«Մասնակից:Արտաշես Գրիգորյան/Ավազարկղ»–ի խմբագրումների տարբերություն

Appearance

Content deleted Content added

No edit summary Պիտակ՝ հետշրջված |

Հետ է շրջվում 9058321 խմբագրումը, որի հեղինակն է Արտաշես Գրիգորյան (քննարկում) մասնակիցը Պիտակներ՝ Հետ շրջել հետշրջված |

||

| Տող 68. | Տող 68. | ||

| Ըստ Վալերիուս Մաքսիմուսի՝ աթենացի երեք մեծ [[Ողբերգություն (ժանր)|ողբերգականներից]] ավագը, սպանվել է [[Կրիաներ|կրիայի]] կողմից, որը իր վրա է նետել արծիվը, որը նրա ճաղատ գլուխը շփոթել էր քարի հետ, որը հարմար էր սողունի պատյանը կոտրելու համար: [[Պլինիոս Ավագ|Պլինիոս Ավագն]] իր «Բնական պատմության» մեջ ավելացնում է, որ Էսքիլեսը դրսում էր մնում՝ կանխելու այն մարգարեությունը, որ նա սպանվելու էր այդ օրը «տան ընկնելու պատճառով»<ref name="Marvin"/><ref>{{citation |title=Naturalis Historiæ |author=Pliny the Elder |volume=Book X |chapter=chapter 3|author-link=Pliny the Elder}}</ref><ref name=tortue>{{citation |title=La tortue d'Eschyle et autres morts stupides de l'Histoire |isbn=978-2352042211 |publisher=Editions Les Arènes |year=2012}}</ref><ref name="McKeown2013">{{cite book|last=McKeown|first=J. C.|date=2013 |title=A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ADJpAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA136|location=Oxford, England|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|pages=136–137|isbn=978-0-19-998210-3}}</ref>։ |

| Ըստ Վալերիուս Մաքսիմուսի՝ աթենացի երեք մեծ [[Ողբերգություն (ժանր)|ողբերգականներից]] ավագը, սպանվել է [[Կրիաներ|կրիայի]] կողմից, որը իր վրա է նետել արծիվը, որը նրա ճաղատ գլուխը շփոթել էր քարի հետ, որը հարմար էր սողունի պատյանը կոտրելու համար: [[Պլինիոս Ավագ|Պլինիոս Ավագն]] իր «Բնական պատմության» մեջ ավելացնում է, որ Էսքիլեսը դրսում էր մնում՝ կանխելու այն մարգարեությունը, որ նա սպանվելու էր այդ օրը «տան ընկնելու պատճառով»<ref name="Marvin"/><ref>{{citation |title=Naturalis Historiæ |author=Pliny the Elder |volume=Book X |chapter=chapter 3|author-link=Pliny the Elder}}</ref><ref name=tortue>{{citation |title=La tortue d'Eschyle et autres morts stupides de l'Histoire |isbn=978-2352042211 |publisher=Editions Les Arènes |year=2012}}</ref><ref name="McKeown2013">{{cite book|last=McKeown|first=J. C.|date=2013 |title=A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ADJpAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA136|location=Oxford, England|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|pages=136–137|isbn=978-0-19-998210-3}}</ref>։ |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | [[ |

!scope="row" | [[Empedocles]] of [[Agrigento|Akragas]] |

||

| [[File:Empedocles in Thomas Stanley History of Philosophy.jpg|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Empedocles in Thomas Stanley History of Philosophy.jpg|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-430|format=hide}} {{c.|430 BC}} |

|||

| 430 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| |

| According to Diogenes Laërtius, the [[Pre-Socratic philosophy|Pre-Socratic philosopher]] from Sicily, who, in one of his surviving poems, declared himself to have become a "[[Daimon|divine being]]... no longer mortal",<ref name="Gregory">{{cite book|last1=Gregory|first1=Andrew |title=The Presocratics and the Supernatural: Magic, Philosophy and Science in Early Greece|date=2013|publisher=Bloomsbury Academic|location=New York City, New York and London, England|isbn=978-1-4725-0416-6|page=178|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AVMBAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA178}}</ref> tried to prove he was an immortal god by leaping into [[Mount Etna]], an active volcano.<ref>Diogenes Laërtius, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0258%3Abook%3D8%3Achapter%3D2 viii. 69] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170105030842/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0258:book=8:chapter=2 |date=5 January 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Meyer|first1=T. H. |title=Barefoot Through Burning Lava: On Sicily, the Island of Cain – An Esoteric Travelogue|date=2016|publisher=Temple Lodge Publishing|isbn=978-1906999940|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=osrZDAAAQBAJ&q=Empedocles+unusual+death&pg=PA16|access-date=11 September 2017|language=en}}</ref> This legend is also alluded to by the Roman poet [[Horace]].<ref>Horace, ''[[Ars Poetica (Horace)|Ars Poetica]]'', [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0065%3Acard%3D453 465–466]</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | [[ |

