Մասնակից:Argam Forbes/Ավազարկղ E

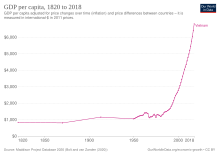

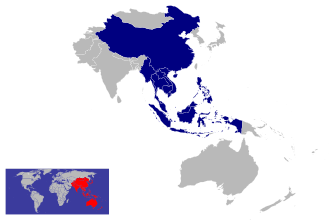

Վիետնամի տնտեսությունը զարգացող խառը սոցիալիստական ուղղվածություն ունեցող շուկայական տնտեսություն է[1]: Այն աշխարհում մեծությամբ 35-րդն է անվանական համախառն ներքին արդյունքով (ՀՆԱ) և 26-րդը՝ գնողունակության համարժեքությամբ (ՊՄԳ): Այն ցածր-միջին եկամուտ ունեցող երկիր է, որն ունի ցածր ծախսեր: Վիետնամը Ասիա-խաղաղօվկիանոսյան տնտեսական համագործակցության, Հարավարևելյան Ասիայի երկրների ասոցիացիայի և Առևտրի համաշխարհային կազմակերպության անդամ է:

1980-ականների կեսերից՝ Դոյ Մոյի բարեփոխումների ժամանակաշրջանի ընթացքում, Վիետնամը անցում է կատարել խիստ կենտրոնացված պլանային տնտեսությունից դեպի խառը տնտեսություն: Նախկինում Հարավային Վիետնամը կախված է եղել ԱՄՆ-ի օգնությունից[2], մինչդեռ Հյուսիսային Վիետնամը և վերամիավորված Վիետնամը հենվել են կոմունիստների օգնության վրա մինչև Խորհրդային Միության փլուզումը[3]:

Տնտեսությունն օգտագործում է ինչպես հրահանգային, այնպես էլ ցուցիչ պլանավորում՝ հնգամյա պլանների միջոցով՝ բաց շուկայական տնտեսության աջակցությամբ: Այդ ընթացքում տնտեսությունը բուռն աճ է գրանցել։ 21-րդ դարում Վիետնամը գտնվում է համաշխարհային տնտեսության մեջ ինտեգրվելու ժամանակաշրջանում։ Վիետնամական գրեթե բոլոր ձեռնարկությունները փոքր և միջին ձեռնարկություններ են: Վիետնամը դարձել է գյուղատնտեսական արտադրանքի առաջատար արտահանող և ծառայել է որպես օտարերկրյա ներդրումների գրավիչ ուղղություն Հարավարևելյան Ասիայում:

2017 թվականի փետրվարին PricewaterhouseCoopers-ի կանխատեսման համաձայն՝ Վիետնամը կարող է լինել աշխարհի ամենաարագ զարգացող տնտեսություններից՝ ՀՆԱ-ի տարեկան աճի պոտենցիալ տեմպերով մոտ 5,1 տոկոս, ինչը նրա տնտեսությունը կարող է դարձնել 10-րդ հորիզոնականում՝ 2050 թվականին[4]։ Վիետնամը նույնպես դասվել է այսպես կոչված Next Eleven և CIVETS երկրների շարքում:

Պատմություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Մինչև 1858 թվականը[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Վիետնամի քաղաքակրթությունը կառուցվել է գյուղատնտեսության վրա: Ֆեոդալական դինաստիաները միշտ գյուղատնտեսությունը համարում էին որպես հիմնական տնտեսական հիմք և նրանց տնտեսական մտքերը հիմնված էին ֆիզիոկրատիայի վրա: Հողատարածքների սեփականությունը կարգավորվում էր և Կարմիր գետի դելտայում կառուցվեցին այնպիսի լայնածավալ աշխատանքներ, ինչպիսիք են դամբերը՝ բրնձի թաց մշակումը հեշտացնելու համար։ Խաղաղ ժամանակներում զինվորներին ուղարկում էին տուն՝ ֆերմերային աշխատանք կատարելու։ Ավելին դատարանն արգելեց ջրային գոմեշի և խոշոր եղջերավոր անասունների մորթումը և անցկացրեց գյուղատնտեսության հետ կապված բազմաթիվ արարողություններ: Արհեստներն ու արվեստը գնահատվում էին, բայց առևտուրը հնացած էր, իսկ գործարարներին անվանում էին նվաստացուցիչ con buôn տերմինով։ Թանգ Լոնգը (Հանոյ) երկրի գլխավոր արհեստագործական կենտրոնն էր։ Չինացիները նշել են, որ վիետնամցիները բիզնես են անում ճիշտ այնպես, ինչպես չինական Սոնգ դինաստիայում[5]: 9-13-րդ դարերից վիետնամցիները կերամիկայի և մետաքսի առևտուր էին անում տարածաշրջանային տերությունների հետ, ինչպիսիք են Չինաստանը, Չամպան, Արևմտյան Սիան, Ջավան և այլն[6]: Լրացուցիչ հնագիտական ապացույցները ցույց են տվել, որ մահմեդական առևտրականները ապրել են Հանոյում մոտավորապես 9-10-րդ դարերում՝ հիմնվելով Հանոյի Հին թաղամասում հայտնաբերված մահմեդական կերամիկայի վրա[7]:

Այնուամենայնիվ 16-րդ դարից կոնֆուցիականությունը կորցրել է իր ազդեցությունը վիետնամական հասարակության վրա և սկսեց զարգանալ դրամավարկային նախակապիտալիզմի տնտեսությունը: Լի-Մակ ժամանակաշրջանում պետությունը խրախուսում էր կիսաարդյունաբերական բիզնեսը և ծովային առևտրականներին, քանի որ վիետնամական տնտեսությունը հիմնականում կախված է եղել նրանցից հաջորդ 250 տարիների ընթացքում[8]: Քաղաքները, ինչպիսիք են Դոնգ Կինը, Հի Անը և այլն, արագ աճեցին արագ ուրբանիզացիայի պայմաններում: Հետագայում նրանք դադարեցին զարգանալ, երբ օտար երկրները ընկալեցին դրանք որպես տնտեսական սպառնալիք[9][10]:

17-րդ դարում Վիետնամի տնտեսությունը հասել էր իր գագաթնակետին, քանի որ երկիրը երրորդ ամենամեծ տնտեսական ուժն էր Արևելյան Ասիայում և Հարավարևելյան Ասիայում: 18-րդ դարի վերջին տնտեսությունը տուժեց դեպրեսիայի պատճառով մի շարք հիվանդությունների և աղետների պատճառով, ինչպիսիք են Թեյ Սոնի գյուղացիական ապստամբությունը, որը ավերեց երկիրը: 1806 թվականին Նգույան դինաստիայի նոր կայսր Գիա Լոնգը պարտադրեց «Ծովային արգելքի քաղաքականությունը», որն արգելում էր վիետնամական բոլոր արտասահմանյան բիզնեսը և արգելում արևմտյան վաճառականների մուտքը Վիետնամ: Այս քաղաքականությունը հանգեցրեց Վիետնամի տնտեսության լճացմանը 19-րդ դարի սկզբին և նպաստել, որ Վիետնամը դառնա ֆրանսիական գաղութ[11]:

1858–1975[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Մինչև 19-րդ դարի կեսերի ֆրանսիական գաղութացումը, Վիետնամի տնտեսությունը հիմնականում ագրարային էր, ապրուստի վրա հիմնված և գյուղական կողմնորոշված: Այնուամենայնիվ ֆրանսիացի գաղութարարները միտումնավոր այլ կերպ զարգացրեցին շրջանները, քանի որ ֆրանսիացիներին անհրաժեշտ էր հումք և շուկա ֆրանսիական արտադրության ապրանքների համար՝ նշելով հարավը գյուղատնտեսական արտադրության համար, քանի որ այն ավելի հարմար էր գյուղատնտեսության համար, իսկ հյուսիսը՝ արդյունաբերության համար, քանի որ բնականաբար հարուստ էր հանքանյութերով և ռեսուրսներով։ Թեև ծրագիրը ուռճացնում էր տարածաշրջանային բաժանումները, արտահանման զարգացումը` ածուխը հյուսիսից, բրինձը հարավից և ֆրանսիական արտադրության ապրանքների ներմուծումը խթանեցին ներքին առևտուրը[12]:

Տարանջատումը խեղաթյուրեց Վիետնամի հիմնական տնտեսությունը՝ չափազանց շեշտելով տարածաշրջանային տնտեսական տարբերությունները: Հարավում մինչդեռ ոռոգվող բրինձը մնում էր հիմնական կենսապահովման բերքը, ֆրանսիացիները ներմուծեցին պլանտացիոն գյուղատնտեսություն այնպիսի ապրանքներով, ինչպիսիք են թեյը, բամբակը և ծխախոտը: Գաղութային կառավարությունը զարգացրեց նաև որոշ արդյունահանող արդյունաբերություններ, ինչպիսիք են ածխի, երկաթի և գունավոր մետաղների արդյունահանումը։ Հանոյում սկսվեց նավաշինական արդյունաբերություն, կառուցվել են երկաթուղիներ, ճանապարհներ, էլեկտրակայաններ, հիդրոտեխնիկական աշխատանքներ։ Հարավում գյուղատնտեսության զարգացումը կենտրոնացած էր բրնձի մշակման վրա, իսկ ազգային մասշտաբով բրինձն ու կաուչուկը արտահանման հիմնական ապրանքներն են եղել։ Ներքին և արտաքին առևտուրը կենտրոնացած է եղել Սայգոն-Չոլոն շրջանում։ Արդյունաբերությունը հարավում հիմնականում բաղկացած էր սննդի վերամշակման գործարաններից և սպառողական ապրանքներ արտադրող գործարաններից[13]:

Երբ 1954 թվականին Հյուսիսը և Հարավը քաղաքականապես բաժանվեցին, նրանք նաև որդեգրեցին տարբեր տնտեսական գաղափարախոսություններ՝ սոցիալիզմ հյուսիսում և կապիտալիզմ հարավում: 1954-1975 թվականներին Երկրորդ Հնդկաչինական պատերազմի հետևանքով առաջացած ավերածությունները լրջորեն լարեցին տնտեսությունը: Իրավիճակը վատթարացավ երկրում 1,5 միլիոն զինվորականների և քաղաքացիական անձանց մահով և դրան հաջորդած 1 միլիոն փախստականների, ներառյալ տասնյակ հազարավոր մասնագետների, մտավորականների, տեխնիկների և հմուտ աշխատողների արտագաղթի պատճառով[14]:

| Տարի | 1956 | 1958 | 1960 | 1962 | 1964 | 1966 | 1968 | 1970 | 1972 | 1974 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Հարավային Վիետնամ | 62 | 88 | 105 | 100 | 118 | 100 | 85 | 81 | 90 | 65 |

| Հյուսիսային Վիետնամ | 40 | 50 | 51 | 68 | 59 | 60 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 65 |

1975–1997[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Կառավարության երկրորդ հնգամյա պլանը (1976–1981) ուղղված է եղել արդյունաբերության և գյուղատնտեսության ոլորտներում կայուն բարձր տարեկան աճի տեմպերին և ազգային եկամուտներին և ձգտում էր միավորել Հյուսիսը և Հարավը, սակայն նպատակները չեն հաջողվել: Տնտեսության մեջ շարունակում էր գերակշռել փոքրածավալ արտադրությունը, ցածր աշխատուժի արտադրողականությունը, նյութական և տեխնոլոգիական պակասուրդը, սննդամթերքի և սպառողական ապրանքների անբավարարությունը[15]: Ավելի համեստ Երրորդ հնգամյա պլանի (1981–85) նպատակները փոխզիջում էին գաղափարական և պրագմատիկ տարբերակով, նրանք կարևորեցին գյուղատնտեսության և արդյունաբերության զարգացումը։ Նաև ջանքեր են գործադրվել պլանավորման ապակենտրոնացման և պետական պաշտոնյաների կառավարչական հմտությունների բարելավման ուղղությամբ[15]:

1975 թվականին վերամիավորվելուց հետո Վիետնամի տնտեսությունը հանդիպեց արտադրության հսկայական դժվարությունների, առաջարկի և պահանջարկի անհավասարակշռությանը, բաշխման և շրջանառության անարդյունավետությանը, գնաճի տեմպերի աճով և պարտքի աճող խնդիրներին: Վիետնամը ժամանակակից պատմության մեջ այն քիչ երկրներից է, որը հետպատերազմյան վերակառուցման ժամանակաշրջանում տնտեսական կտրուկ վատթարացում է ապրել[16]: Խաղաղ ժամանակներում նրա տնտեսությունն ամենաաղքատներից մեկն է եղել աշխարհում և ցույց է տվել, որ ընդհանուր ազգային արտադրանքի, ինչպես նաև գյուղատնտեսական և արդյունաբերական արտադրության մեջ բացասական կամ շատ դանդաղ աճ է գրանցվել[17]: Վիետնամի համախառն ներքին արդյունքը (ՀՆԱ) 1984 թվականին գնահատվել է 18,1 միլիարդ ԱՄՆ դոլար, մեկ շնչին բաժին ընկնող եկամուտը կազմում է տարեկան 200-ից մինչև 300 ԱՄՆ դոլար: Այս միջակ տնտեսական գործունեության պատճառները ներառում են ծանր կլիմայական պայմաններ, որոնք ազդել են գյուղատնտեսական մշակաբույսերի վրա, բյուրոկրատական սխալ կառավարում, մասնավոր սեփականության վերացում, ձեռներեցների դասերի ոչնչացում հարավում և Կամբոջայի ռազմական օկուպացումը (որը հանգեցրեց վերակառուցման համար շատ անհրաժեշտ միջազգային օգնության դադարեցմանը)[18]:

1970-ականների վերջից մինչև 1990-ականների սկիզբը Վիետնամը Comecon-ի անդամ է եղել և հետևաբար, մեծապես կախված էր Խորհրդային Միության և նրա դաշնակիցների հետ առևտրից: Comecon-ի լուծարումից և իր ավանդական առևտրային գործընկերների կորստից հետո Վիետնամը ստիպված եղավ ազատականացնել առևտուրը, արժեզրկել իր փոխարժեքը՝ արտահանումն ավելացնելու համար և սկսել տնտեսական զարգացման քաղաքականություն[19]: 1975-1994 թվականներին Միացյալ Նահանգները առևտրային էմբարգո է սահմանել Վիետնամի նկատմամբ՝ արգելելով ցանկացած առևտուր 19 տարվա ընթացքում։

1986 թվականին Վիետնամը սկսեց քաղաքական և տնտեսական նորացման արշավ (Դոյ Մոյ), որը բարեփոխումներ էր իրականացնում կենտրոնացված տնտեսությունից «սոցիալիստական ուղղվածություն ունեցող շուկայական տնտեսության» անցումը հեշտացնելու համար։ Այն համատեղել է կառավարության պլանավորումը ազատ շուկայի խթանների հետ և խրախուսել մասնավոր բիզնեսների և օտարերկրյա ներդրումների, ներառյալ օտարերկրյա սեփականություն հանդիսացող ձեռնարկությունների ստեղծումը: Ավելին Վիետնամի կառավարությունն ընդգծել է բնակչության տնտեսական և սոցիալական իրավունքները զարգացնելու ժամանակ ծնելիության մակարդակի իջեցման անհրաժեշտությունը՝ իրականացնելով մի քաղաքականություն, որում սահմանափակում է յուրաքանչյուր ընտանիքի երեխաների թիվը մինչև երկու, որը կոչվում է երկու երեխաների քաղաքականություն[20]: 1990-ականների վերջերին Դոյ Մոյի օրոք սկսված բիզնեսի և գյուղատնտեսության բարեփոխումների հաջողությունն ակնհայտ է եղել: Ստեղծվել են ավելի քան 30000 մասնավոր բիզնես, տնտեսությունն աճել է տարեկան ավելի քան 7%-ով, իսկ աղքատությունը կրճատվել է գրեթե երկու անգամ[21]:

1990-ականների ընթացքում արտահանումը որոշ տարիներին աճել է 20%-ից մինչև 30%: 1999 թվականին արտահանումը կազմել է ՀՆԱ-ի 40%-ը, ինչը տպավորիչ ցուցանիշ է եղել տնտեսական ճգնաժամի պայմաններում, որը հարվածեց Ասիայի մյուս երկրներին: Վիետնամը դարձել է Առևտրի Համաշխարհային Կազմակերպության (ԱՀԿ) անդամ 2007 թվականին, որն ազատեց Վիետնամին տեքստիլ քվոտաներից, որոնք ուժի մեջ էին մտել ամբողջ աշխարհում որպես MultiFiber Arrangement (MFA) 1974 թվականին[22]: ԱԳՆ-ն սահմանափակումներ է սահմանել զարգացող երկրներից տեքստիլի ներմուծման վրա արդյունաբերական զարգացած երկրների կողմից։ Չինաստանի և ԱՀԿ մյուս անդամների համար, սակայն ԱԳՆ-ի շրջանակներում տեքստիլ քվոտաների ժամկետը սպառվել է 2004 թվականի վերջին, ինչպես համաձայնեցվել էր 1994 թվականին Ուրուգվայի առևտրային բանակցությունների փուլում[23]: 2019 թվականի ուսումնասիրությունը ցույց է տվել, որ Վիետնամի ԱՀԿ մուտքը հանգեցրել է մասնավոր ընկերությունների արտադրողականության զգալի աճի, բայց ոչ մի ազդեցություն չի ունեցել պետական ձեռնարկությունների վրա: Պետական ձեռնարկությունների բացակայության դեպքում «ընդհանուր արտադրողականության աճը մոտ 40%-ով ավելի մեծ կլիներ վիետնամական հակափաստարկային տնտեսության մեջ»[24]:

Զարգացումը 1997 թվականից[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Վիետնամի տնտեսական քաղաքականությունը 1997 թվականի ասիական ֆինանսական ճգնաժամից հետո եղել է զգուշավոր՝ շեշտը դնելով ոչ թե աճի, այլ մակրոտնտեսական կայունության վրա: Մինչ երկիրը շարժվում էր դեպի շուկայական կողմնորոշված տնտեսություն, Վիետնամի կառավարությունը դեռ շարունակում է ամուր զսպել հիմնական պետական հատվածները, ինչպիսիք են բանկային համակարգը, պետական ձեռնարկությունները և արտաքին առևտուրը[25][26]: ՀՆԱ-ի աճը 1998 թվականին ընկել է հասնլով 6%-ի, իսկ 1999 թվականին՝ 5%-ի։ 2000 թվականից ի վեր տնտեսությունը գրանցել է ՀՆԱ-ի շարունակական աճ՝ առնվազն 5%[27]:

The signing of the Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) between the United States and Vietnam on July 13, 2000, was a significant milestone. The BTA provided for "normal trade relations" (NTR) status of Vietnamese goods in the U.S. market. It was expected that access to the U.S. market would allow Vietnam to hasten its transformation into a manufacturing-based, export-oriented economy. Furthermore, it would attract foreign investment, not only from the U.S., but also from Europe, Asia and other regions.[28]

In 2001, the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam approved a 10-year economic plan that enhanced the role of the private sector, while reaffirming the primacy of the state.[29] Growth then rose to 6% to 7% between 2000 and 2002 even in the midst of the global recession, making it the world's second fastest-growing economy. At the same time, investment grew threefold and domestic savings quintupled.[30]

In 2003, the private sector accounted for more than one-quarter of all industrial output.[29] However, between 2003 and 2005, Vietnam fell dramatically in the World Economic Forum's global competitiveness report rankings, largely due to negative perceptions of the effectiveness of government institutions.[29] Official corruption is endemic, and Vietnam lags in property rights, efficient regulation of markets, and labor and financial market reforms.[29]

Vietnam had an average GDP growth of 7.1% a year from 2000 to 2004. The GDP growth was 8.4% in 2005, the second-largest in Asia, trailing only China's. The government estimated that GDP grew in 2006 by 8.17%. According to the Minister of Planning and Investment, the government targeted a GDP growth of around 8.5% in 2007.[31]

On November 7, 2006, the General Council at the World Trade Organization (WTO) approved Vietnam's accession package. On January 11, 2007, Vietnam officially became the WTO's 149th member, after 11 years of preparation, including eight years of negotiation.[32] The country's access to the WTO was intended to provide an important boost to the economy, as it ensured that the liberalizing reforms continue and created options for trade expansion. However, the accession also brought serious challenges, requiring the economy to open up to increasing foreign competition.[33][34]

Vietnam's economy continues to expand at an annual rate in excess of 7%, one of the fastest-growing in the world, but it grew from an extremely low base, as it suffered the crippling effect of the Vietnam War from the 1950s to the 1970s, the punitive embargoes of the United States and its allies, as well as the austerity measures introduced in its aftermath.[29] In 2012, the communist party was forced to apologise about the mismanagement of the economy after large numbers of SOEs went bankrupt and inflation rose. The main danger has been over the bad debt in the banks totalling to 15% and forecast growth is 5.2% for 2012 but this is also due to the global economic crisis.[35] The government has launched schemes to reform the economy, however, such as lifting foreign ownership cap from 49% and partially privatizing the country's state-owned companies that have been responsible for the recent economic downturn. By the end of 2013, the government is expected to privatize 25–50% of SOEs, only maintaining control on public services and military. The recent reforms have created a major boom in the Vietnamese stock market as confidence in the Vietnamese economy is returning.

Vietnam's current economic turmoil has given rise to question of a new period of changing political economy, however.[36] Poverty remains to be the main concern on the national performance index as of 2018. The Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) found that 28% of survey respondents cited poverty as their main problem.[37] Most respondents agreed with the statement that "[P]overty reduction is imperative to ensuring that Vietnam becomes an advanced, developed country. The percentage of the poorest Vietnamese respondents who believed that their economic situation would worsen increased from 13% in 2016 to 26% in 2017.[38] The percentage of respondents with health insurance increased from 74% in 2016 to 81% in 2017, with strongest gains in the rural population groups.[38]

In 2017, Transparency International, a non-profit that tracks graft ranked Vietnam as 113th worst out of 176 countries and regions for perceptions of corruption.[37]Կաղապար:Failed verification Several graft cases found in 2016 and 2017 led to the corruption crackdown which prosecuted many bankers, businesspeople, and government officials under charges of corruption. PAPI found that bribery at public district hospital services decreased from 17% in 2016 to 9% in 2017.[38] Reports of land seizures went down from an average of about 9% before 2013, to less than 7% in 2017. The number of respondents who believed that their land was sold at a fair market value decreased from 26% in 2014 to 21% in 2017.[38] Land-use graft and petty graft, such as police officers accepting bribes, are common. According to Ralph Jennings, Vietnam has been privatizing many of its state-owned operations to reduce corruption and increase efficiency.[39]Կաղապար:Undue weight inline

As of March 2018, Vietnam's economy continued to grow, achieving the best annual growth rate in over a decade; which has led media outlets to speculate if in the near future it could be one of the Asian tigers.[40][41]

According to DBS Bank in 2019, Vietnam's economy has the potential to grow at a pace of about 6%-6.5% by 2029. Vietnam can overpower Singapore's economy by the next decade because of its strong foreign investment inflow and productivity growth.[42] However, Vietnam has surpassed Singapore just a year later.

