայով, նախատեսված էր 1932 թվականին Մոսկվայում, սակայն վերջին պահին չեղարկվեց: Փոխարենը, պատվիրակներն իրենց հանդիպումն անցկացրին Մարսելի և Աթենքի միջև ճամփորդող զբոսաշրջային նավի վրա։ Նավի վրա նրանք միասին մշակեցին տեքստ, թե ինչպես պետք է կազմակերպվեն ժամանակակից քաղաքները: Տեքստը, որը կոչվում է «Աթենքի խարտիա», Կորբյուզիեի և մյուսների կողմից զգալի խմբագրումներից հետո, վերջապես հրապարակվեց 1957 թվականին և դարձավ ազդեցիկ տեքստ 1950-ական և 1960-ական թվականների քաղաքային պլանավորողների համար: Խումբը ևս մեկ անգամ հանդիպեց Փարիզում 1937 թվականին՝ քննարկելու հանրային բնակարանների հարցը, և նախատեսվում էր հանդիպել Միացյալ Նահանգներում 1939 թվականին, սակայն հանդիպումը չեղարկվեց պատերազմի պատճառով: Ժառանգությունը մոտավորապես ընդհանուր ոճ և վարդապետություն էր, որն օգնեց որոշել ժամանակակից ճարտարապետությունը Եվրոպայում և Միացյալ Նահանգներում Երկրորդ համաշխարհային պատերազմից հետո[4]:

Արտ Դեկո[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Գելրիս Լաֆիեթ հանրախանութի տաղավարը Փարիզի դեկորատիվ արվեստի միջազգային ցուցահանդեսում (1925)

-

Լա Սամարիտեին հանրախանութ, Անրի Սովաժ, Փարիզ, (1925–28)

Aրտ Դեկո ճարտարապետական ոճը (Ֆրանսիայում կոչվում է Սթայլ Մոդեղն), ժամանակակից էր, բայց այն մոդեռնիստական չէր. այն ուներ մոդեռնիզմի բազմաթիվ առանձնահատկություններ, ներառյալ երկաթբետոնի, ապակու, պողպատի, քրոմի օգտագործումը և մերժում էր ավանդական պատմական մոդելները, ինչպիսիք են Բոուզ-Արտ ոճը և նեոկլասիցիզմը, բայց, ի տարբերություն Լե Կորբյուզիեի և Միես վան դեր Ռոեի մոդեռնիստական ոճերի, այն շռայլորեն օգտագործում էր դեկորացիա և գույն:Այն զվարճանում էր արդիականության խորհրդանիշներով. կայծակներ, արևածագներ և զիգզագներ։ Արտ-Դեկոն սկսվել է Ֆրանսիայում մինչև Առաջին համաշխարհային պատերազմը և տարածվել ամբողջ Եվրոպայում: 1920-ականներին և 1930-ականներին այն դարձավ շատ տարածված ոճ ԱՄՆ-ում, Հարավային Ամերիկայում, Հնդկաստանում, Չինաստանում, Ավստրալիայում և Ճապոնիայում: Եվրոպայում Արտ-Դեկոն հատկապես հայտնի էր հանրախանութների և կինոթատրոնների համար: Ոճը իր գագաթնակետին հասավ Եվրոպայում 1925 թվականին Մոդեռն դեկորատիվ և արդյունաբերական արվեստի միջազգային ցուցահանդեսում, որտեղ ներկայացված էին Արտ-դեկո տաղավարներ և դեկորացիաներ քսան երկրներից: Միայն երկու տաղավարներ էին զուտ մոդեռնիստական. Լէ Քողբուսիեղի Էսպրիտ Նովոի տաղավարը, որը ներկայացնում էր նրա գաղափարը զանգվածային արտադրության բնակարանային միավորի մասին, և ԽՍՀՄ-ի տաղավարը Կոնստանտին Մելնիկովի կողմից շքեղ ֆուտուրիստական ոճով[21]:

Ավելի ուշ ֆրանսիական տեսարժան վայրերը Արտ Դեկո ոճով ներառում էին Գրենդ Ռեքս կինոթատրոնը Փարիզում, Լա Սամարիտեյն հանրախանութը Անրի Սովաժի (1926–28) և Սոցիալական և տնտեսական խորհրդի շենքը Փարիզում (1937–38) Օգյուստ Պերեի կողմից և պալատը։ Դե Տոկիոն և Շայլոյի Պալատը, որոնք երկուսն էլ կառուցվել են ճարտարապետների կոլեկտիվների կողմից 1937 թվականին Փարիզի Արվեստների և տեխնիկայի միջազգային ցուցահանդեսի համար[22]:

Ամերիկյան արվեստ, երկնաքերի ոճը (1919–1939)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Ռեյմոնդ Հուդի Ամերիկյան ռադիատորի շենքը Նյու Յորքում (1924)

-

Գուարդյան շինություն Դետրոիդում Վիրտ Գ. կողմից (1927–29)

-

Քրիսլեր շինություն Նյու Յորքում, Ուիլյամ Վան Ալեն (1928–30)

-

Քրոուն օֆ դը ջեներալ էլեքտրիկ բիլդինգ (նաև հայտնի է որպես 570 լեքսինգտոն ) Քրոսի կողմից (1933)

-

30 Ռոքֆելլեր կենտրոն, այժմ Քոմքաստ շենք, Ռոմին Հուդ (1933)

1920-ականների վերջին և 1930-ականների սկզբին Արտ Դեկոի ամերիկյան շքեղ տարբերակ հայտնվեց Քրայսլեր շենքում, Էմպայեր ստեյթում և Ռոքֆելլեր կենտրոնում Նյու Յորքում և Գոեարդիանում Դեթրոյթում: Չիկագոյի և Նյու Յորքի առաջին երկնաքերերը նախագծված էին նեոգոթիկ կամ նեոկլասիկական ոճով, սակայն այդ շենքերը շատ տարբեր էին: Նրանք համատեղել են ժամանակակից նյութերն ու տեխնոլոգիաները (չժանգոտվող պողպատ, բետոն, ալյումին, քրոմապատ պողպատ) Art Deco երկրաչափության հետ, ոճավորված զիգ-զագեր, կայծակներ, շատրվաններ, արևածագներ, իսկ Քրայսլերի շենքի վերնամասում՝ Art Deco «գարգոյլներ»՝ չժանգոտվող պողպատից ռադիատորի զարդանախշերի տեսքով: Այս նոր շենքերի ինտերիերը, որոնք երբեմն կոչվում են առևտրի տաճարներ», շքեղորեն զարդարված էին վառ հակապատկեր գույներով, երկրաչափական նախշերով, որոնք տարբեր կերպ են ազդել եգիպտական և մայաների բուրգերի, աֆրիկյան տեքստիլ նախշերի և եվրոպական տաճարների վրա։1924 թվականի Լոս Անջելեսի բետոնե խորանարդի վրա հիմնված Էննիս Հաուսում: Ոճը հայտնվեց 1920-ականների վերջին և 1930-ականներին ամերիկյան բոլոր խոշոր քաղաքներում: Ոճն առավել հաճախ օգտագործվում էր գրասենյակային շենքերում, բայց այն նաև հայտնվեց հսկայական կինոպալատներում, որոնք կառուցված խոշոր քաղաքներում, երբ ներկայացվեցին ձայնային ֆիլմերը:[23]

Հեշտացնել ոճը և հանրային աշխատանքների կառավարումը (1933–1939)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

ՀամաԽաղաղօվկիանոսյան դահլիճ Լոս Անջելեսում (1936)

-

Սան Ֆրանցիսկոյի ծովային թանգարանը, ի սկզբանե եղել է հանրային բաղնիք (1936 թ.)

-

Հուվեր ամբարտակի ընդունման աշտարակներ (1931–36)

-

Լոնգ Բիչի գլխավոր փոստային բաժանմունք (1933–34)

1929 թվականին Մեծ դեպրեսիայի սկիզբը վերջ դրեց շքեղ ձևավորված Արտ Դեկո ճարտարապետությանը և ժամանակավոր դադարեցրեց նոր երկնաքերերի կառուցումը:Այն նաև բերեց նոր ոճ, որը կոչվում է «Սթրիմլայն մոդերն» կամ երբեմն պարզապես Սթրիմլայն: Այս ոճը, որը երբեմն մոդելավորվում էր օվկիանոսային նավակների տեսքով, պարունակում էր կլորացված անկյուններ, ուժեղ հորիզոնական գծեր և հաճախ ծովային առանձնահատկություններ, ինչպիսիք են վերնաշենքերը և պողպատե վանդակապատերը:Այն կապված էր արդիականության և հատկապես տրանսպորտի հետ, ոճը հաճախ օգտագործվում էր նոր օդանավակայանի տերմինալների, երկաթուղային և ավտոբուսային կայանների, ինչպես նաև բենզալցակայանների և ճաշարանների համար, որոնք կառուցված էին աճող ամերիկյան մայրուղային համակարգի երկայնքով: 1930-ականներին ոճը օգտագործվում էր ոչ միայն շենքերում, այլև երկաթուղային լոկոմոտիվներում, նույնիսկ սառնարաններում և փոշեկուլներում: Այն և՛ փոխառել է արդյունաբերական դիզայնից, և՛ ազդել է դրա վրա[24]:

Միացյալ Նահանգներում Մեծ դեպրեսիան հանգեցրեց նոր ոճի կառավարական շենքերի համար, որը երբեմն կոչվում է PWA Moderne, Հանրային աշխատանքների ադմինիստրացիայի համար, որը սկսեց հսկա շինարարական ծրագրեր ԱՄՆ-ում՝ խթանելու զբաղվածությունը:Այն, ըստ էության, դասական ճարտարապետություն էր՝ զարդանախշերից զերծ և օգտագործվում էր նահանգային և դաշնային շենքերում՝ փոստային բաժանմունքներից մինչև այդ ժամանակների աշխարհի ամենամեծ գրասենյակային շենքը՝ Պենտագոնը (1941–43), որը սկսվել էր Միացյալ Նահանգների Երկրորդ աշխարհամարտից մտնելուց անմիջապես առաջ[25]:

Ամերիկյան մոդեռնիզմ (1919–1939)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Էնիսի տունը Լոս Անջելեսում, Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթ (1924)