!scope="row" | [[Sophocles]] |

||

| [[File:Sophocles pushkin.jpg|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Sophocles pushkin.jpg|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-406|format=hide}} {{c.|406 BC}} |

|||

| 406 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| A number of "remarkable" legends concerning the death of another of the three great Athenian tragedians, are recorded in the late antique ''Life of Sophocles''. According to one legend, he choked to death on an unripe grape. Another says that he died of joy after hearing that his last play had been successful. A third account reports that he died of suffocation, after reading aloud a lengthy monologue from the end of his play ''[[Antigone (Sophocles play)|Antigone]],'' without pausing to take a breath for punctuation.<ref name="McKeown2013"/> |

|||

| Մի շարք «ուշագրավ» լեգենդներ երեք մեծ աթենացի ողբերգականներից ևս մեկի մահվան վերաբերյալ արձանագրված են ուշ անտիկ ''Սոֆոկլեսի կյանքում'': Համաձայն լեգենդներից մեկի՝ նա խեղդվել է չհասած խաղողով։ Մեկ ուրիշն ասում է, որ նա մահացել է ուրախությունից այն բանից հետո, երբ լսել է, որ իր վերջին պիեսը հաջողությամբ է պսակվել։ Երրորդ պատմությունը հայտնում է, որ նա մահացել է շնչահեղձությունից՝ բարձրաձայն կարդալով երկարատև մենախոսություն իր «<nowiki/>[[Անտիգոնե (ողբերգություն)|Անտիգոնե]]<nowiki/>» պիեսի վերջից՝ առանց կետադրական նշանների համար շունչ քաշելու<ref name="McKeown2013"/>։ |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | |

!scope="row" | Mithridates |

||

| |

| |

||

| 401 |

| {{dts|-401}} |

||

| |

| The Persian soldier who embarrassed his king, [[Artaxerxes II]], by boasting of killing his rival, [[Cyrus the Younger]] (who was the brother of Artaxerxes II), was executed by [[scaphism]]. The king's physician, [[Ctesias]], reported that Mithridates survived the insect torture for 17 days.<ref name=10tbd>{{cite book |chapter=10 truly bizarre deaths |title=Listverse.Com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/listversecomsult0000frat |chapter-url-access=registration |first=Jamie |last=Frater |publisher=Ulysses Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-56975-817-5 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/listversecomsult0000frat/page/12 12–14]}}</ref><ref name=acogc>{{cite book |title=A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization |page=102 |author=J. C. McKeown |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |year=2013 |isbn=978-0-19-998212-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ml7RErfHNg0C&pg=PT102 |quote=Ctesias, the Greek physician to Artaxerxes, the king of Persia, gives an appallingly detailed description of the execution inflicted on a soldier named Mithridates, who was misguided enough to claim the credit for killing the king's brother, Cyrus...}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | [[ |

!scope="row" | [[Democritus]] of [[Abdera, Thrace|Abdera]] |

||

| [[File:Hendrik ter Brugghen - Democritus.jpg|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Hendrik ter Brugghen - Democritus.jpg|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-370|format=hide}} {{c.|370 BC}} |

|||

| 370 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| |

| According to Diogenes Laërtius, the Greek [[atomism|Atomist]] philosopher died aged 109; as he was on his deathbed, his sister was greatly worried because she needed to fulfill her religious obligations to the goddess [[Artemis]] in the approaching three-day [[Thesmophoria]] festival. Democritus told her to place a loaf of warm bread under his nose, and was able to survive for the three days of the festival by sniffing it. He died immediately after the festival was over.<ref name="McKeown2013p157">{{cite book|last=McKeown|first=J. C.|date=2013 |title=A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ADJpAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA157|location=Oxford, England|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|page=157|isbn=978-0-19-998210-3}}</ref><ref name="Diogenesix43">Diogenes Laërtius, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0258%3Abook%3D9%3Achapter%3D7 ix.43] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170105030906/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0258:book=9:chapter=7 |date=5 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Antiphanes (comic poet)|Antiphanes]] |

|||

!Անտիֆանես |

|||

| |

| |

||

| {{dts|-310|format=hide}} {{c.|310 BC}} |

|||

| 310 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| |

|According to the ''[[Suda]]'', the renowned comic poet of the Middle [[Ancient Greek comedy|Attic comedy]] died after being struck by a [[pear]].<ref>{{Citation |url=https://www.cs.uky.edu/~raphael/sol/sol-entries/alpha/2735 |title=Suda α 2735}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Morti favolose degli antichi|last=Baldi|first=Dino|publisher=Quodlibet|year=2010|isbn=978-8874623372|location=Macerata|page=50|language=it}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | |

!scope="row" | [[Agathocles of Syracuse]] |

||

| [[File:Siracusa, agatocle, 25 litre, 310-300 ac ca.JPG|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Siracusa, agatocle, 25 litre, 310-300 ac ca.JPG|100px|center]] |

||

| 289 |

| {{dts|-289}} |

||

| [[ |

| The Greek [[tyrant]] of [[Syracuse, Sicily|Syracuse]] was murdered with a poisoned toothpick.<ref name="Marvin"/>{{Rp|104}}<ref>{{Cite magazine|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/let-us-now-praise-the-romantic-artful-versatile-toothpick-1-46061199/|title=Let Us Now Praise the Romantic, Artful, Versatile Toothpick|magazine=Smithsonian|first=Sue|last=Hubbell|date=Jan 1, 1997}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | [[ |

!scope="row" | [[Philitas of Cos]] |

||

| [[File:Antikythera philosopher.JPG|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Antikythera philosopher.JPG|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-270|format=hide}} {{c.|270 BC}} |

|||

| 270 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| |

|The Greek intellectual is said by [[Athenaeus]] to have studied arguments and erroneous word usage so intensely, that he wasted away and starved to death.<ref name="9.401e">[[Athenaeus]], ''[[Deipnosophistae]]'', [http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/Literature/Literature-idx?type=turn&entity=Literature.AthV2.p0115 9.401e].</ref> British classicist [[Alan Cameron (classical scholar)|Alan Cameron]] speculates that Philitas died from a [[wasting|wasting disease]] which his contemporaries joked was caused by his [[pedant]]ry.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=The Classical Quarterly |volume=41 |issue=2 |year=1991 |pages=534–538 |first=Alan |last=Cameron |title=How thin was Philitas? |doi=10.1017/S0009838800004717|s2cid=170699258}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | [[ |