In the early 2020s, despite trade wars with Vietnam's major trade partners, a pandemic and the increasing trend in deglobalisation, Vietnam has still managed to become Asia's top-performing economy.[43] Since 2000, Vietnam has now managed to manufacture higher-value goods with better paying jobs due to its more highly skilled workers. These workers now produce electronics which makes up 38% (in 2020) of Vietnam's exports (compared to 14% in 2010). The country had achieved an average of 6.2% in economic growth (faster than any other country in Asia after China).[44] Foreign investment on the luxury hotels sector and resorts will rise to support the tourist industry.[45]

Տվյալներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1990–2020 (with IMF staff estimations in 2021–2027). Inflation below 5% is in green.[46]

| Year | GDP growth

(real) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Unemployment rate

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 77.7 | 121.7 | 1151.2 | 36.0 | 12.3 | n/a |

| 1991 | 5.8 | 9.7 | 85.0 | 141.1 | 1236.3 | 81.8 | 10.4 | n/a |

| 1992 | 8.7 | 12.5 | 94.5 | 179.0 | 1350.3 | 37.7 | 11.0 | n/a |

| 1993 | 8.1 | 16.7 | 104.6 | 235.0 | 1468.3 | 8.4 | 10.6 | n/a |

| 1994 | 8.8 | 20.7 | 116.2 | 286.0 | 1605.0 | 9.5 | 10.3 | n/a |

| 1995 | 9.5 | 26.4 | 130.0 | 358.7 | 1765.7 | 16.9 | 5.8 | n/a |

| 1996 | 9.3 | 31.4 | 144.8 | 419.1 | 1934.8 | 5.6 | 5.9 | n/a |

| 1997 | 8.2 | 34.1 | 159.3 | 449.3 | 2095.7 | 3.1 | 6.0 | n/a |

| 1998 | 5.8 | 34.6 | 170.3 | 448.1 | 2207.3 | 8.1 | 6.9 | n/a |

| 1999 | 4.8 | 36.4 | 181.0 | 465.2 | 2310.3 | 4.1 | 6.7 | n/a |

| 2000 | 6.8 | 39.6 | 197.6 | 498.6 | 2489.3 | -1.8 | 6.4 | 24.8 |

| 2001 | 6.9 | 41.3 | 216.0 | 513.2 | 2684.5 | -0.3 | 6.3 | 25.4 |

| 2002 | 7.1 | 44.6 | 234.9 | 546.6 | 2881.3 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 27.7 |

| 2003 | 7.3 | 50.2 | 257.1 | 610.4 | 3124.4 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 29.8 |

| 2004 | 7.8 | 62.9 | 284.6 | 757.0 | 3426.5 | 7.9 | 5.6 | 29.4 |

| 2005 | 7.5 | 73.2 | 315.7 | 873.1 | 3765.8 | 8.4 | 5.3 | 28.7 |

| 2006 | 7.0 | 84.3 | 348.1 | 996.3 | 4114.3 | 7.5 | 4.8 | 30.2 |

| 2007 | 7.1 | 98.4 | 383.0 | 1152.3 | 4484.3 | 8.3 | 4.6 | 32.2 |

| 2008 | 5.7 | 124.8 | 412.5 | 1446.6 | 4782.9 | 23.1 | 2.4 | 31.0 |

| 2009 | 5.4 | 129.0 | 437.5 | 1481.4 | 5023.9 | 6.7 | 2.9 | 36.3 |

| 2010 | 6.4 | 143.2 | 471.2 | 1628.0 | 5357.1 | 9.2 | 2.9 | 36.8 |

| 2011 | 6.4 | 171.3 | 511.9 | 1949.8 | 5826.2 | 18.7 | 2.2 | 35.8 |

| 2012 | 5.5 | 195.2 | 568.4 | 2197.6 | 6400.2 | 9.1 | 2.0 | 38.3 |

| 2013 | 5.6 | 212.7 | 607.0 | 2370.0 | 6762.7 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 41.4 |

| 2014 | 6.4 | 232.9 | 660.6 | 2566.9 | 7281.2 | 4.1 | 2.1 | 43.6 |

| 2015 | 7.0 | 236.8 | 700.3 | 2581.9 | 7635.3 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 46.1 |

| 2016 | 6.7 | 252.1 | 770.9 | 2720.2 | 8316.2 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 47.5 |

| 2017 | 6.9 | 277.1 | 851.1 | 2957.9 | 9085.6 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 46.3 |

| 2018 | 7.2 | 303.1 | 934.1 | 3201.7 | 9867.4 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 43.7 |

| 2019 | 7.2 | 327.9 | 1018.8 | 3398.2 | 10559.3 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 41.3 |

| 2020 | 2.9 | 342.9 | 1061.4 | 3520.7 | 10897.0 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 41.7 |

| 2021 | 2.6 | 366.2 | 1134.0 | 3724.5 | 11533.9 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 40.2 |

| 2022 | 7.0 | 413.8 | 1299.7 | 4162.9 | 13075.0 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 41.3 |

| 2023 | 6.2 | 469.6 | 1429.0 | 4682.8 | 14248.9 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 42.0 |

| 2024 | 6.6 | 517.6 | 1554.6 | 5118.2 | 15371.5 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 42.3 |

| 2025 | 6.7 | 569.1 | 1689.6 | 5582.5 | 16572.6 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 42.4 |

| 2026 | 6.7 | 624.4 | 1837.7 | 6078.4 | 17889.5 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 42.4 |

| 2027 | 6.8 | 682.9 | 2001.0 | 6600.2 | 19341.2 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 42.2 |

Economic sectors[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Agriculture, fishery and forestry[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

In 2003, Vietnam produced an estimated 30.7 million cubic meters of wood. Production of sawn wood was a more modest 2,950 cubic meters. In 1992, in response to dwindling forests, Vietnam imposed a ban on the export of logs and raw timber. In 1997, the ban was extended to all timber products except wooden artifacts. During the 1990s, Vietnam began to reclaim land for forests with a tree-planting program.[29]

Vietnam's fishing industry, which has abundant resources given the country's long coastline and extensive network of rivers and lakes, has generally experienced moderate growth. In 2003, the total catch was about 2.6 million tons. However, seafood exports increased fourfold between 1990 and 2002 to more than US$2 billion, driven in part by shrimp farms in the South and "catfish", which are a different species from their American counterparts, but are marketed in the United States under the same name. By selling vast quantities of shrimp and catfish to the U.S., Vietnam triggered antidumping complaints by the U.S., which imposed tariffs in the case of catfish and was considering doing the same for shrimp. In 2005, the seafood industry began to focus on domestic demand to compensate for declining exports.[29]

Vietnam is one of the top rice exporting countries in the world, but the limited sophistication of small-scale Vietnamese farmers causes quality to suffer.[47] Vietnam is also the world's second-largest exporter of coffee, trailing behind Brazil.[48]