-

Ֆլինգվոտեր՝ Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթ (1928–34)

-

Լովել Հելֆ հաուս Լոս Ֆելիզում, Լոս Անջելես, Կալիֆորնիա, Ռիչարդ Նեյտրայի կողմից (1927–29)

1920-1930-ական թվականներին Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթը վճռականորեն հրաժարվեց իրեն կապել ճարտարապետական որևէ շարժման հետ: Նա իր ճարտարապետությունը համարում էր ամբողջովին եզակի և իրենը:1916-ից 1922 թվականներին նա հեռացավ իր նախկին տափաստանային ոճից և փոխարենը աշխատեց ցեմենտով պատվաց տների վրա, սա հայտնի դարձավ որպես նրա «մայաների ոճ»՝ հին մայաների քաղաքակրթության բուրգերից հետո: Նա որոշ ժամանակ փորձեր կատարեց մասսայական արտադրության մոդուլային բնակարանների հետ: Նա իր ճարտարապետությունը նույնացնում էր որպես «Ուսոնյան»՝ ԱՄՆ-ի, «ուտոպիստական» և «օրգանական սոցիալական կարգի» համադրություն։ Նրա բիզնեսը մեծ ազդեցություն ունեցավ 1929 թվականին սկսված Մեծ դեպրեսիայի սկզբից. նա ուներ ավելի քիչ հարուստ հաճախորդներ, ովքեր ցանկանում էին փորձարկել: 1928-ից 1935 թվականներին նա կառուցեց ընդամենը երկու շենք՝ հյուրանոց Արիզոնայի Չանդլերի մոտ, և նրա բոլոր բնակավայրերից ամենահայտնին՝ Ֆալինգուոթերը (1934–37), Փենսիլվանիայում հանգստյան տուն Էդգար Ջ. Կաուֆմանի համար[4]:

Ավստրիացի ճարտարապետ Ռուդոլֆ Շինդլերը նախագծել է այն, ինչ կարելի է անվանել առաջին տունը ժամանակակից ոճով 1922 թվականին՝ Շինդլերի տունը։ Շինդլերը նաև նպաստեց ամերիկյան մոդեռնիզմին Նյուպորտ Բիչում գտնվող Լովել բիչ հաուսի համար իր դիզայնով: Ավստրիացի ճարտարապետ Ռիչարդ Նեյտրան տեղափոխվեց Միացյալ Նահանգներ 1923 թվականին, կարճ ժամանակ աշխատեց Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթի հետ, ինչպես նաև արագ դարձավ ամերիկյան ճարտարապետության ուժը իր մոդեռնիստական դիզայնի միջոցով նույն հաճախորդի՝ Լոս Անջելեսի Լովել Հելֆ Հաուսի համար: Նեյտրայի ամենաուշագրավ ճարտարապետական աշխատանքը 1946 թվականին Կաուֆման Անապատի Տունն էր, և նա նախագծեց հարյուրավոր հետագա նախագծեր[26]:

1937 թվականի Փարիզի միջազգային ցուցահանդեսը և բռնակալների ճարտարապետությունը[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Լուի-Իպոլիտ Բուլեոյի, Ժակ Կառլուի և Լեոն Ազեմայի «Պելե Դու Շայոը» 1937 թվականի Փարիզի միջազգային ցուցահանդեսից

-

Նացիստական Գերմանիայի տաղավարը (ձախից) 1937 թվականի Փարիզի ցուցահանդեսում կանգնած էր Ստալինի Խորհրդային Միության տաղավարին (աջից):

-

Իսպանական Երկրորդ Հանրապետության տաղավարի վերակառուցումը Խոսեպ Լուիս Սերտի կողմից (1937 թ.) ցուցադրված է Պիկասոյի «Գերնիկա» կտավը (1937 թ.)

-

Զեպելինֆերդ մարզադաշտը Նյուրնբերգում, Գերմանիա (1934), որը կառուցվել է Ալբերտ Շպեերի կողմից նացիստական կուսակցության հանրահավաքների համար

-

Ֆաշիզմի տուն Կոմո, Իտալիա, Ջուզեպպե Տերրագնի (1932–1936)

1937 թվականի Փարիզի միջազգային ցուցահանդեսը Փարիզում փաստորեն նշանավորեց Արտ Դեկոի և նախապատերազմյան ճարտարապետական ոճերի ավարտը: Տաղավարների մեծ մասը նեոկլասիկական դեկո ոճով էր՝ սյունաշարերով և քանդակագործական դեկորացիաներով։ Նացիստական Գերմանիայի տաղավարները, նախագծված Ալբերտ Շպեերի կողմից, գերմանական նեոկլասիկական ոճով, արծիվով և սվաստիկայով, կանգնած էին Խորհրդային Միության տաղավարի վրա, որի վրա պատկերված էին բանվորի և գյուղացու հսկայական արձանները, որոնք կրում էին մուրճն ու մանգաղը: Ինչ վերաբերում է մոդեռնիստներին, ապա Լե Կորբյուզեն գործնականում, բայց ոչ այնքան անտեսանելի էր ցուցահանդեսում. նա մասնակցել է Պավիոն Դե տոն նուվոին, բայց հիմնականում կենտրոնացել է իր նկարչության վրա[27] : Մի մոդեռնիստ, ով իսկապես ուշադրություն գրավեց, Լե Կորբյուզիեի՝ իսպանացի ճարտարապետ Խոսեպ Լյուիս Սերտի համագործակիցն էր, որի Երկրորդ Իսպանիայի Հանրապետության տաղավարը մաքուր մոդեռնիստական ապակի և պողպատե տուփ էր: Ներսում ցուցադրված էր Ցուցադրության ամենամոդեռնիստական աշխատանքը՝ Պաբլո Պիկասոի «Գերնիկա» կտավը։

1930-ական թվականներին ազգայնականության վերելքն արտացոլվել է Իտալիայի ֆաշիստական ճարտարապետության մեջ, իսկ Գերմանիայի նացիստական ճարտարապետությունը՝ հիմնված դասական ոճերի վրա և նախատեսված է արտահայտելու ուժ և վեհություն: Նացիստական ճարտարապետությունը, որի մեծ մասը նախագծվել է Ալբերտ Շպերի կողմից, նպատակ ուներ հանդիսատեսին հիացնել իր հսկայական մասշտաբով: Ադոլֆ Հիտլերը մտադիր էր Բեռլինը դարձնել Եվրոպայի մայրաքաղաք՝ ավելի մեծ, քան Հռոմը կամ Փարիզը։ Նացիստները փակեցին Բաուհաուսը, և ամենահայտնի ժամանակակից ճարտարապետները շուտով մեկնեցին Բրիտանիա կամ Միացյալ Նահանգներ: Իտալիայում Բենիտո Մուսոլինին ցանկացել է ներկայանալ որպես Հին Հռոմի փառքի ու կայսրության ժառանգորդ[28]: Մուսոլինիի կառավարությունն այնքան թշնամական չէր մոդեռնիզմի նկատմամբ, որքան նացիստները. 1920-ականների իտալական ռացիոնալիզմի ոգին շարունակվեց՝ ճարտարապետ Ջուզեպպե Տերրագնիի աշխատանքով։Նրա Կասա Դե Ֆանսիոն Կոմոում, տեղական ֆաշիստական կուսակցության շտաբ-բնակարանը, կատարյալ մոդեռնիստական շենք էր՝ երկրաչափական համամասնություններով (33,2 մետր երկարությամբ և 16,6 մետր բարձրությամբ), մաքուր մարմարից պատրաստված ճակատով և Վերածննդի ոգեշնչված ներքին բակով: Տերրագնին հակառակ էր Մարչելլո Պյաչիտինին՝ մոնումենտալ ֆաշիստական ճարտարապետության ջատագովը, ով վերակառուցեց Հռոմի համալսարանը և նախագծեց իտալական տաղավարը 1937 թվականին Փարիզի ցուցահանդեսում և ծրագրեց Հռոմի մեծ վերակառուցում ֆաշիստական մոդելով[4]:

Նյու Յորքի համաշխարհային ցուցահանդես (1939)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Տրիլոնը և Ծայրամասը՝ 1939 թվականի համաշխարհային ցուցահանդեսի խորհրդանիշները

-

Ֆորդ Մոդերն Քոմպնիի տաղավարը՝ Ստրիմլայն ոճով

-

ՌՑԱ տաղավարում ցուցադրվել են վաղ հանրային հեռուստատեսային հեռարձակումներ

-

Ապակե տան հյուրասենյակը, որը ցույց է տալիս, թե ինչպիսի տեսք կունենան ապագա տները

1939 թվականի Նյու Յորքի համաշխարհային տոնավաճառը ճարտարապետության մեջ շրջադարձային կետ դրեց Արտ Դեքոի և ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության միջև: Տոնավաճառի թեման Վաղվա աշխարհն էր, և դրա խորհրդանիշներն էին զուտ երկրաչափական տրիլոնը և ծայրամասային քանդակը: Այն ուներ Art Deco-ի բազմաթիվ հուշարձաններ, օրինակ՝ Ֆորդ Պավլիոնը Ստրիմլայն մոդերն ոճով, բայց նաև ներառում էր նոր միջազգային ոճը, որը փոխարինելու էր Արտ Դեկոին՝ որպես պատերազմից հետո գերիշխող ոճ:Ֆինլանդիայի տաղավարները՝ Ալվար Ալտոյի, Շվեդիայի՝ Սվեն Մարկելիուսի և Բրազիլիայի՝ Օսկար Նիմեյերի և Լուսիո Կոստայի տաղավարները, անհամբերությամբ սպասում էին նոր ոճին:Նրանք դարձան հետպատերազմյան մոդեռնիստական շարժման առաջնորդներ[4]:

Երկրորդ համաշխարհային պատերազմ, պատերազմական նորարարություն և հետպատերազմյան վերակառուցում (1939–1945)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Հավրի կենտրոնը ավերվել է ռմբակոծությունից 1944 թ

-

Լը Հավրի կենտրոնը, որը վերակառուցվել է Օգյուստ Պեռեի կողմից (1946–1964)

-

Քուոնսեթ խրճիթ դեպի Ճապոնիա (1945)