!scope="row" | [[Zeno of Citium]] |

||

| [[File:Paolo Monti - Servizio fotografico (Napoli, 1969) - BEIC 6353768.jpg|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Paolo Monti - Servizio fotografico (Napoli, 1969) - BEIC 6353768.jpg|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-270|format=hide}} {{c.|262 BC}} |

|||

| 270 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| The Greek philosopher from Citium (Kition), Cyprus, tripped and fell as he was leaving the school, breaking his toe. Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe, "I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?" He died on the spot through holding his breath.{{sfn|Laërtius|1925|loc=§ 28}} |

|||

| Հույն փիլիսոփան Կիպրոսի Կիտիումից (Կիտիոն) դպրոցից դուրս գալու ժամանակ սայթաքել է և ընկել՝ կոտրելով ոտքի մատը։ Բռունցքով հարվածելով գետնին, նա մեջբերել է տող «Նիոբե»-ից. «Ես գալիս եմ, գալիս եմ, ինչո՞ւ ես ինձ կանչում»: Շունչը պահելով՝ տեղում մահացել է{{sfn|Laërtius|1925|loc=§ 28}}։ |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | [[ |

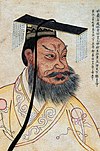

!scope="row" | [[Qin Shi Huang]] |

||

| [[File:QinShiHuang19century.jpg|100px|center]] |

| [[File:QinShiHuang19century.jpg|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-210|8|format=dmy}} |

|||

| Օգոստոս, 210 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| |

| The first [[emperor of China]], whose artifacts and treasures include the [[Terracotta Army]], died after ingesting several pills of [[mercury poisoning|mercury]], in the belief that it would grant him [[immortality|eternal life]].<ref>{{cite book |author=Wright, David Curtis |year=2001 |title=The History of China |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |page=[https://archive.org/details/historyofchina00wrig/page/49 49] |isbn=978-0-313-30940-3 |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofchina00wrig/page/49 |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/firstemperorsele00sima |title=The First Emperor |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-19-152763-0 |editor-last=Dawson |editor-first=Raymond |pages=[https://archive.org/details/firstemperorsele00sima/page/82 82], 150 |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref name="Nate Hopper">{{cite journal |url=http://www.esquire.com/blogs/culture/Royalty-and-their-strange-deaths |title=Royalty and their Strange Deaths |first=Nate |last=Hopper |date=4 February 2013 |journal=[[Esquire (magazine)|Esquire]] |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131119214553/http://www.esquire.com/blogs/culture/Royalty-and-their-strange-deaths |archive-date=19 November 2013}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | |

!scope="row" | [[Chrysippus]] of Soli |

||

| [[File:Chrysippos BM 1846.jpg|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Chrysippos BM 1846.jpg|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-206|format=hide}} {{c.|206 BC}} |

|||

| 206 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| |

| One ancient account of the death of the third-century BC [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] [[Stoicism|Stoic]] philosopher, tells that he [[Death from laughter|died of laughter]] after he saw a [[donkey]] eating his [[common fig|figs]]; he told a slave to give the donkey neat wine to drink with which to wash them down, and then, "...having laughed too much, he died" (Diogenes Laërtius 7.185).<ref name="Chrysippus">{{cite book|first=Diogenes|last= Laertius |title=Lives, Teachings and Sayings of the Eminent Philosophers, with an English translation by R.D. Hicks|year=1965|publisher=Harvard UP/W. Heinemann Ltd|location=Cambridge, Mass/London}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" | |

!scope="row" | [[Eleazar Avaran]] |

||

| [[File:Harley3240 f.28 ElephantDetail.jpg|100px|center]] |

| [[File:Harley3240 f.28 ElephantDetail.jpg|100px|center]] |

||

| {{dts|-163|format=hide}} {{c.|163 BC}} |

|||

| 163 Ք․ա․ |

|||

| |

| According to [[s:Translation:1 Maccabees#6:46|1 Maccabees 6:46]], the brother of [[Judas Maccabeus]] thrust his spear in battle into the belly of a king's [[war elephant]], which collapsed and fell on top of Eleazar, killing him instantly.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://visual.ly/funniest-and-weirdest-ways-people-have-actually-died |title=The Funniest And Weirdest Ways People Have Actually Died –|website=visual.ly|url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170430104042/http://visual.ly/funniest-and-weirdest-ways-people-have-actually-died |archive-date=30 April 2017}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope="row" |[[Manius Aquillius (consul 101 BC)|Manius Aquillius]] and [[Marcus Licinius Crassus]] |

|||

!scope="row" |Մանիուս Ակվիլիուս և [[Մարկոս Կրասսոս]] |

|||

|[[File:Roma,_denario_di_manius_aquililius,_109-108_ac_ca.JPG|center|102x102px]][[File:Late_Roman_Republic_bust_in_the_Glyptothek,_Copenhagen.jpg|center|122x122px]] |

|[[File:Roma,_denario_di_manius_aquililius,_109-108_ac_ca.JPG|center|102x102px]][[File:Late_Roman_Republic_bust_in_the_Glyptothek,_Copenhagen.jpg|center|122x122px]] |