Vietnam produced in 2018:[49]

- 44.0 million tons of rice (5th largest producer in the world, behind China, India, Indonesia and Bangladesh);

- 17.9 million tons of sugarcane (16th largest producer in the world);

- 14.8 million tons of vegetable;

- 9.8 million tons of cassava (7th largest producer in the world);

- 4.8 million tonnes of maize;

- 2.6 million tonnes of cashew nut (largest producer in the world);

- 2.0 million tons of banana (20th largest producer in the world);

- 1.6 million tons of coffee (2nd largest producer in the world, only behind Brazil);

- 1.5 million tons of coconut (6th largest producer in the world);

- 1.3 million tons of sweet potato (9th largest producer in the world);

- 1.2 million tons of watermelon;

- 1.1 million tons of natural rubber (3rd largest producer in the world, behind Thailand and Indonesia);

- 852 thousand tons of orange (18th largest producer in the world);

- 779 thousand tons of mango (including mangosteen and guava);

- 654 thousand tons of pineapple (12th largest producer in the world);

- 270 thousand tons of tea (6th largest producer in the world);

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products.[49]

In 2018, Vietnam was the world's 5th largest producer of pork (3.8 million tonnes). This year the country also produced 839 thousand tons of chicken meat, 334 thousand tons of beef, 936 million liters of cow's milk, 20 thousand tons of honey, among others.[49]

Energy, mining and minerals[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Petroleum is the main source of energy, followed by coal, which contributes about 25% of the country's energy (excluding biomass). Vietnam's oil reserves are in the range of 270–500 million tons. Oil production rose rapidly to 403,300 barrels per day (64,120 m3/d) in 2004, but output is believed to have peaked and is expected to decline gradually.

In 2003, mining and quarrying accounted for 9.4% of GDP, and the sector employed 0.7% of the workforce. Petroleum and coal are the main mineral exports. Also mined are antimony, bauxite, chromium, gold, iron, natural phosphates, tin, and zinc.[29]

In 2019, Vietnam was the 9th largest world producer of antimony;[50] 10th largest producer of tin;[51] 11th largest producer of bauxite;[52] 12th largest world producer of titanium ;[53] 13th largest world producer of manganese[54] and 9th largest producer of phosphate in the world.[55] The country is also one of the world's largest producers of ruby, sapphire, topaz and spinel.

Crude oil was Vietnam's leading export until the late 2000s, when high-tech electrical manufactures emerged to become the biggest export market (by 2014, crude oil comprised only 5% of Vietnamese exports, compared to 20% of all exports in 1996). This is in part because Vietnam crude oil peaked in 2004, when crude oil represented 22% of all export earnings.[56] Petroleum exports are in the form of crude petroleum because Vietnam has a very limited refining capacity. Vietnam's only operational refinery, a facility at Cat Hai near Ho Chi Minh City, has a capacity of only 800 barrels per day (130 m3/d). Refined petroleum accounted for 10.2% of total imports in 2002. As of 2012, Vietnam had only one refinery, the Dung Quat refinery, but a second one, the Nghi Son Refinery was planned and was scheduled for construction in May 2013.[29][57]

Vietnam's anthracite coal reserves are estimated at 3.7 billion tons. Coal production was almost 19 million tons in 2003, compared with 9.6 million tons in 1999. Vietnam's potential natural gas reserves are 1.3 trillion cubic meters. In 2002, Vietnam brought ashore 2.26 billion cubic meters of natural gas. Hydroelectric power is another source of energy. In 2004, Vietnam confirmed plans to build a nuclear power plant with Russian assistance,[29] and a second by a Japanese group.

From 2019 onwards, renewable energy deployment in Vietnam accelerated, by far surpassing the other Southeast Asian countries.[58] Most of the newly deployed renewable energy was in the form of solar and wind power plants. By 2023, however, this development had slowed down, mainly due to limited electrical grid capacity and reduced government support.[58]

Industry and manufacturing[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Although the industrial sector contributed 40.1% of GDP in 2004, it employed only 12.9% of the workforce. In 2000, 22.4% of industrial production was attributable to non-state activities. From 1994 to 2004, the industrial sector grew at an average annual rate of 10.3%. Manufacturing contributed 20.3% of GDP in 2004, while employing 10.2% of the workforce. From 1994 to 2004, manufacturing GDP grew at an average annual rate of 11.2%. The top manufacturing sectors — electronics, food processing, cigarettes and tobacco, textiles, chemicals, and footwear goods — experienced rapid growth. Benefits from its proximity to China with lower labor cost, Vietnam is becoming a new manufacturing hub in Asia, especially for Korean and Japanese firms. For instance, Samsung produces about 40% of its phones in Vietnam.[59] In the past decade, a significant automotive industry has been developed. As of 2019, Samsung employs over 200,000 employees in the Hanoi-area of Vietnam to produce smartphones, while offsourcing some manufacturing to China[60] and manufacturing large portions of its phones in India.[61][62][63][64] LG Electronics moved smartphone production to Vietnam from South Korea, in order to stay competitive. LG said that "Vietnam provides an "abundant labor force", as motivation for the move.[65]

Services and tourism[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

In 2004, services accounted for 38.2% of gross domestic product (GDP). From 1994 to 2004, GDP attributable to the service sector grew at an average annual rate of 6.0%.[29]

Tourism[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

In 2012, Vietnam welcomed 6.8 million international visitors and the number is expected to reach over 7 million in 2013. Vietnam keeps emerging as an attractive destination. In TripAdvisor's list of top 25 destinations Asia 2013 by travelers' choice, there are four cities of Vietnam, namely Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Hoi An and Ha Long.