Երկրորդ համաշխարհային պատերազմը (1939–1945) և դրա հետևանքները հիմնական գործոնն էին շինարարական տեխնոլոգիաների ոլորտում նորարարությունների խթանման և, իր հերթին, ճարտարապետական հնարավորությունների համար[25][29]: Պատերազմական արդյունաբերական պահանջները հանգեցրին պողպատի և այլ շինանյութերի պակասի, ինչը հանգեցրեց նոր նյութերի ընդունմանը, ինչպիսիք են ալյումինը: Պատերազմը և հետպատերազմյան ժամանակաշրջանը բերեցին հավաքովի շինությունների օգտագործման մեծ ընդլայնում, հիմնականում զինվորականների և կառավարության համար: Առաջին աշխարհամարտի Նիսսեն մետաղական կիսաշրջանաձև խրճիթը վերածնվեց որպես Քուանսեթ խրճիթ: Պատերազմից անմիջապես հաջորդող տարիներին զարգացան ռադիկալ փորձարարական տներ, այդ թվում՝ էմալապատ պողպատե Լուստրոն տունը (1947–1950) և Բուճմիստեր Ֆուլլերի փորձնական ալյումինե Դումաքսիոն Հաուսը[29][30]:

Պատերազմի պատճառած աննախադեպ ավերածությունները ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության վերելքի ևս մեկ գործոն էին: Խոշոր քաղաքների մեծ հատվածներ՝ Բեռլինից, Տոկիոյից և Դրեզդենից մինչև Ռոտերդամ և արևելյան Լոնդոն, Ֆրանսիայի բոլոր նավահանգստային քաղաքները, մասնավորապես՝ Լը Հավրը, Բրեստը, Մարսելը, Շերբուրգը ավերվել են ռմբակոծության հետևանքով։ Միացյալ Նահանգներում 1920-ականներից ի վեր քիչ քաղաքացիական շինարարություն էր իրականացվել: Պատերազմից վերադարձած միլիոնավոր ամերիկացի զինվորների համար բնակարաններ էին անհրաժեշտ:Հետպատերազմյան բնակարանների պակասը Եվրոպայում և Միացյալ Նահանգներում հանգեցրեց կառավարության կողմից ֆինանսավորվող հսկայական բնակարանային ծրագրերի նախագծմանը և կառուցմանը, սովորաբար ամերիկյան քաղաքների քայքայված կենտրոնում և Փարիզի արվարձաններում և եվրոպական այլ քաղաքներում, որտեղ հող կար։

Ամենամեծ վերակառուցման ծրագրերից մեկը Լե Հավրի քաղաքի կենտրոնն էր, որը ավերվել էր գերմանացիների և դաշնակիցների ռմբակոծության հետևանքով 1944թ. Կենտրոնում 133 հեկտար շինություններ հարթվել են, ավերվել է 12500 շենք, 40000 մարդ մնացել է անօթևան: Ճարտարապետ Օգյուստ Պերեթը, երկաթբետոնի և հավաքովի նյութերի կիրառման մարտիկը, նախագծել և կառուցել է քաղաքի բոլորովին նոր կենտրոն՝ բազմաբնակարան շենքերով, մշակութային, առևտրային և կառավարական շենքերով:Նա հնարավորության դեպքում վերականգնեց պատմական հուշարձանները և կառուցեց նոր եկեղեցի՝ Սուրբ Ջոզեֆը, որի կենտրոնում փարոս հիշեցնող աշտարակ էր՝ հույս ներշնչելու համար: Նրա վերակառուցված քաղաքը 2005 թվականին հռչակվել է ՅՈՒՆԵՍԿՕ-ի համաշխարհային ժառանգության օբյեկտ[4]:

Լե Կորբյուզիեն և Սիտե Ռադիեուսը (1947–1952)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Ունիտե Հաբիտատիոնի օրիգինալ ստորաբաժանման սրահ և պատշգամբ, այժմ Փարիզի Սիտե դե լախշիտե էտ Պատխիմոնինում (1952 թ.)

-

Նոտր-Դամ-դու-Օ մատուռը Ռոնշամպում (1950-1955)

Պատերազմից անմիջապես հետո ֆրանսիացի ճարտարապետ Լե Կորբյուզիեն, ով մոտ վաթսուն տարեկան էր և տասը տարի շենք չէր կառուցել, Ֆրանսիայի կառավարությունը հանձնարարեց Մարսելում նոր բնակարան կառուցել: Նա այն անվանել է Ունիտե Հաբիտատիոն Մարսելում, բայց այն ավելի տարածված է անվանել «Պայծար քաղաք» (իսկ ավելի ուշ «Խենթի քաղաքը» Մարսելում ֆրանսերենով) ֆուտուրիստական քաղաքաշինության մասին գրքի անունից:Հետևելով նրա նախագծային վարդապետություններին, շենքն ուներ բետոնե շրջանակ, որը բարձրացված էր փողոցի վերևում՝ հենասյուների վրա: Այն պարունակում էր 337 դուպլեքս բնակարան, որոնք տեղավորվում էին շրջանակի մեջ, ինչպես փազլի կտորներ: Յուրաքանչյուր միավոր ուներ երկու մակարդակ և փոքրիկ պատշգամբ:Ներքին «փողոցները» ունեին խանութներ, մանկապարտեզ և այլ ծառայություններ, իսկ հարթ տեռասի տանիքը՝ վազքուղի, օդափոխման խողովակներ և փոքրիկ թատրոն։ Լե Կորբյուզիեն նախագծել է կահույք, գորգեր և լամպեր, որոնք համապատասխանում են շենքին, բոլորը զուտ ֆունկցիոնալ են. միակ զարդարանքը ինտերիերի գույների ընտրությունն էր, որը Լե Կորբյուզիեն նվիրեց բնակիչներին: Ունիտե Հաբիտատիոնը դարձավ նմանատիպ շենքերի նախատիպ այլ քաղաքներում, ինչպես Ֆրանսիայում, այնպես էլ Գերմանիայում: Համակցված Ռոնշամպի Նոտր-Դամ դյու-Օ մատուռի համար նրա նույնքան արմատական օրգանական ձևավորման հետ՝ այս աշխատանքը Կորբյուզեին առաջ մղեց հետպատերազմյան ժամանակակից ճարտարապետների առաջին շարքում[27]:

X թիմը և 1953 թվականի ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության միջազգային կոնգրեսը[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

1950-ականների սկզբին Միշել Էքոշարը, Մարոկկոյում Ֆրանսիայի հովանավորության տակ գտնվող քաղաքաշինության տնօրենը, պատվիրեց Գամման (Մարոկկոյի ժամանակակից ճարտարապետների խումբ), որը սկզբում ներառում էր ճարտարապետներ Էլի Ազագուրին, Ջորջ Քանդիլիսը, Ալեքսիս Յոսիկը և Շադրախ Վուդը, Կասաբլանկայի Հայ Մոհամմեդի թաղամասը, որը «մշակութային հատուկ կենդանի հյուսվածք» էր ապահովում գյուղացիների և գաղթականների համար[31]: Սեմիրամիս (Մեղրախորիսխ) և Կենտրոնական Կարիերան այս ժողովրդական մոդեռնիզմի առաջին օրինակներից էին[32]:

1953 թվականից գործում է Մոդեռն ճարտարապետության միջազգային կոնգրեսներում ԱԹԲԱԹ֊Աֆրիկա շինարարական արտադրամասի աֆրիկյան մասնաճյուղը, որը հիմնադրվել է 1947 թվականին մի խումբ ձեռներեցների կողմից, այդ թվում էին Լե Կորբյուզիեն, Վլադիմիր Բոդյանսին և Անդրե Վոգենսկին, որոնք պատրաստել են Կազաբլանկայի բիդոնվիլների ուսումնասիրություն՝ «Բնակչության ամենամեծ թվի համար» վերնագրով[33]: Հաղորդավարներ՝ Ժորժ Քանդիլիսը և Միշել Էկոչարդը, վիճում էին, դեմ էին այդ տեսությանը, քանի որ ճարտարապետներն իրենց նախագծերում պետք է հաշվի առնեն տեղական մշակույթը և կլիման[34][31][35]։ Սա մեծ բանավեճ առաջացրեց ամբողջ աշխարհի մոդեռնիստ ճարտարապետների միջև և, ի վերջո, հրահրեց հերետիկոսություն և 10-րդ թիմի ստեղծումը.[34][36][37]: Էկոչարդի 8×8 մետրով մոդելը Կենտրոնական կարիերայում նրան ճանաչեց որպես կոլեկտիվ բնակարանների ճարտարապետության առաջամարտիկի, չնայած նրա մարոկացի գործընկեր Էլի Ազագուրին քննադատում էր նրան համարելով որպես ծառայողական գործիք` ֆրանսիական գաղութային ռեժիմին և անտեսելու համար տնտեսական և սոցիալական անհրաժեշտություն, որ մարոկկացիներն ավելի բարձր բնակչության խտությամբ ապրում են ուղղահայաց բնակարաններում,[38][39][40]:

Ուշ մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ուշ մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետությունը սովորաբար ներառում է բացառություններով նախագծված շենքեր (1968–1980):Մոդեռնիստական ճարտարապետությունը ներառում է 1945-1960-ական թվականներին նախագծված շենքերը: Ուշ մոդեռնիստական ոճը բնութագրվում է համարձակ ձևերով և սուր անկյուններով, որոնք մի փոքր ավելի հստակ են, քան բրուտալիստական ճարտարապետությունը[41]:

Հետպատերազմյան մոդեռնիզմը Միացյալ Նահանգներում (1945–1985)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ճարտարապետության միջազգային ոճը հայտնվեց Եվրոպայում, մասնավորապես Բաուհաուս շարժման մեջ, 1920-ականների վերջին։1932 թվականին այն ճանաչվել և անվանվել է Նյու Յորքի Մոդեռն արվեստի թանգարանում կազմակերպված ցուցահանդեսում, որը կազմակերպել էին ճարտարապետ Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոնը և ճարտարապետ Հենրի-Ռասել Հիչքոկը, 1937-1941 թվականներին՝ Գերմանիայում Հիտլերի և նացիստների վերելքից հետո, Գերմանական Բաուհաուս շարժման առաջնորդներից շատերը նոր տուն գտան Միացյալ Նահանգներում և կարևոր դեր խաղացին ամերիկյան ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության զարգացման գործում:

Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթը և Գուգենհայմի թանգարանը[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթի Ֆլորիդայի հարավային քոլեջի Պֆայֆերի մատուռը

-

Ջոնսոն Վաքսի գլխավոր գրասենյակի և հետազոտական կենտրոնի աշտարակը (1944–50)

-

Դե Պրայս Թաուերը Բարտեսվիլում,Օկլահոմա(1956)

-

Սողոմոն Գուգենհայմի թանգարան, Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթ (1946–1959)

1947թ.Ֆրենկ Լլոյդ Ռայթը ութսուն տարեկան էր: Նա ներկա էր ամերիկյան մոդեռնիզմի սկզբում, և թեև հրաժարվեց ընդունել, որ ինքը պատկանում է որևէ շարժմանը, շարունակում էր առաջատար դեր խաղալ գրեթե մինչև վերջը: Նրա ամենաօրիգինալ վաղ նախագծերից մեկը Ֆլորիդայի Հարավային քոլեջի համալսարանն էր Լեյքլենդում, Ֆլորիդա, որը սկսվել է 1941 թվականին և ավարտվել 1943 թվականին:Նա նախագծել է ինը նոր շինություններ, որոնք անվանել է «Արևի զավակ»: Նա գրել է, որ ուզում է, որ համալսարանը «Արևի զավակը կառուցվի հողից ու լույսի մեջ?»։

1940-ականներին նա ավարտեց մի քանի նշանավոր նախագծեր, այդ թվում՝ Ջոնսն Վաքս Հեդքորթրսը և Փրայս Թավերը Բարթլսվիլում, Օկլահոմաում? (1956): Շենքն անսովոր է, քանի որ այն հենված է չորս վերելակների հորաններից բաղկացած կենտրոնական միջուկով.? Շենքի մնացած մասը մինչև այս միջուկը երեսպատված է, ինչպես ծառի ճյուղերը: Ռայթն ի սկզբանե նախագծել էր կառույցը Նյու Յորքում բնակելի շենքի համար: Այդ նախագիծը չեղարկվեց Մեծ դեպրեսիայի պատճառով, և նա հարմարեցրեց Օկլահոմայում նավթամուղի և սարքավորումների ընկերության դիզայնը: Նա գրել է, որ Նյու Յորքում իր շենքը կկորեր բարձր շենքերի անտառում, իսկ Օկլահոմայում այն մենակ էր։ Դիզայնը սիմետրիկ է?, յուրաքանչյուր կողմ տարբեր է:

1943 թվականին արվեստի հսկիչ ? Սոլոմոն Ռ. Գուգենհայմի կողմից նրան հանձնարարվել է նախագծել թանգարան իր ժամանակակից արվեստի հավաքածուի համար: Նրա դիզայնը լիովին օրիգինալ էր. թասաձև շինություն՝ ներսում պարուրաձև թեքահարթակով?, որը թանգարանի այցելուներին առաջնորդում էր դեպի վերընթաց շրջագայություն դեպի 20-րդ դարի արվեստ: Աշխատանքները սկսվել են 1946 թվականին, սակայն ավարտվել են միայն 1959 թվականին, երբ նա մահացել է [4]:

Վալտեր Գրոպիուս և Մարսել Բրոյեր[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Հարվարդի իրավաբանական դպրոցի պատմությունների սրահ Վալտեր Գրոպիուսի և (Ճարտարապետների համագործակցություն)

-

Դե Ստիլմեն Հաուս Լիչֆեիլդ, Կոնեկտիկուտ, Մարսել Բրոյերի կողմից (1950) Լողավազանի որմնանկարը Ալեքսանդր Կալդերի կողմից

-

ՊենԱմի շենքը (այժմ Մեթլաֆ շենքը) Նյու Յորքում, Վալտեր Գրոպիուսի և Ճարտարապետների համագործակցության կողմից (1958–63)

Վալտեր Գրոպիուսը՝ Բաուհաուզի հիմնադիրը, տեղափոխվեց Անգլիա 1934 թվականին և այնտեղ անցկացրեց երեք տարի, նախքան Հարվարդի Դիզայնի բարձրագույն դպրոցի Վալտեր Հադնութի կողմից Միացյալ Նահանգներ հրավիրվեց։ Գրոպիուսը դարձավ ճարտարապետության ֆակուլտետի ղեկավար։ Մարսել Բրոյերը, ով նրա հետ աշխատել էր Բաուհաուսում, միացավ նրան և գրասենյակ բացեց Քեմբրիջում: Գրոպիուսի և Բրեյերի համբավը գրավեց բազմաթիվ ուսանողների, որոնք իրենք դարձան հայտնի ճարտարապետներ, այդ թվում՝ Իեո Մինգ Պեյը և Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոնը։ Նրանք կարևոր հանձնաժողով չստացան մինչև 1941 թվականը, երբ նրանք նախագծեցին բնակարաններ աշխատողների համար Քենսինգթոնում, Փենսիլվանիա, Պիտսբուրգի մոտակայքում, 1945 թվականին Գրոպիուսը և Բրոյերը համագործակցեցին ավելի երիտասարդ ճարտարապետների խմբի հետ Ճարտարապետների համագործակցություն անունով: Նրանց նշանավոր աշխատանքները ներառում էին Հարվարդի դիզայնի բարձրագույն դպրոցի շենքը, Աթենքում ԱՄՆ դեսպանատունը (1956–57) և Պան Ամերիքան Էյերվեյսի կենտրոնակայանը Նյու Յորքում (1958–63)[4]:

Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոհե[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Վիլլա Թուգենհատ Բռնոյում, Չեխիա (1928–30)

-

Քրոուն Հոլլ Իլինոյսի տեխնոլոգիական ինստիտուտում, Չիկագո (1956)

-

Սիգրամ Բիլդինգ, Նյու Յորք, 1958, Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոհեի կողմից

Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոեն նկարագրել է իր ճարտարապետությունը հայտնի ասացվածքով՝ «Քիչը շատ է?»: Լինելով 1939-1956 թվականներին Իլինոյսի տեխնոլոգիական ինստիտուտի ճարտարապետության դպրոցի տնօրեն Միեսը (ինչպես նա սովորաբար հայտնի էր) Չիկագոն դարձրեց հետպատերազմյան տարիներին ամերիկյան մոդեռնիզմի առաջատար քաղաքը: Նա ինստիտուտի համար կառուցեց նոր շենքեր մոդեռնիստական ոճով, երկու բարձրահարկ բազմաբնակարան շենքեր Լեյքշոր Դրայվում (1948–51), որոնք մոդելներ դարձան բարձրահարկերի համար ողջ երկրում։ Մյուս հիմնական աշխատանքները ներառում էին Ֆարնսվորթ տունը Պլանոյում, Իլինոյս (1945–1951), պարզ հորիզոնական ապակե տուփ, որը հսկայական ազդեցություն ունեցավ ամերիկյան բնակելի ճարտարապետության վրա: Չիկագոյի կոնվենցիայի կենտրոնը (1952–54) և Քրաուվն Հոլը Իլինոյսի տեխնոլոգիական ինստիտուտում (1950–56) և «Սերգրամ Բիլդինգ»-ը Նյու Յորքում (1954–58) նույնպես սահմանեցին մաքրության և նրբագեղության նոր չափանիշ։ Գրանիտե սյուների հիման վրա հարթ ապակյա և պողպատե պատերին գույնի շունչ է տրվել կառուցվածքում բրոնզե տոնով? I-ճառագայթների կիրառմամբ: Նա վերադարձել է Գերմանիա 1962–68-ին՝ Բեռլինում նոր Ազգային պատկերասրահը կառուցելու համար։ Նրա աշակերտներն ու հետևորդները ներառում էին Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոնը և Էերո Սաարինենը, որոնց աշխատանքի վրա էականորեն ազդել են նրա գաղափարները[4]:

Ռիչարդ Նեյտրա և Չարլզ և Ռեյ Իմս[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Ռիչարդ Նեյտրայի, Նեյտրայի գրասենյակային շենքը Լոս Անջելեսում (1950)

-

Ռիչարդ Նեյտրայի Կոնստանս Պերկինսի տունը, Լոս Անջելես (1962)

ԱՄՆ-ում նոր ոճով բնակելի ազդեցիկ ճարտարապետներից էին Ռիչարդ Նեյտրան և Չարլզ և Ռեյ Իմսը: Իմսի ամենահայտնի գործն էր Էիմս Հաուսը Պասիֆիք Պալիսադեսում,Կալիֆորնիա, (1949) Չարլզ Իմսը համագործակցելով Էրո Սարինենի հետ: Այն բաղկացած է երկու կառույցներից՝ ճարտարապետների նստավայրից և նրա արվեստանոցից՝ միացված L-ի տեսքով: Ճապոնական ճարտարապետության ազդեցության տակ, պատրաստված է կիսաթափանցիկ և թափանցիկ վահանակներից, որոնք կազմակերպված են պարզ ծավալներով, հաճախ օգտագործելով բնական նյութեր՝ հենված պողպատե շրջանակի վրա: Տան շրջանակը տասնվեց ժամում հավաքել են հինգ բանվորներ։ Նա լուսավորեց իր շենքերը մաքուր գույների վահանակներով[4]:

Ռիչարդ Նեյտրան շարունակում էր ազդեցիկ տներ կառուցել Լոս Անջելեսում՝ օգտագործելով պարզ տուփի թեման: Այս տներից շատերը ջնջեցին ափսե ապակուց պատերով ներքին և արտաքին տարածքների միջև գծային տարբերությունը?[42]: Նուչրս Քոնտրենս Պերկինս Հաուսը Փասադենայում, Կալիֆոռնիա (1962) վերստուգում էր մի համեստ ընտանիքի բնակարանը: Այն կառուցվել է էժան նյութից՝ փայտից, գիպսից և ապակուց, և ավարտվել է ընդամենը 18,000 դոլար արժողությամբ: Նեյտրան տունը հասցրեց իր տիրոջ՝ փոքրիկ կնոջ ֆիզիկական չափերին: Այն ունի արտացոլող լողավազան, որը ոլորվում է տան ապակե պատերի տակ: Նեուտրաի ամենաարտասովոր շինություններից մեկը Կալիֆոռնիայի Գարդեն Գրովում գտնվող Շեֆերս Գրոուսն էր, որը պարունակում էր հարակից ավտոկայանատեղի, որտեղ հավատացյալները կարող էին հետևել ծառայությանը՝ առանց իրենց մեքենաները լքելու:

Սկիդմոր, Օինգս և Մերիլլ և Ուոլաս Ք. Հարիսոն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Արտադրողներ վստահություն ընկերության շինություն Սկիդմորի, Օիգսի և Մերիլի կողմից, Նյու Յորք քաղաք (1954)

-

Beinecke գրադարան Յեյլի համալսարանում Սկիդմոր, Օվինգս և Մերիլլի-ի կողմից

-

Միավորված ազգերի կազմակերպության կենտրոնակայանը Նյու Յորքում, Ուոլաս Հարիսոնի՝ Օսկար Նիմեյերի և Լե Կորբյուզիեի հետ (1952)

-

Մետրոպոլիտեն օպերային թատրոնը Նյու Յորքի Լինքոլն կենտրոնում, Ուոլաս Հարիսոնի (1966)

Հետպատերազմյան տարիներին նշանավոր ժամանակակից շենքերից շատերը արտադրվել են երկու ճարտարապետական մեգա գործակալությունների կողմից, որոնք համախմբել են դիզայներների մեծ թիմեր շատ բարդ նախագծերի համար: Սկիդմոր, Օինգս և Մերիլ ընկերությունը հիմնադրվել է Չիկագոյում 1936 թվականին Լուի Սկիդմորի և Նաթանիել Օուինգսի կողմից, իսկ 1939 թվականին միացել է ինժեներ Ջոն Մերիլը, այն շուտով անվանվել է ՍՕՄ: Նրա առաջին մեծ նախագիծը Օք Ռիջը Ազգային Լաբորատորիան էր Օք Ռիջում, Թենեսիում, հսկա պետական կայանքը, որը արտադրեց պլուտոնիում առաջին միջուկային զենքի համար?: 1964 թվականին ընկերությունն ուներ տասնութ «գործընկեր-սեփականատերեր», 54 «հարակից մասնակիցներ» և 750 ճարտարապետներ, տեխնիկներ, դիզայներներ, դեկորատորներ և լանդշաֆտային ճարտարապետներ։ Նրանց ոճը հիմնականում ոգեշնչված էր Լյուդվիգ Միս վան դեր Ռոեի աշխատանքով, և նրանց շենքերը շուտով մեծ տեղեր ունեցան Նյու Յորքի երկնքում, ներառյալ Մանհեթեն Հաուսը (1950–51), Լևեր Հաուսը (1951–52) և Արտադրողներ վստահության ընկերություն շինությունը (1954):Ավելի ուշ ընկերության շենքերը ներառում են Յեյլի համալսարանի Բեինեք գրադարանը (1963թ.), Ուիլիսի աշտարակը, նախկինում Չիկագոյում գտնվող Սիրս Թավերը (1973թ.) և Համար Մեկ Համաշխարհային Առևտրի Կենտրոնը Նյու Յորքում (2013թ.), որը փոխարինել է ահաբեկչության ժամանակ ավերված շենքը 11 սեպտեմբերի 2001 թ..[4]:

Ուոլաս Հարիսոնը մեծ դեր է խաղացել Նյու Յորքի ժամանակակից ճարտարապետական պատմության մեջ: Որպես Ռոքֆելլեր ընտանիքի ճարտարապետական խորհրդատու՝ նա օգնեց նախագծել Ռոքֆելլեր կենտրոնը, որը 1930-ականների գլխավոր Արտ Դեկո ճարտարապետական նախագիծն էր: Նա ղեկավարում էր 1939 թվականի Նյու Յորքի համաշխարհային ցուցահանդեսի ճարտարապետությունը ? և իր գործընկեր Մաքս Աբրամովիցի հետ ՄԱԿ-ի կենտրոնակայանի շինարարն ու գլխավոր ճարտարապետն էր. Հարիսոնը գլխավորում էր միջազգային ճարտարապետների կոմիտեն, որի կազմում էին Օսկար Նիմեյերը (ով մշակել էր հանձնաժողովի կողմից հաստատված բնօրինակ ծրագիրը) և Լե Կորբյուզիեն։ Հարիսոնի և նրա ֆիրմայի կողմից նախագծված Նյու Յորքի այլ նշանակալից շենքերը ներառում էին Մետրոպոլիտեն օպերայի շենքը, Լինքոլն կենտրոնի գլխավոր հատակագիծը և Ջոն Քենեդու միջազգային օդանավակայանը [4]:

Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոնի «Ապակե տունը» Նյու Քանանում, Կոնեկտիկուտ (1953)

-

ԻԴՍ կենտրոնը Մինեապոլիսում, Մինեսոտա, Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոն (1969–72)

-

Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոնի բյուրեղյա տաճարը (1977–80)

-

Ուլիոսի շենկը ՀաուստոնումՏեխաս Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսնի կողմից (1981–1983)

-

ՊՊԳ Փլեյս Փիթսբուրգում, Փենսիլվանիա, Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոն (1981–84)

Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոնը (1906–2005) ամերիկյան ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության ամենաերիտասարդ և վերջին խոշոր դեմքերից էր։ Նա վերապատրաստվել է Հարվարդում Վալտեր Գրոպիուսի մոտ, այնուհետև 1946-1954 թվականներին եղել է Մետրոպոլիտեն արվեստի թանգարանի ճարտարապետության և ժամանակակից դիզայնի բաժնի տնօրեն։ 1947 թվականին նա հրատարակել է գիրք Լյուդվիգ Միես վան դեր Ռոեի մասին, իսկ 1953 թվականին նախագծել է իր սեփական նստավայրը, ապակե տունը Նյու Քանանում, Կոնեկտիկուտ՝ Միեսի Ֆարնսվորթ տան օրինակով: 1955 թվականից սկսած նա սկսեց գնալ իր սեփական ուղղությամբ՝ աստիճանաբար շարժվելով դեպի էքսպրեսիոնիզմ՝ դիզայներներով, որոնք գնալով հեռանում էին ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության ուղղափառությունից: Նրա վերջնական և վճռական ընդմիջումը ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության հետ Ա և Թ շենքն էր (հետագայում հայտնի է որպես Սոնի Թովեր), իսկ այժմ Նյու Յորքի Մեդիսոն պողոտա 550 (1979 թ.) էապես մոդեռնիստական երկնաքեր, որն ամբողջությամբ փոխվել է շրջանաձև կոտրված ֆրոնտոնի ավելացմամբ։ Այս շենքը, ընդհանուր առմամբ, համարվում է ԱՄՆ-ում հետմոդեռն ճարտարապետության սկիզբը[4]:

Էերո Սաարինեն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Դարպասի կամարը Սենթ Լուիսում, Միսսուրի (1948–1965)

-

Ջեներալ մոտերս տեխնիկական կենտրոնի գլխավոր շենքը (1949–55)

-

Ինգալսի սահադաշտը Նյու Հեյվենում, Կոնեկտիկուտ (1953–58)

-

ՏՎԱ տերմինալը Նյու Յորքի ՋՖԿ օդանավակայանում, Էերո Սաարինենի կողմից (1956–62)

Էերո Սաարինենը (1910–1961) Էլիել Սաարինենի՝ Արտ Նովոյի շրջանի ամենահայտնի ֆին ճարտարապետի որդին էր, ով գաղթել է ԱՄՆ 1923 թվականին, երբ Էրոն տասներեք տարեկան էր։ Նա արվեստ և քանդակ է սովորել ակադեմիայում, որտեղ դասավանդել է իր հայրը, այնուհետև Փարիզի Աքադեմիե դե լա Գղանդե Չամիեղե ակադեմիայում, նախքան Յեյլի համալսարանում ճարտարապետություն ուսանելը: Նրա ճարտարապետական նախագծերն ավելի շատ նման էին հսկայական քանդակի, քան ավանդական ժամանակակից շինությունների, նա կտրվեց նրբագեղ տուփերից, որոնք ոգեշնչված էին Միես վան դեր Ռոեի կողմից և փոխարենը օգտագործեց ավլող կորեր և պարաբոլներ, ինչպես թռչունների թևերը: 1948 թվականին առաջ եկավ Միսսուրի նահանգի Սենթ Լուիս քաղաքում 192 մետր բարձրությամբ պարաբոլիկ կամարի տեսքով հուշարձան ստեղծելու գաղափարը, որը պատրաստված է չժանգոտվող պողպատից (1948 թ.): Այնուհետև նա նախագծեց Ջեներալ Մոտորս տեխնիկական կենտրոնը Ուորենում, Միչիգան (1949–55), ապակե մոդեռնիստական տուփ Միես վան դեր Ռոեի ոճով, որին հաջորդեց ԻԲՄ հետազոտական կենտրոնը Յորքթաունում, Վիրջինիա (1957–61): Նրա հաջորդ աշխատանքները ոճային մեծ շեղում էին. նա ստեղծել է հատկապես ցայտուն քանդակագործական ձևավորում Ինգալսի սահադաշտի համար, որը գտնվում է Նյու Հևենում, Կոնեկտիկուտ (1956–59 թթ., սառցե դահուկային սահադաշտ՝ պարաբոլիկ տանիքով, որը կախված է մալուխներից, որը ծառայում է որպես հաջորդ և ամենահայտնի աշխատանքի՝ ԹՎԱ տերմինալի նախնական մոդելը,Նյու Յորքի JFK օդանավակայան (1956–1962): Նրա հայտարարած մտադրությունն էր նախագծել մի շենք, որը կլինի առանձնահատուկ և հիշարժան, ինչպես նաև այնպիսի շենք, որը կգրավի ուղևորների առանձնահատուկ ոգևորությունը ճանապարհորդությունից առաջ: Կառույցը բաժանված է չորս սպիտակ բետոնե պարաբոլիկ պահարանների, որոնք միասին թռչելու համար նստած գետնի վրա թռչնի են հիշեցնում: Չորս կոր տանիքի կամարներից յուրաքանչյուրն ունի երկու կողմ՝ Y ձևով կցված սյուներին հենց կառուցվածքից դուրս: Յուրաքանչյուր պատյանի անկյուններից մեկը թեթևակի բարձրացված է, իսկ մյուսը՝ կցված է կառույցի կենտրոնին։ Տանիքը միացված է գետնին ապակյա վարագույրներով։ Շենքի ներսում գտնվող բոլոր մանրամասները՝ ներառյալ նստարանները, հաշվիչները, շարժասանդուղքները և ժամացույցները, նախագծված են նույն ոճով[4]:

Լուի Կան[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Լուի Կանի Ռոչեսթերի առաջին ունիտար եկեղեցին (1962)

-

Լուի Կանի Սալկի ինստիտուտը (1962–63)

-

Ռիչարդ Բժշկական հետազոտության լաբարատորիա Լուիզ Կաինի կողմից (1957–61)

-

Քիմբելի արվեստի թանգարան Ֆորտ Ուորթում, Տեխաս (1966–72)

-

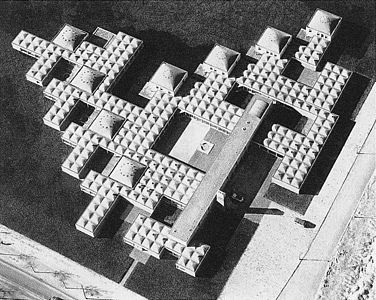

Ազգային խորհրդարանի շենքը Դաքայում, Բանգլադեշ (1962–74)

Լուի Կանը (1901–74) մեկ այլ ամերիկացի ճարտարապետ էր, ով հեռացավ ապակե տուփի Միես Վան Դե Րոհի մոդելից և գերակշռող միջազգային ոճի այլ դոգմաներից:Նա փոխառել է ոճերի և բառապաշարների լայն տեսականի, ներառյալ նեոկլասիցիզմը։ Նա ճարտարապետության պրոֆեսոր էր Յեյլի համալսարանում 1947-1957 թվականներին, որտեղ նրա ուսանողների թվում էր Էերո Սաարինենը: 1957 թվականից մինչև իր մահը եղել է Փենսիլվանիայի համալսարանի ճարտարապետության պրոֆեսոր։ Նրա աշխատանքն ու գաղափարները ազդեցին Ֆիլիպ Ջոնսոնի, Մինորու Յամասակիի և Էդվարդ Դուրել Սթոունի վրա, երբ նրանք շարժվեցին դեպի ավելի նեոկլասիկական ոճ: Ի տարբերություն Միեսի, նա չէր փորձում իր շենքերը թեթև տեսք հաղորդել. նա կառուցում էր հիմնականում բետոնով և աղյուսով և իր շենքերը դարձնում էր մոնումենտալ և ամուր: Ի տարբերություն Միեսի, նա չէր փորձում իր շենքերը թեթև տեսք հաղորդել, նա կառուցում էր հիմնականում բետոնով և աղյուսով և իր շենքերը դարձնում էր մոնումենտալ և ամուր: Նա նկարել է տարբեր աղբյուրների լայն տեսականի. Ռիչարդսի բժշկական հետազոտական լաբորատորիաների աշտարակները ոգեշնչված էին Վերածննդի քաղաքների ճարտարապետությամբ, որը նա տեսել էր Իտալիայում որպես 1950 թվականին Հռոմի Ամերիկյան ակադեմիայի ռեզիդենտ ճարտարապետ: Կանի նշանավոր շենքերը Միացյալ Նահանգներում ներառում են Ռոչեսթերի Առաջին ունիտար եկեղեցին Նյու Յորքում (1962), և Քիմբալի արվեստի թանգարանը Ֆորտ Ուորթում, Տեխաս (1966–72): Հետևելով Լե Կորբյուզիեի և Հնդկաստանի Հարյանա և Փենջաբ նահանգի մայրաքաղաք Չանդիգարի կառավարական շենքերի օրինակին, Կանը նախագծել է Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban (Ազգային ժողովի շենք) Դաքայում, Բանգլադեշ (1962–74), երբ այդ երկիրը անկախացավ Պակիստանից։ Դա Կանի վերջին աշխատանքն էր[4]:

Ի. Մ. Պեի[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Կանաչ շենք Մասաչուսեթսի տեխնոլոգիական ինստիտուտում, Ի. Մ. Pei (1962–64)

-

Մթնոլորտային հետազոտությունների ազգային կենտրոն Բոլդերում, Կոլորադո, Ի. Մ. Պեյ (1963–67)The

-

Մթնոլորտային հետազոտությունների ազգային կենտրոն Բոլդերում, Կոլորադո, Ի. Մ. Պեյ (1963–67)

-

Վաշինգտոնի Արվեստի ազգային պատկերասրահի արևելյան թեւը, հեղինակ՝ I M. Pei (1978)

-

Փարիզի Լուվրի թանգարանի բուրգը, հեղինակ՝ Ի. Մ. Պեյ (1983–89)

Ի. Մ. Պեի (1917–2019) ուշ մոդեռնիզմի և հետմոդեռն ճարտարապետության դեբյուտի գլխավոր գործիչն էր։ Նա ծնվել է Չինաստանում, կրթություն է ստացել ԱՄՆ-ում՝ սովորելով ճարտարապետություն Մասաչուսեթսի տեխնոլոգիական ինստիտուտում։ Մինչ ճարտարապետական դպրոցն այնտեղ դեռ սովորում էր Բեաուքս Արտ ճարտարապետության ոճով, Պեյը հայտնաբերեց Լե Կորբյուզիեի գրվածքները, և 1935 թվականին Լե Կորբյուզիեի երկօրյա այցը համալսարան մեծ ազդեցություն ունեցավ Պեյի ճարտարապետության գաղափարների վրա: 1930-ականների վերջին նա տեղափոխվեց Հարվարդի դիզայնի բարձրագույն դպրոց, որտեղ սովորեց Վալտեր Գրոպիուսի և Մարսել Բրյերի հետ և խորապես ներգրավվեց մոդեռնիզմի մեջ[43]: Պատերազմից հետո նա աշխատել է խոշոր նախագծերի վրա նյույորքյան անշարժ գույքի ծրագրավորող Ուիլյամ Զեքենդորֆի համար, նախքան հեռանալը և հիմնել իր սեփական ընկերությունը: Առաջին շենքերից մեկը, որը նախագծել էր իր սեփական ընկերությունը, Մասաչուսեթսի տեխնոլոգիական ինստիտուտի Կանաչ շենքն էր: Մինչև մաքուր մոդեռնիստական ճակատը հիանում էր, շենքը անսպասելի խնդիր առաջացրեց. այն ստեղծել է քամու թունելի էֆեկտ, և ուժեղ քամու դեպքում դռները բացել չեն կարող։ Պեյին ստիպել են թունել կառուցել, որպեսզի այցելուները կարողանան շենք մտնել ուժեղ քամիների ժամանակ:

1963-ից 1967 թվականներին Պեյը նախագծել է Մեսա լաբորատորիան Մթնոլորտային հետազոտությունների ազգային կենտրոնի համար Բոլդերից դուրս, Կոլորադո, բաց տարածքում՝ Ռոքի լեռների ստորոտում: Նախագիծը տարբերվում էր Պեյի ավելի վաղ քաղաքային աշխատանքից: Այն կհանգչեր Ժայռոտ լեռների ստորոտում գտնվող բաց տարածքում։ Նրա դիզայնը ապշեցուցիչ շեղվում էր ավանդական մոդեռնիզմից, թվում էր, թե այն փորագրված էր սարի ափից[43]:

Ուշ մոդեռնիստական շրջանում արվեստի թանգարանները շրջանցում էին երկնաքերերը՝ որպես ամենահեղինակավոր ճարտարապետական նախագծեր: Նրանք ավելի մեծ հնարավորություններ էին տալիս նորարարության ձևով և ավելի տեսանելիությամբ: Պեյը հաստատվեց իր դիզայնով Հերբերտ Ֆ. Ջոնսոնի արվեստի թանգարանի համար Իթաքայում, Նյու Յորքի Քորնելի համալսարանում (1973 թ.), որը գովաբանվեց փոքր տարածքի երևակայական օգտագործման և դրա շուրջը գտնվող լանդշաֆտի և այլ շենքերի նկատմամբ հարգանքի համար: Սա հանգեցրեց ժամանակաշրջանի թանգարանային ամենակարևոր նախագծերից մեկի՝ Վաշինգտոնի Արվեստի ազգային պատկերասրահի նոր արևելյան թևի հանձնմանը, որն ավարտվեց 1978 թվականին, և Պեյի ամենահայտնի նախագծերից՝ Լուվրի թանգարանն է Փարիզում (1983–89)։ Պեյն ընտրեց բուրգը որպես ձև, որը լավագույնս ներդաշնակվում էր պատմական Լուվրի Վերածննդի և նեոկլասիկական ձևերի հետ, ինչպես նաև Նապոլեոնի և Բուրգերի ճակատամարտի հետ կապերի համար: Բուրգի յուրաքանչյուր երեսը հենված է չժանգոտվող պողպատի 128 ճառագայթներով, որոնք աջակցում են 675 ապակիների վահանակներին, յուրաքանչյուրը 2,9 x 1,9 մետր (9 ft 6 in x 6 ft 3 iny)[4]:

Ֆազլուր Ռահման Խան[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Չիկագոյում գտնվող Ջոն Հենքոքի կենտրոնը Ֆազլուր Ռահման Խանի կողմից առաջին շենքն էր, որն օգտագործեց X-bracing-ը` ճարմանդային խողովակի դիզայն ստեղծելու համար:

-

Չիկագոյում գտնվող Ուիլս Թովերը առաջին շենքն էր, որն օգտագործեց փաթեթավորված խողովակի դիզայնը:

1955 թվականին, աշխատանքի անցնելով Սկիդմորե, Օինգս և Մերիլ (SOM) ճարտարապետական ընկերությունում, նա սկսեց աշխատել Չիկագոյում։ Նրան գործընկեր դարձրին 1966 թվականին: Նա իր կյանքի մնացած մասը աշխատեց ճարտարապետ Բրյուս Գրեհեմի հետ կողք կողքի[44]: Խանը ներկայացրեց նախագծման մեթոդներ և գաղափարներ շենքերի ճարտարապետության մեջ նյութի արդյունավետ օգտագործման համար: Նրա առաջին շենքը, որն օգտագործում էր խողովակի կառուցվածքը, Շագանակագույն Դե-Վիտ բնակելի շենքն էր[45]: 1960-ականներին և 1970-ականներին նա հայտնի դարձավ Չիկագոյի 100-հարկանի Ջոն Հենքոք կենտրոնի իր նախագծերով, որն առաջին շենքն էր, որն օգտագործեց խողովակների դիզայնը և 110 հարկանի Սիերս Թավերը, որը վերանվանվեց Ուիլս Թավեր` ամենաբարձր շենքը աշխարհում 1973-ից մինչև 1998 թվականը, որն առաջին շենքն էր, որն օգտագործեց շրջանակված խողովակի դիզայնը:

Նա կարծում էր, որ ինժեներներին անհրաժեշտ է կյանքի ավելի լայն հեռանկար՝ ասելով. «Տեխնիկական մարդը չպետք է կորչի իր սեփական տեխնոլոգիայի մեջ, նա պետք է կարողանա գնահատել կյանքը, և կյանքը արվեստ է, դրամա, երաժշտություն և ամենակարևորը՝ մարդիկ»: Խանի անձնական փաստաթղթերը, որոնց մեծ մասը նրա մահվան պահին եղել է նրա գրասենյակում, պահվում են Չիկագոյի արվեստի ինստիտուտի Րյերսոն և Բուրնհամ գրադարաններում: Ֆազլուր խանի հավաքածուն ներառում է ձեռագրեր, էսքիզներ, ձայներիզներ, սլայդներ և նրա ստեղծագործությանը վերաբերող այլ նյութեր:

Բարձր շենքերի կառուցվածքային համակարգերի մշակման Խանի հիմնական աշխատանքը մինչ օրս օգտագործվում է որպես ելակետ բարձր շենքերի նախագծման տարբերակների քննարկման ժամանակ: Խողովակների կառույցներն այդ ժամանակվանից օգտագործվել են բազմաթիվ երկնաքերերում, այդ թվում՝ Համաշխարհային առևտրի կենտրոնի, Աոն կենտրոնի, Պետրոնաս աշտարակների, Ջին Մաո շենքի, Չինաստանի Բանկ Աշտարակի և 1960-ականներից ի վեր կառուցված ավելի քան 40 հարկանի այլ շենքերի կառուցման համար: Խողովակների կառուցվածքի նախագծման ուժեղ ազդեցությունն ակնհայտ է նաև աշխարհի ներկայիս ամենաբարձր երկնաքերում՝ Դուբայի Բուրջ Խալիֆայում: Ըստ ամենօրյա հեռագրի Սթիվեն Բեյլիի:

| Խանը հորինել է բարձրահարկ շենք կառուցելու նոր ձև: ... Այսպիսով, Ֆազլուր խանը ստեղծեց ոչ սովորական երկնաքերը: Հակելով պողպատե շրջանակի տրամաբանությունը՝ նա որոշեց, որ շենքի արտաքին ծրարը կարող է լինել՝ հաշվի առնելով բավական խարիսխը, շրջանակը և ամրացումը, հենց կառուցվածքը: Սա շենքերն էլ ավելի թեթևացրեց։ «Կոմպլեկտավորված խողովակը» նշանակում էր, որ շենքերն այլևս կարիք չունեն տուփի տեսք ունենալ, դրանք կարող են դառնալ քանդակ: Խանի զարմանահրաշ պատկերացումները, որոնց անունը Օբաման ստուգել էր անցյալ տարի Կահիրեի համալսարանի իր ելույթում, փոխեց գերբարձր շենքերի և՛ տնտեսագիտությունը, և՛ մորֆոլոգիան: Եվ դա հնարավոր դարձրեց Բուրջ Խալիֆային. համաչափորեն Բուրջն օգտագործում է պողպատի թերևս կեսը, որը պահպանողականորեն աջակցում է Empire State Building-ին: ... Բուրջ Խալիֆան նրա համարձակ, թեթև դիզայնի վերջնական արտահայտություն նրա համարձակ, թեթև դիզայնի փիլիսոփայությունըէ[46] |

Միմոր Յամասակի[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Համաշխարհային առևտրի կենտրոնի երկվորյակ աշտարակները (1973–2001) Ստորին Մանհեթենում Մինորու Յամասակի (1912-1986 թ.)

-

Սենտեր Պլազա Թովերը Լոս Անջելեսում, Կալիֆորնիա (1975)

-

Վան Ուդվորդ ավենյու Դեթրոյթում, Միչիգան (1962)

Միացյալ Նահանգներում Մինորու Յամասակին մեծ անկախ հաջողություն ունեցավ՝ կիրառելով այն ժամանակվա բարդ խնդիրների եզակի ինժեներական լուծումներ, ներառյալ այն տարածքը, որը վերելակների հորանները զբաղեցնում էին յուրաքանչյուր հարկում, և հաղթահարելով իր անձնական վախը բարձրությունից: Այս ժամանակահատվածում նա ստեղծեց մի շարք գրասենյակային շենքեր, որոնք հանգեցրին 1964 թվականին Համաշխարհային առևտրի կենտրոնի 1360 ֆտ (410 մ) աշտարակների նորարարական նախագծմանը, որը սկսեց շինարարությունը 1966 թվականի մարտի 21-ին[47]: Աշտարակներից առաջինն ավարտվել է 1970 թվականին[48]: Նրա շենքերից շատերը ներկայացնում են մակերեսային մանրամասներ՝ ոգեշնչված գոթական ճարտարապետության սրածայր կամարներից և օգտագործում են չափազանց նեղ ուղղահայաց պատուհանները: Նեղ պատուհաններով այս ոճը առաջացել է բարձունքների հանդեպ նրա անձնական վախից[49]: Համաշխարհային առևտրի կենտրոնի նախագծման մեկ կոնկրետ նախագծային մարտահրավեր՝ կապված վերելակային համակարգի արդյունավետության հետ, որը եզակի էր աշխարհում: Յամասակին միավորել է այն ժամանակվա ամենաարագ վերելակները, որոնք աշխատում էին րոպեում 1700 ֆուտ արագությամբ: Յուրաքանչյուր աշտարակի միջուկում մեծ ավանդական վերելակի լիսեռ տեղադրելու փոխարեն Յամասակին ստեղծեց Երկվորյակ աշտարակների «Սկայլոբը» համակարգը։ Սկայլոբի դիզայնը ստեղծեց երեք առանձին, միացված վերելակային համակարգեր, որոնք կսպասարկեին շենքի տարբեր հատվածներին՝ կախված նրանից, թե որ հարկն է ընտրվել՝ խնայելով ավանդական լիսեռի համար օգտագործվող տարածքի մոտավորապես 70%-ը: Պահպանված տարածքն այնուհետև օգտագործվել է գրասենյակային տարածքի համար[50]: Ի հավելումն այս նվաճումների, նա նաև նախագծել էր Պրուիտ-Իգոե բնակարային նախագիծը, որը երբևէ կառուցված Միացյալ Նահանգներում կառուցված ամենամեծ բնակարանային նախագիծը, որն ամբողջությամբ քանդվեց 1976 թվականին շուկայական վատ պայմանների և բուն շենքերի անմխիթար վիճակի պատճառով: Առանձին-առանձին, նա նաև նախագծել էր Century Plaza Towers-ը և One Woodward Avenue-ը, ի թիվս 63 այլ նախագծերի, որոնք նա մշակել էր իր կարիերայի ընթացքում:

Հետպատերազմյան մոդեռնիզմը Եվրոպայում (1945–1975)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Սուրբ Մարիա Դե Լա Տուրետ Կորբյուզիե և Յաննիս Քսենակիս (1956–60)

-

Ազգային թագավորական թատրոն, Լոնդոն, Դենիս Լասդուն (1967–1976))

-

Տեխնոլոգիական համալսարանի լսարան. Հելսինկի, Ալվար Աալտո (1964)

-

Համալսարանական հիվանդանոցային կենտրոն Լիեժում, Բերգուն, Չարլզ Վանդենհով (1962-62)

-

Պիրելի աշտարակը Միլանում, Ջիո Պոնտիի և Պիեր Լուիջի Ներվիի կողմից (1958–60)

-

Դե Մաեյթ հիմնադրամը, Ջոզե Լուիզ Սերտ (1959–1964)

-

Սուրբ Մարտինի եկեղեցի, Իդշտեյն Գերմանիա, Յոհաննես Կրան (1965)

-

Վարշավայի Կենտրոնական երկաթուղային կայարան Լեհաստանում, Արսենիուս Ռոմանովիչ (1975)

-

Ամստերդամի մունիցիպալ որբանոց՝ Ալդո վան Էյքի (1960 թ.), «Թվի էսթետիկա», ճարտարապետական շարժում Ստրուկտուալիզմ:

Ֆրանսիայում Լե Կորբյուզեն մնաց ամենահայտնի ճարտարապետը, թեև այնտեղ քիչ շենքեր կառուցեց: Նրա ամենահայտնի ուշ գործը Էվրո-սյուր-լ'Արբրեսլի Սուրբ Մարի դը Լա Տուրետ մենաստանն էր: Հում բետոնից կառուցված մենաստանը խստաշունչ էր և առանց զարդանախշերի՝ ոգեշնչված միջնադարյան վանքերից, որոնք նա այցելել էր Իտալիա իր առաջին ճամփորդության ժամանակ[27]:

Մեծ Բրիտանիայում մոդեռնիզմի հիմնական դեմքերն էին Ուելս Քոութսը (1895–1958), ՖՌՍ Յորքը (1906–1962), Ջեյմս Սթերլինգը (1926–1992) և Դենիս Լասդունը (1914–2001): Լասդունի ամենահայտնի ստեղծագործությունը Թեմզայի հարավային ափին գտնվող Թագավորական ազգային թատրոնն է (1967–1976)։ Նրա հում բետոնն ու բլոկավոր ձևը վիրավորեց բրիտանացի ավանդապաշտներին. Մեծ Բրիտանիայի թագավոր Չարլզ III-ը այն համեմատել է ատոմակայանի հետ:

Բելգիայում գլխավոր գործիչն էր Չարլզ Վանդենհովը (ծնված 1927 թ.), ով կառուցեց մի շարք շենքեր Լիեժի Համալսարանական հիվանդանոցային կենտրոնի համար: Նրա ավելի ուշ աշխատանքները սկսեցին գունեղ վերաիմաստավորել պատմական ոճերը, ինչպիսին է Պալադյան ճարտարապետությունը[4]:

Ֆինլանդիայում ամենաազդեցիկ ճարտարապետը Ալվար Աալտոն էր, ով մոդեռնիզմի իր տարբերակը հարմարեցրեց սկանդինավյան լանդշաֆտին, լույսին և նյութերին, մասնավորապես՝ փայտի օգտագործմանը: Երկրորդ համաշխարհային պատերազմից հետո նա ճարտարապետություն է դասավանդել ԱՄՆ-ում։ Դանիայում Արնե Յակոբսենը մոդեռնիստներից ամենահայտնին էր, ով նախագծում էր կահույք, ինչպես նաև խնամքով չափված շենքեր:

Իտալիայում ամենահայտնի մոդեռնիստը Ջիո Պոնտին էր, ով հաճախ աշխատում էր երկաթբետոնի մասնագետ, կառուցվածքային ինժեներ Պիեր Լուիջի Ներվիի հետ: Ներվին ստեղծեց բացառիկ երկարության բետոնե ճառագայթներ՝ քսանհինգ մետր, ինչը թույլ էր տալիս ավելի մեծ ճկունություն ձևերի մեջ և ավելի մեծ բարձրություններում: Նրանց ամենահայտնի դիզայնը Միլանում գտնվող Պիրելի շենքն էր (1958–1960), որը տասնամյակներ շարունակ եղել է Իտալիայի ամենաբարձր շենքը[4]:

Իսպանացի ամենահայտնի մոդեռնիստը կատալոնացի ճարտարապետ Խոսեպ Լյուիս Սերտն էր, ով մեծ հաջողությամբ աշխատել է Իսպանիայում, Ֆրանսիայում և ԱՄՆ-ում։ Իր վաղ կարիերայի ընթացքում նա որոշ ժամանակ աշխատել է Լե Կորբյուզիեի ղեկավարությամբ և նախագծել է իսպանական տաղավարը 1937 թվականի Փարիզի ցուցահանդեսի համար: Նրա հետագա ուշագրավ աշխատանքները ներառում էին «Ֆոնդեշիոն Մեգտ»-ը Սեն-Պոլ-դե-Պրովանսում, Ֆրանսիա (1964), և Հարվարդի գիտական կենտրոնը Քեմբրիջում, Մասաչուսեթս: Նա աշխատել է Հարվարդի դիզայնի դպրոցում որպես ճարտարապետության դեկան։

Նշանավոր գերմանացի մոդեռնիստներից են Յոհաննես Կրանը, ով կարևոր դեր է խաղացել Երկրորդ համաշխարհային պատերազմից հետո գերմանական քաղաքների վերակառուցման գործում և կառուցել մի քանի կարևոր թանգարաններ և եկեղեցիներ, մասնավորապես՝ Սուրբ Մարտինը, Իդշտեյնը, որոնք հմտորեն համադրել են քարե որմնանկարը, բետոնը և ապակին: Ոճի առաջատար ավստրիացի ճարտարապետներից են Գուստավ Պեյխլը, ում հետագա աշխատանքները ներառում են Գերմանիայի Դաշնային Հանրապետության արվեստի և ցուցահանդեսային կենտրոնը Բոննում, Գերմանիա (1989):

Լատինական Ամերիկա[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

-

Առողջապահության և կրթության նախարարություն Ռիո դե Ժանեյրոյում Լուչիո Կոստա (1936–43)

-

ՄԱՄ Ռիո թանգարան, Աֆոնսո Էդուարդո Ռեյդի (1960)

-

Ազգային Կոնգրեսի շենքը Բրազիլիայում Օսկար Նիմեյերի կողմից (1956–61)

-

Օսկար Նիմեյերի Բրազիլիայի տաճարը (1958–1970)

-

Պլանալտո պալատ, Բրազիլիայի նախագահի գրասենյակները, հեղինակ՝ Օսկար Նիմեյեր (1958–60)

-

Սան Պաուլոյի արվեստի թանգարան,ՄԱՍՊ, հեղինակ՝ Լինա Բո Բարդի (1957–68)

-

Լատինական Ամերիկայի աշտարակ Մեքսիկա քաղաքում Աուգուստո Հ. Ալվարեզ (1956)

-

Լուիս Բարագանի տան և ստուդիայի ինտերիերը Մեխիկոյում, հեղինակ՝ Լուիս Բարագան (1948)

-

Րեսիդենսիա դել Պարքուե Բոգոտաում Ռոգելիո Սալմոնա (1965–1970)

Ճարտարապետության պատմաբանները երբեմն լատինաամերիկյան մոդեռնիզմը պիտակավորում են որպես «արևադարձային մոդեռնիզմ»։ Սա արտացոլում է ճարտարապետներին, ովքեր մոդեռնիզմը հարմարեցրել են արևադարձային կլիմայական պայմաններին, ինչպես նաև Լատինական Ամերիկայի սոցիալ-քաղաքական համատեքստերին[51]:

Բրազիլիան դարձավ ժամանակակից ճարտարապետության ցուցափեղկ 1930-ականների վերջին Լուսիո Կոստայի (1902–1998) և Օսկար Նիմեյերի (1907–2012) աշխատանքների շնորհիվ։ Կոստան գլխավորում էր, իսկ Նիմեյերը համագործակցում էր Ռիո դե Ժանեյրոյում Կրթության և Առողջապահության նախարարության (1936–43) և Բրազիլիայի տաղավարում 1939 թվականին Նյու Յորքի համաշխարհային ցուցահանդեսում։ Պատերազմից հետո Նիմեյերը Լե Կորբյուզիեի հետ միասին ստեղծեց ՄԱԿ-ի կենտրոնակայանի ձևը, որը կառուցվել էր Ուոլտեր Հարիսոնի կողմից:

Լուչիո Կոստան նաև ընդհանուր պատասխանատվություն էր կրում Բրազիլիայում ամենահամարձակ մոդեռնիստական նախագծի համար. Բրազիլիայի նոր մայրաքաղաքի ստեղծումը, որը կառուցվել է 1956-1961 թվականներին: Կոստան կազմել է գլխավոր հատակագիծը, որը շարադրված է խաչի տեսքով, որի կենտրոնում կառավարական հիմնական շենքերն են: Նիմեյերը պատասխանատու էր կառավարական շենքերի նախագծման համար, ներառյալ Նախագահի պալատը, Ազգային ժողովը, որը բաղկացած է երկու աշտարակից օրենսդիր մարմնի երկու ճյուղերի համար և երկու նիստերի դահլիճներից, մեկը գմբեթով, իսկ մյուսը շրջված գմբեթով: Նիմեյերը նաև կառուցեց տաճարը, տասնութ նախարարություն և բնակարանային հսկա բլոկներ, որոնցից յուրաքանչյուրը նախատեսված էր երեք հազար բնակչի համար, որոնցից յուրաքանչյուրն ունի իր դպրոցը, խանութները և մատուռը: Մոդեռնիզմը կիրառվել է և՛ որպես ճարտարապետական սկզբունք, և՛ որպես հասարակության կազմակերպման ուղեցույց, ինչպես ուսումնասիրվել է «Մոդեռնիստական քաղաքում»[52]:

1964 թվականին Բրազիլիայում տեղի ունեցած ռազմական հեղաշրջումից հետո Նիմեյերը տեղափոխվեց Ֆրանսիա, որտեղ նա նախագծեց Ֆրանսիայի կոմունիստական կուսակցության մոդեռնիստական շտաբը Փարիզում (1965–1980), որը մանրանկարչություն էր Միավորված ազգերի կազմակերպության իր ծրագրին[4]:

Մեքսիկան նույնպես ուներ նշանավոր մոդեռնիստական շարժում։ Կարևոր դեմքերից են Ֆելիքս Կանդելան՝ ծնված Իսպանիայում, ով Մեքսիկա է գաղթել 1939 թվականին; նա մասնագիտացել է անսովոր պարաբոլիկ ձևերով բետոնե կոնստրուկցիաների մեջ: Մեկ այլ կարևոր գործիչ էր Մարիո Պանին, ով նախագծել էր Մեխիկոյի Երաժշտության ազգային կոնսերվատորիան (1949), և Թորրո Ինսիգնիա(1988): Պանին նաև մեծ դեր ունեցավ 1950-ականներին Մեխիկոյի նոր համալսարանի կառուցման գործում՝ Խուան Օ'Գորմանի, Էուջենիո Պեշարդի և Էնրիկե դել Մորալի կողքին: Տորրո Լատինամերիկացին, որը նախագծվել է Ավգուստո Հ. Ալվարեսի կողմից, Մեխիկոյի ամենավաղ մոդեռնիստական երկնաքերերից մեկն էր (1956 թ.), այն հաջողությամբ դիմակայեց 1985 թվականի Մեխիկոյի երկրաշարժին, որը ավերեց բազմաթիվ այլ շենքեր քաղաքի կենտրոնում: Պեդրո Ռամիրեսը Վասկեսը և Ռաֆայել Միխարեսը նախագծել են Օլիմպիական մարզադաշտը 1968 թվականի Օլիմպիական խաղերի համար, իսկ Անտոնի Պեյրին և Կանդելան՝ Սպորտի պալատը։ Լուիս Բարագանը մեքսիկական մոդեռնիզմի մեկ այլ ազդեցիկ գործիչ էր. Մեխիկոյում նրա չմշակված բետոնե նստավայրն ու ստուդիան արտաքինից բլոկանոցի տեսք ունի, մինչդեռ ներսից այն առանձնանում է ձևի մեծ պարզությամբ, մաքուր գույներով, առատ բնական լույսով, իսկ ստորագրություններից մեկն առանց ճաղավանդակի սանդուղք է: Նա արժանացել է Պրիցկերի ճարտարապետության մրցանակին 1980 թվականին, իսկ տունը 2004 թվականին հռչակվել է ՅՈՒՆԵՍԿՕ-ի համաշխարհային ժառանգության օբյեկտ[4]:

Ասիա և Ավստրալիա[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]