||

| {{dts|-1|format=hide}} 1st Century BC |

|||

| Ք․ա․ 1-ին դար |

|||

| The late Roman Republic-era consul was sent as ambassador to Asia Minor in 90 BC to restore [[Nicomedes IV of Bithynia]] to his kingdom after the latter was expelled by [[Mithridates VI of Pontus]]. But Aquillius encouraged Nicomedes to raid part of Mithridates' territory, which started the [[First Mithridatic War]]. Aquillius was captured and brought to Mithridates, who in 88 BC had him executed by pouring molten gold down his throat. According to one story, [[Marcus Licinius Crassus]], a Roman general and statesman, who was very greedy despite being called "the richest man in Rome," was executed in the same manner by the [[Parthians]] after they defeated him in the [[Battle of Carrhae]] in 53 BC, in symbolic mockery of his thirst for wealth. However, it has been disputed as to whether this is how Crassus met his end.<ref>Mayor, Adrienne. The Poison King The Life and Legend of Mithridates. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp. 166-171. | Dio, Cassius. Roman History, Vol. 40, p. 27. Reproduced in Vol. III of the Loeb Classical Library edition. 1914.</ref> |

| The late Roman Republic-era consul was sent as ambassador to Asia Minor in 90 BC to restore [[Nicomedes IV of Bithynia]] to his kingdom after the latter was expelled by [[Mithridates VI of Pontus]]. But Aquillius encouraged Nicomedes to raid part of Mithridates' territory, which started the [[First Mithridatic War]]. Aquillius was captured and brought to Mithridates, who in 88 BC had him executed by pouring molten gold down his throat. According to one story, [[Marcus Licinius Crassus]], a Roman general and statesman, who was very greedy despite being called "the richest man in Rome," was executed in the same manner by the [[Parthians]] after they defeated him in the [[Battle of Carrhae]] in 53 BC, in symbolic mockery of his thirst for wealth. However, it has been disputed as to whether this is how Crassus met his end.<ref>Mayor, Adrienne. The Poison King The Life and Legend of Mithridates. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp. 166-171. | Dio, Cassius. Roman History, Vol. 40, p. 27. Reproduced in Vol. III of the Loeb Classical Library edition. 1914.</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

08:35, 26 հունվարի 2024-ի տարբերակ

Անսովոր մահերի այս ցանկը ներառում է մահվան եզակի կամ չափազանց հազվադեպ հանգամանքներ, որոնք գրանցվել են պատմության ընթացքում և նշվում են որպես անսովոր բազմաթիվ աղբյուրների կողմից:

Անսովոր մահեր

Անտիկ դարաշրջան

Այս պատմություններից շատերը հավանաբար ապոկրիֆ են:

| Անձի անունը | Պատկեր | Մահվան ամսաթիվ | Մանրամասներ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Մենես | 3200 Ք․ա․ | Եգիպտական փարավոնը և Վերին և Ստորին Եգիպտոսի միավորողը առևանգվել է, այնուհետև սպանվել գետաձիի կողմից[2][3]։ | |

| Աթենքի Դրակոն | 620 Ք․ա | Հաղորդվում է, որ աթենացի օրենսդիրը խեղդվել է Հունաստանի Էգինա քաղաքի թատրոններից մեկում, երբ երախտագետ քաղաքացիները որպես նվերներ նրան ողողել են թիկնոցներով և գլխարկներով[4][5]։ | |

| Խարոնդաս |  |

700 Ք․ա․ | Ըստ Դիոդորոս Սիկիլացու՝ Սիցիլիայից ժամանած հույն օրենսդիրը օրենք է ընդունել, ըստ որի՝ յուրաքանչյուր ոք, ով զենք է մտցնում Համագումար, պետք է մահապատժի ենթարկվի։ Մի օր նա ժամանել է Համագումար՝ օգնություն խնդրելով գյուղում մի քանի ավազակների հետ կռվելու համար, բայց դանակը դեռ ամրացված էր իր գոտուն: Սեփական օրենքը պահպանելու համար նա ինքնասպան է եղել[6][7][8]։ |

| Ֆիգալիայի Արրիխիոն |  |

564 Ք․ա․ | Հույն պանկրատիստը Օլիմպիական խաղերի եզրափակչի ժամանակ սեփական մահվան պատճառ է դարձել։ Բռնվելով իր անհայտ հակառակորդի կողմից խեղդամահի մեջ և չկարողանալով ազատվել՝ Արրիխիոնը ոտքով հարվածել է մրցակցին՝ ոտնաթաթի/կոճի վնասվածքից այնքան ցավ պատճառելով նրան, որ մրցակիցը պարտության նշան է արել մրցավարներին, բայց միևնույն ժամանակ կոտրել է Արիխիոնի վիզը։ Քանի որ հակառակորդը ընդունել էր պարտությունը, Արրիխիոնը հետմահու հաղթող է հռչակվել[9][10]։ |

| Կրոտոնի Միլո |  |

600՝ Ք․ա․ 6-րդ դար | Հաղորդվում է, որ օլիմպիական չեմպիոն ըմբիշի ձեռքերը հայտնվել են թակարդում, երբ նա փորձել է երկու կես անել ծառը. այնուհետև նրան խժռել են գայլերը (կամ, ավելի ուշ տարբերակներում, առյուծները)[11]։ |