2016 was the first year ever which Vietnam welcomed over 10 million international visitors.[66] Since then, this figure has continued to rise. In 2019, Vietnam with 18 million international visitors was fifth most visited country in the Asia-Pacific region as per World Tourism rankings released by the United Nations World Tourism Organization.[67]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnam, the country has suspended issuance of all tourist visa since March 2020, as of September 2020, the country is still closed for foreign tourists,[68] with plans to reopen for tourism from a limited number of Asian countries.[69] The country recorded a 98% year-on-year drop in foreign visitors for April 2020. With no reopening for tourists in sight, the government has called for the promotion of domestic tourism.[70] Total tourism revenues dropped by over 60% year-on-year for July 2020.[71]

Export of labour[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The export of labour, that is the sending of Vietnamese workers to work in other countries, is also key to the Vietnamese economy, with much of their earnings being sent back to Vietnam. This labour export was disrupted due to the Covid pandemic, however by 2022, Vietnam hopes to send 90,000 workers abroad. Traditional destinations have included South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, the Republic of China, and now Vietnam is aiming for Germany, Russia, and Israel.[72]

Banking and finance[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Banking[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The most important banks are the state-owned VietinBank, BIDV, and Vietcombank, which dominate the banking sector. There is also a trend of foreign investment into profitable banks. For example, VietinBank is currently owned by Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ (19.73%) while Vietcombank is owned by Mizuho (15%).

| Rank | Bank | Date of update | Authorised capital | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In VND, billions | In US dollars, billions | |||

| 1 | BIDV | December 31, 2020 | 40,220.2 | 1.73 |

| 2 | VietinBank | December 31, 2020 | 37,234.0 | 1.60 |

| 3 | Vietcombank | December 31, 2020 | 37,088.8 | 1.59 |

| 4 | Techcombank | December 31, 2020 | 35,001.4 | 1.50 |

| 5 | Agribank | December 31, 2020 | 30,709.9 | 1.32 |

(NOTE: Average exchange rates of 2020. Source: tradingeconomics.com. 1 USD = 23,286 VND)

Finance[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Vietnam has two stock trading centers, the Ho Chi Minh City Securities Trading Center and the Hanoi Securities Trading Center, which run the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HOSE) and the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX), respectively.

Currency, exchange rate and inflation[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Currency[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The currency used in Vietnam is the đồng, shortened as VND or đ.

Exchange rate[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the Vietnamese đồng is important because the dong, although not freely convertible, is loosely pegged to the dollar through an arrangement known as a "crawling peg". This mechanism allows the dollar–dong exchange rate to adjust gradually to changing market conditions.[29] As of December 5, 2018, a US dollar is worth 23,256 Vietnamese đồng.

Gold still maintains its position as a physical currency to a certain extent, although it has seen its economic role declining in recent years.[73]

Inflation[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Vietnam saw high inflation in 1980s.[74] During this period, there was excessive demand for the industrial sector development, food, and other commodities. In order to stimulate supply, government attempted co-integration of parallel and planned market. Though the initial reform[75] in the 1980s raised the total output, due to the report being partial, it also led to the CPI inflation rate being pushed to 200% in 1982. To tackle this, govt introduced forced savings which can be understood as the accumulation of unspent money to make the monetary overhang.

Vietnam's economy experienced a hyperinflation period in its early years of the extensive reform program, especially from 1987 to 1992.[76]

In 2008, inflation was tracking at 20.3% for the first half of the year,[77] higher than the 3.4% in 2000, but down significantly from 160% in 1988.[29]

In 2010, inflation stood at 11.5%, and 18.58% in 2011.[78]

At the end of 2012, inflation stood at 7.5%, a substantial decrease from 2011.[79]

In 2013, inflation stood at 6%,[80] and 4.09% in 2014.[81] In 2016, it was only 2%.

Mergers and acquisitions[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

With 1,120 inbound deals with a cumulated value of almost 15 bil. USD, there is a tremendous interest by foreign companies to get access to the Vietnamese market or continue the expansion using mergers and acquisitions. From 1991 to February 2018, Vietnamese companies were involved as either an acquiror or an acquired company in 4,000 mergers and acquisitions with a total value of 40.6 bil. USD. The mergers and acquisitions activities faced many obstacles, lowering the rate of success of the transaction. Common obstacles come from culture, transparency and legal aspects.[82] The Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances that has been active in Vietnam since 2006 and its M&A expert Christopher Kummer think that after the peak in 2016 and 2017 the trend will decrease in 2018.[83][84][85] Among the largest and most prominent transactions since 2000 are:

| Date Announced | Acquiror Name | Acquiror Nation | Target Name | Target Nation | Value of Transaction ($mil) |

| 12/19/2017 | Vietnam Beverage Co. Ltd. | Vietnam | Sabeco | Vietnam | 4,838.49 |

| 02/16/2012 | Perenco SA | France | ConocoPhilips Co-Oil&Gas Asset | Vietnam | 1,290.00 |

| 04/29/2016 | Central Group of Cos | Thailand | Casino Guichard-Perrachon-BigC | Vietnam | 1,135.33 |

| 12/25/2015 | Singha Asia Holding Pte Ltd. | Singapore | Masan Consumer Corp | Vietnam | 1,100.00 |

| 02/13/2015 | China Steel Asia Pac Hldg Pte | Singapore | Formosa Ha Tinh (Cayman) Ltd. | Vietnam | 939.00 |

| 08/07/2014 | Berli Jucker PCL | Thailand | Metro Cash & Carry Vietnam Co | Vietnam | 875.20 |

| 12/27/2012 | Bk of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd. | Japan | VietinBank | Vietnam | 742.34 |

| 04/17/2015 | TCC Land International Pte Ltd. | Singapore | Metro Cash & Carry Vietnam Co | Vietnam | 705.14 |

| 10/05/2011 | Vincom JSC | Vietnam | Vinpearl JSC | Vietnam | 649.39 |

| 01/28/2016 | Masan Grp Corp | Vietnam | Masan Consumer Corp | Vietnam | 600.00 |

All of the top 10 deals are inbound into Vietnam and none are outbound.[86]

Trade[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Economic relations with the United States are improving but are not without challenges. Although the United States and Vietnam reached a landmark bilateral agreement in December 2001, which helped increase Vietnam's exports to the United States, disagreements over textile and catfish exports are hindering full implementation of the agreement. Further disrupting the economic relations between the two countries were efforts in Congress to link non-humanitarian aid to Vietnam's human rights record. Barriers to trade and intellectual property are also within the purview of bilateral discussions.[29]