| Զևքսիս |  |

500՝ Ք․ա․ 5-րդ դար | Հույն նկարիչը մահացել է ծիծաղից նկարելիս տարեց կնոջ[12][13]։ |

| Սամոսի Պյութագորաս |  |

495 Ք․ա․ | Անտիկ աղբյուրները համաձայն չեն, թե ինչպես է հույն փիլիսոփան մահացել[14][15], բայց մեկ ուշ և, հավանաբար, ապոկրիֆ լեգենդ, որը հաղորդում է և՛ Դիոգենես Լայերտացին՝ մ.թ.ա․ երրորդ դարի հայտնի փիլիսոփաների կենսագիր, և՛ Յամբլիքոսը՝ նեոպլատոնիստ փիլիսոփա, ասում է, որ Պյութագորասը սպանվել է իր քաղաքական թշնամիների կողմից: Ենթադրաբար, նա գրեթե կարողացել է փախչել նրանցից, բայց նա հասել է լոբու դաշտ և հրաժարվել վազել այնտեղով, քանի որ արգելել էր լոբիները որպես ծիսական անմաքուր[15][16]: Քանի որ դաշտով վազելը կխախտեր իր իսկ ուսմունքները, Պյութագորասը պարզապես դադարեց վազել և սպանվեց: Այս պատմությունը կարող է հորինված լինել Կիզիկոսի Նեանտեսի կողմից, որի վրա և՛ Դիոգենեսը, և՛ Յամբլիքոսը հիմնվում են որպես աղբյուր[15]։ |

| Անակրեոն |  |

485 Ք․ա․ | Բանաստեղծը, որը հայտնի է գինին փառաբանող գործերով, ըստ Պլինիոս Ավագի, խեղդվել է խաղողի կորիզից: 1911 թվականի «Բրիտանական հանրագիտարանը» առաջարկում է, որ «պատմությունն առասպելական հարմարեցման մթնոլորտ ունի բանաստեղծի սովորություններին»[12][17]։ |

| Հերակլիտոս Եփեսացի |  |

475 Ք․ա․ | Համաձայն Դիոգենես Լայերտացու կողմից տրված մի պատմության՝ ասվում էր, որ հույն փիլիսոփային հոշոտել են շները այն բանից հետո, երբ նա իր ջրգողությունը բուժելու համար իր վրա կովի գոմաղբ է քսել[18][19]։ |

| Թեմիոստոկլես |  |

459 Ք․ա․ | Աթենացի գեներալը, ով հաղթել է Սալամինի ճակատամարտում, իրականում մահացել է աքսորում՝ բնական պատճառներով[20][21], սակայն լայնորեն խոսվում էր, որ նա ինքնասպան է եղել՝ խմելով մանրացված հանքանյութերի լուծույթ, որը հայտնի է որպես ցլի արյուն[20][21][22][23]։ Լեգենդը լայնորեն վերապատմվում է դասական աղբյուրներում։ 20-րդ դարի սկզբերի անգլիացի կլասիցիստ Պերսի Գարդներն առաջարկել է, որ Թեմիստոկլեսի՝ ցլի արյուն խմելու մասին պատմությունը կարող էր հիմնված լինել նրա արձանի անտեղյակ թյուրըմբռնման վրա, որը ցույց էր տալիս Թեմիստոկլեսին հերոսական դիրքով, ով բարձրացրել է գավաթը որպես ընծա աստվածներին: Կատակերգական դրամատուրգ Արիստոֆանեսն իր «Ասպետները» կատակերգության մեջ (կատարված մ.թ.ա. 424 թվականին) նշում է Թեմիստոկլեսի ցլի արյուն խմելը որպես մարդու մահվան ամենահերոսական միջոց[21][24]։ |

| Էքսիլես |  |

455 Ք․ա․ | Ըստ Վալերիուս Մաքսիմուսի՝ աթենացի երեք մեծ ողբերգականներից ավագը, սպանվել է կրիայի կողմից, որը իր վրա է նետել արծիվը, որը նրա ճաղատ գլուխը շփոթել էր քարի հետ, որը հարմար էր սողունի պատյանը կոտրելու համար: Պլինիոս Ավագն իր «Բնական պատմության» մեջ ավելացնում է, որ Էսքիլեսը դրսում էր մնում՝ կանխելու այն մարգարեությունը, որ նա սպանվելու էր այդ օրը «տան ընկնելու պատճառով»[12][25][26][27]։ |

| Empedocles of Akragas |  |

-430 Կաղապար:C. | According to Diogenes Laërtius, the Pre-Socratic philosopher from Sicily, who, in one of his surviving poems, declared himself to have become a "divine being... no longer mortal",[28] tried to prove he was an immortal god by leaping into Mount Etna, an active volcano.[29][30] This legend is also alluded to by the Roman poet Horace.[31] |

| Sophocles |  |

-406 Կաղապար:C. | A number of "remarkable" legends concerning the death of another of the three great Athenian tragedians, are recorded in the late antique Life of Sophocles. According to one legend, he choked to death on an unripe grape. Another says that he died of joy after hearing that his last play had been successful. A third account reports that he died of suffocation, after reading aloud a lengthy monologue from the end of his play Antigone, without pausing to take a breath for punctuation.[27] |

| Mithridates | -401 | The Persian soldier who embarrassed his king, Artaxerxes II, by boasting of killing his rival, Cyrus the Younger (who was the brother of Artaxerxes II), was executed by scaphism. The king's physician, Ctesias, reported that Mithridates survived the insect torture for 17 days.[32][33] | |

| Democritus of Abdera |  |

-370 Կաղապար:C. | According to Diogenes Laërtius, the Greek Atomist philosopher died aged 109; as he was on his deathbed, his sister was greatly worried because she needed to fulfill her religious obligations to the goddess Artemis in the approaching three-day Thesmophoria festival. Democritus told her to place a loaf of warm bread under his nose, and was able to survive for the three days of the festival by sniffing it. He died immediately after the festival was over.[34][35] |

| Antiphanes | -310 Կաղապար:C. | According to the Suda, the renowned comic poet of the Middle Attic comedy died after being struck by a pear.[36][37] | |

| Agathocles of Syracuse |  |

-289 | The Greek tyrant of Syracuse was murdered with a poisoned toothpick.[12][38] |

| Philitas of Cos |  |

-270 Կաղապար:C. | The Greek intellectual is said by Athenaeus to have studied arguments and erroneous word usage so intensely, that he wasted away and starved to death.[39] British classicist Alan Cameron speculates that Philitas died from a wasting disease which his contemporaries joked was caused by his pedantry.[40] |

| Zeno of Citium |  |

-270 Կաղապար:C. | The Greek philosopher from Citium (Kition), Cyprus, tripped and fell as he was leaving the school, breaking his toe. Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe, "I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?" He died on the spot through holding his breath.[41] |

| Qin Shi Huang |  |

Օգոստոսի -210 | The first emperor of China, whose artifacts and treasures include the Terracotta Army, died after ingesting several pills of mercury, in the belief that it would grant him eternal life.[42][43][44] |

| Chrysippus of Soli |  |

-206 Կաղապար:C. | One ancient account of the death of the third-century BC Greek Stoic philosopher, tells that he died of laughter after he saw a donkey eating his figs; he told a slave to give the donkey neat wine to drink with which to wash them down, and then, "...having laughed too much, he died" (Diogenes Laërtius 7.185).[45] |

| Eleazar Avaran |  |

-163 Կաղապար:C. | According to 1 Maccabees 6:46, the brother of Judas Maccabeus thrust his spear in battle into the belly of a king's war elephant, which collapsed and fell on top of Eleazar, killing him instantly.[46] |

| Manius Aquillius and Marcus Licinius Crassus |   |

-1 1st Century BC | The late Roman Republic-era consul was sent as ambassador to Asia Minor in 90 BC to restore Nicomedes IV of Bithynia to his kingdom after the latter was expelled by Mithridates VI of Pontus. But Aquillius encouraged Nicomedes to raid part of Mithridates' territory, which started the First Mithridatic War. Aquillius was captured and brought to Mithridates, who in 88 BC had him executed by pouring molten gold down his throat. According to one story, Marcus Licinius Crassus, a Roman general and statesman, who was very greedy despite being called "the richest man in Rome," was executed in the same manner by the Parthians after they defeated him in the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, in symbolic mockery of his thirst for wealth. However, it has been disputed as to whether this is how Crassus met his end.[47] |

| Porcia Catonis |  |

Հունիսի -43 June 43 BC to October 42 BC | The daughter of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis and second wife of Marcus Junius Brutus, according to ancient historians such as Cassius Dio and Appian, killed herself by swallowing hot coals.[48] Modern historians find this tale implausible.[49] |

| Claudius Drusus |  |

20 Կաղապար:C. | According to Suetonius, the eldest son of the future Roman emperor Claudius, died while playing with a pear. Having tossed the pear high in the air, he caught it in his mouth when it came back, but he choked on it, dying of asphyxia.[50] |

| Tiberius |  |

Մարտի 16, 37 | The Roman emperor died in Misenum aged 78. According to Tacitus, the emperor appeared to have died and Caligula, who was at Tiberius' villa, was being congratulated on his succession to the empire, when news arrived that the emperor had revived and was recovering his faculties. Those who had moments before recognized Caligula as Augustus fled in fear of the emperor's wrath, while Macro, a prefect of the Praetorian Guard, took advantage of the chaos to have Tiberius smothered with his own bedclothes, definitively killing him.[51] |

| Simon Peter |  |

1 Between 64 and 68 AD | The apostle of Jesus was crucified upside-down in Rome, based on his claim of being unworthy to die in the same way as his Saviour.[52][53] |

| Simon the Zealot |  |

1 1st century AD | According to an ancient tradition, the apostle of Jesus, was sawn in half in Persia.[54] |

| Saint Lawrence | 258 | The deacon was roasted alive on a giant grill during the persecution of Valerian.[55][56] Prudentius tells that he joked with his tormentors, "Turn me over—I'm done on this side".[57] He is now the patron saint of cooks, chefs, and comedians.[58] | |

| Marcus of Arethusa |  |

362 | The Christian bishop and martyr was hung up in a honey-smeared basket for bees to sting him to death.[12] |

| Valentinian I |  |

17 November 375 | The Roman emperor suffered a stroke which was provoked by yelling at foreign envoys in anger.[59] |

Ծանոթագրություններ

- ↑ Hoff, Ursula (1937). «Meditation in Solitude». Journal of the Warburg Institute. 1 (44): 292–294. doi:10.2307/749994. JSTOR 749994. S2CID 192234608.

- ↑ Elder, Edward (1849), «Menes», in Smith, William (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, vol. 2, Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown.

- ↑ Manetho, The Fragments of the Aegyptiaca, Book I

- ↑ Suidas. "Δράκων Արխիվացված 3 Նոյեմբեր 2015 Wayback Machine", Suda On Line, Adler number delta, 1495.

- ↑ Felton, Bruce; Fowler, Mark (1985). «Most Unusual Death». Felton & Fowler's Best, Worst, and Most Unusual. Random House. էջ 161. ISBN 978-0-517-46297-3.

- ↑ Murray, Alexander (2007). Suicide in the Middle Ages: Volume 2: The Curse on Self-Murder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. էջ 128. ISBN 978-0-19-820731-3 – via Google Books.

- ↑ McGlew, James F. (1993). Tyranny and Political Culture in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, New York and London, England: Cornell University Press. էջեր 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8014-8387-5 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Groebner, Valentin (2002) [2000]. Carras, Ruth Mazo; Peters, Edward (eds.). Liquid Assets, Dangerous Gifts: Presents and Politics at the End of the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages Series. Translated by Selwyn, Pamela E. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. էջ 131. ISBN 978-0-8122-3650-7 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Matlock, Brett; Matlock, Jesse (2011). The Salt Lake Loonie. University of Regina Press. էջ 81.

- ↑ Gardiner, EN (1906). «The Journal of Hellenic Studies». Nature. 124 (3117): 121. Bibcode:1929Natur.124..121.. doi:10.1038/124121a0. S2CID 4090345. «Fatal accidents did occur as in the case of Arrhichion, but they were very rare...»

- ↑ Copeland, Cody (10 February 2021). «The Bizarre Death Of Milo Of Croton». Grunge.com. Վերցված է 3 January 2022-ին. «Milo of Croton's death was bizarre, but fitting»

- ↑ 12,0 12,1 12,2 12,3 12,4 Marvin, Frederic Rowland (1900). The Last Words (Real and Traditional) of Distinguished Men and Women. Troy, New York: C. A. Brewster & Co. Վերցված է 5 January 2022-ին – via Google Books. «To some of the most distinguished of our race death has come in the strangest possible way, and so grotesquely as to subtract greatly from the dignity of the sorrow it must certainly have occasioned.»

- ↑ Bark, Julianna (2007–2008). "The Spectacular Self: Jean-Etienne Liotard's Self-Portrait Laughing".

- ↑ Burkert, Walter (1972). Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. էջ 117. ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1 – via Google Books.

- ↑ 15,0 15,1 15,2 Simoons, Frederick J. (1998). Plants of Life, Plants of Death. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. էջեր 225–228. ISBN 978-0-299-15904-7 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Zhmud, Leonid (2012). Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans. Translated by Windle, Kevin; Ireland, Rosh. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. էջեր 137, 200. ISBN 978-0-19-928931-8 – via Google Books.

- ↑ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Anacreon». Encyclopædia Britannica (անգլերեն). Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. էջեր 906–907.

- ↑ Fairweather, Janet (1973). «Death of Heraclitus». էջ 2. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 6 November 2017-ին.

- ↑ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). «Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths §[[:Կաղապար:Nnbsp]]6». The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. էջ 111. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 29 August 2016-ին. «Heracl[t]ius, the Ephesian, fell into a dropsy, and was thereupon advised by the physicians to anoint himself all over with cow‑dung, and so to sit in the warm sun; his servant had left him alone, and the dogs, supposing him to be a wild beast, fell upon him, and killed him.»

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (օգնություն) - ↑ 20,0 20,1 Thucydides I, 138 Արխիվացված 5 Ապրիլ 2008 Wayback Machine

- ↑ 21,0 21,1 21,2 Marr, John (October 1995). «The Death of Themistocles». Greece & Rome. 42 (2): 159–167. doi:10.1017/S0017383500025614. JSTOR 643228. S2CID 162862935.

- ↑ Plutarch Themistocles, 31 Արխիվացված 3 Մարտ 2008 Wayback Machine

- ↑ Diodorus XI, 58 Արխիվացված 24 Սեպտեմբեր 2008 Wayback Machine

- ↑ Aristophanes 84–85 Արխիվացված 11 Հունիս 2015 Wayback Machine

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, «chapter 3», Naturalis Historiæ, vol. Book X

- ↑ La tortue d'Eschyle et autres morts stupides de l'Histoire, Editions Les Arènes, 2012, ISBN 978-2352042211

- ↑ 27,0 27,1 McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. էջեր 136–137. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3.

- ↑ Gregory, Andrew (2013). The Presocratics and the Supernatural: Magic, Philosophy and Science in Early Greece. New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury Academic. էջ 178. ISBN 978-1-4725-0416-6.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 69 Արխիվացված 5 Հունվար 2017 Wayback Machine

- ↑ Meyer, T. H. (2016). Barefoot Through Burning Lava: On Sicily, the Island of Cain – An Esoteric Travelogue (անգլերեն). Temple Lodge Publishing. ISBN 978-1906999940. Վերցված է 11 September 2017-ին.

- ↑ Horace, Ars Poetica, 465–466

- ↑ Frater, Jamie (2010). «10 truly bizarre deaths». Listverse.Com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists. Ulysses Press. էջեր 12–14. ISBN 978-1-56975-817-5.

- ↑ J. C. McKeown (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford University Press. էջ 102. ISBN 978-0-19-998212-7. «Ctesias, the Greek physician to Artaxerxes, the king of Persia, gives an appallingly detailed description of the execution inflicted on a soldier named Mithridates, who was misguided enough to claim the credit for killing the king's brother, Cyrus...»

- ↑ McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. էջ 157. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, ix.43 Արխիվացված 5 Հունվար 2017 Wayback Machine

- ↑ Suda α 2735

- ↑ Baldi, Dino (2010). Morti favolose degli antichi (իտալերեն). Macerata: Quodlibet. էջ 50. ISBN 978-8874623372.

- ↑ Hubbell, Sue (Jan 1, 1997). «Let Us Now Praise the Romantic, Artful, Versatile Toothpick». Smithsonian.

- ↑ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, 9.401e.

- ↑ Cameron, Alan (1991). «How thin was Philitas?». The Classical Quarterly. 41 (2): 534–538. doi:10.1017/S0009838800004717. S2CID 170699258.

- ↑ Laërtius, 1925, § 28

- ↑ Wright, David Curtis (2001). The History of China. Greenwood Publishing Group. էջ 49. ISBN 978-0-313-30940-3.

- ↑ Dawson, Raymond, ed. (2007). The First Emperor. Oxford University Press. էջեր 82, 150. ISBN 978-0-19-152763-0.

- ↑ Hopper, Nate (4 February 2013). «Royalty and their Strange Deaths». Esquire. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 19 November 2013-ին.

- ↑ Laertius, Diogenes (1965). Lives, Teachings and Sayings of the Eminent Philosophers, with an English translation by R.D. Hicks. Cambridge, Mass/London: Harvard UP/W. Heinemann Ltd.

- ↑ «The Funniest And Weirdest Ways People Have Actually Died –». visual.ly. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 30 April 2017-ին.

- ↑ Mayor, Adrienne. The Poison King The Life and Legend of Mithridates. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp. 166-171. | Dio, Cassius. Roman History, Vol. 40, p. 27. Reproduced in Vol. III of the Loeb Classical Library edition. 1914.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, xlvii 49. Appian, Bellum Civile iv 136.

- ↑ Church, Alfred J. (1883). Roman Life in the Days of Cicero. London: Seeley, Jackson, & Halliday.

- ↑ Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars.

- ↑ «LacusCurtius • Tacitus, Annals – Book VI Chapters 28–51». penelope.uchicago.edu. Վերցված է 30 May 2019-ին.

- ↑ Granger Ryan & Helmut Ripperger, The Golden Legend Of Jacobus De Voragine Part One, 1941.

- ↑ Cossetta, Erin (12 April 2021). «Here's What An Upside Down Cross Really Means». Thought Catalog. Վերցված է 15 August 2021-ին.

- ↑ Il Grande Dizionario dei Santi e dei Beati (իտալերեն). Vol. 4. Rome: Finegil Editoriale/Federico Motta Editore. 2006. էջեր 217–218.

- ↑ Catholic Online. «St. Lawrence – Martyr». Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 4 January 2018-ին.

- ↑ «Saint Lawrence of Rome». CatholicSaints.Info. 26 October 2008. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 14 February 2015-ին.

- ↑ Nigel Jonathan Spivey (2001), Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude, University of California Press, էջ 42, ISBN 978-0-520-23022-4

- ↑ Cayne, Bernard S. (1981), The Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 17, Grolier, էջ 85, ISBN 978-0-7172-0112-9

- ↑ Lenski, Noel (2014). Failure of Empire. University of California Press. էջ 142.

Մեջբերված գրականություն

- Barber, Richard; Barker, Juliet (1989). Tournaments: Jousts, Chivalry and Pageants in the Middle Ages. Boydell. էջեր 134, 139. ISBN 978-0-85115-470-1.

- Baumgartner, Frederic J (1988). Henry II, King of France, 1547–1559. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822307952.

- Կաղապար:Cite LotEP

- Hollister, C. Warren (2003). Frost, Amanda Clark (ed.). Henry I. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-3000-9829-7.

- Weeks, David; Gorman, Robert (2015). «15: Fans». Death at the Ballpark: More Than 2,000 Game-Related Fatalities of Players, Other Personnel and Spectators in Amateur and Professional Baseball, 1862–2014 (2nd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 9780786479320. Վերցված է 30 September 2022-ին.

- Wellman, Kathleen (2013). Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France. Yale University Press.

Հավելյալ գրականություն

- Winterbotham, Russell R. (1929). Curious and Unusual Deaths. Haldeman-Julius, Girard, Kansas.

- Powell, Michael (2008). Curious Events in History. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4027-6307-6.

- Daws, Nick (2005). Daft Deaths and Famous Last Words. Lagoon Books. ISBN 978-1-9047-9715-9.

- Dreher, Dale. ebook Death by Misadventure: 210 Dumb Ways to Die.

- Southwell, David; Twist, Sean (2007). Mysterious Deaths and Disappearances. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4042-1081-3.

- John Dunning Strange Deaths (true crime)

- Sieveking, Paul; Simmons, Ian; Stevenson, Val (2000). Strange Deaths: More Than 375 Freakish Fatalities. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. էջ 14. ISBN 978-0-7607-1947-3. Վերցված է 4 January 2022-ին – via Google Books.

- Bellamy, John G (2008). Strange Inhuman Deaths. History Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-7509-3864-8.

- Sieveking, Paul (2011). The Fortean Times Book of Strange Deaths. Russell Blackman. ISBN 978-1-907779-97-8.

- Sieveking, Paul (1998). The Fortean Times Book of More Strange Deaths. John Brown. ISBN 978-1-902212-02-9.

Արտաքին հղումներ

- Curious and Unusual Deaths Pictures. Discovery Channel.

- Freakish Fatalities Snopes.com