Given neighboring China's rapid economic ascendancy, Vietnam highly values its economic relationship with China. Following the resolution of most territorial disputes, trade with China is growing rapidly, and in 2004, Vietnam imported more products from China than from any other country. In November 2004, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Vietnam is a member, and China announced plans to establish the world's largest free-trade area by 2010.[29]

Vietnam became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on January 11, 2007.[29]

In December 2015, Vietnam joined the ASEAN Economic Community along with the 9 other ASEAN members. The community's goal is to integrate the 10 members of ASEAN and bring a freer flow of labor, investment and trade to the region.[87]

Currently, Vietnam is being tugged in multiple directions from multiple powers, namely, Russia, China and the U.S. in its attempts to achieve economic multilateralization.[88][89] Alternatively in the region, it is also pulled by either China, South Korea, Japan or ASEAN countries, as well as other constituents such as Taiwan & Hong Kong as well as Australia/New Zealand and India in the region (ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+6).[90]

Foreign trade[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Since Đổi Mới in 1986, Vietnam has increased trading, growing both exports and imports in double digits ever since. More recently, alarms on trade account deficits have been raised domestically, especially after joining the WTO in 2007. Throughout the next five years after 2007, Vietnam ran a trade deficit with the rest of the world in the tens of billions of dollars, with the record trade deficit in 2008 of US$18 billion.[77]

The account deficit has since decreased. In 2012, Vietnam recorded a trade surplus of US$780 million, the first trade surplus since 1993. Total trade reached US$228.13 billion, an increase of 12.1% from 2011.[91] In 2013, Vietnam recorded the second year of trade surplus of US$863 million. In 2014, Vietnam recorded the third year of trade surplus of US$2.14 billion, the largest trade surplus ever in history.[92] Three years later, in 2017, it surpassed itself with a record of $2.92 billion.

| Year | Total trade (US$ billions) | Export (US$ billions) | Export change (%) | Import (US$ billions) | Import change (%) | Account balance (US$ billions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 31.20 | 15.00 | 16.20 | -1.2 | ||

| 2002 | 36.40 | 16.70 | 11.3 | 19.70 | 21.6 | -3.0 |

| 2003 | 45.20 | 20.2 | 21.0 | 25.2 | 27.9 | -5.1 |

| 2004 | 58.50 | 26.5 | 31.2 | 32.0 | 27.0 | -5.4 |

| 2005 | 69.40 | 32.4 | 22.3 | 37.0 | 5.7 | -4.5 |

| 2006 | 84.70 | 39.8 | 22.8 | 44.9 | 21.4 | -5.1 |

| 2007 | 111.30 | 48.6 | 22.1 | 62.7 | 39.6 | -14.1 |

| 2008 | 143.40 | 62.7 | 29.0 | 80.7 | 28.7 | -18.0 |

| 2009 | 127.00 | 57.1 | -8.9 | 69.9 | -13.4 | -12.9 |

| 2010 | 157.00 | 72.2 | 26.4 | 84.8 | 21.3 | -12.6 |

| 2011 | 203.41 | 96.91 | 34.2 | 106.75 | 25.8 | -9.84[93] |

| 2012 | 228.57 | 114.57 | 18.2 | 113.79 | 6.6 | 0.780[94] |

| 2013 | 263.47 | 132.17 | 15.4 | 131.30 | 15.4 | 0.863 |

| 2014 | 298.23 | 150.19 | 13.7 | 148.04 | 12.1 | 2.14 |

| 2015 | 327.76 | 162.11 | 7.9 | 165.65 | 12 | -3.54[95] |

| 2016 | 349.20 | 175.94 | 8.6 | 173.26 | 4.6 | 2.68 |

| 2017 | 425.12 | 214.01 | 21.2 | 211.1 | 20.8 | 2.92[96] |

| 2018 | 480.17 | 243.48 | 13.2 | 236.69 | 11.1 | 6.8[97] |

| 2019 | 517.26 | 264.189 | 8.4 | 253.071 | 6.8 | 11.12[98] |

| 2020 | 545.36 | 282.65 | 7 | 262.7 | 3.7 | 19.95[99] |

Exports[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

In 2004, Vietnam's exports of merchandise were valued at US$26.5 billion, and were growing rapidly along with imports. Vietnam's principal exports were crude oil (22.1%), textiles and garments (17.1%), footwear (10.5%), fisheries products (9.4%) and electronics (4.1%). The main destinations of Vietnam's exports were the United States (18.8%), Japan (13.2%), China (10.3%), Australia (6.9%), Singapore (5.2%), Germany (4.0%), and the United Kingdom (3.8%).[29]

In 2012, export rose 18.2%, valued at US$114.57 billion.[91] Vietnam's main export market included the EU with US$20 billion, United States with US$19 billion, ASEAN with $US 17.8 billion, Japan with US$13.9 billion, China with US$14.2 billion, and South Korea with US$7 billion.[100]

In 2013, exports rose 15.4%, valued at US$132.17 billion, of which export of electronics now comprised 24.5% of total export, compared with a 4.4% in 2008. Textiles and garments are still an important part in Vietnam's export, valued about US$17.9 billion in 2013.

In 2014, exports rose 13.6%, reaching US$150.1 billion. Electronics and electronics parts, textiles and garments, computers and computer parts are the three main export groups of Vietnam. The United States continued to be Vietnam's largest export market, with US$28.5 billion. The EU is second with US$27.9 billion, ASEAN is third, China is fourth and Japan is the fifth largest export market of Vietnam.

Imports[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

In 2004, Vietnam's merchandise imports were valued at US$31.5 billion and growing rapidly. Vietnam's principal imports were machinery (17.5%), refined petroleum (11.5%), steel (8.3%), material for the textile industry (7.2%), and cloth (6.0%). The main origins of Vietnam's imports were China (13.9%), Taiwan (11.6%), Singapore (11.3%), Japan (11.1%), South Korea (10.4%), Thailand (5.8%), and Malaysia (3.8%).[29]

Vietnam import rose 6.6% in 2012, valued at US$113.79 billion.[91] Major import countries were China US$29.2 billion, ASEAN with US$22.3 billion, South Korea with US$16.2 billion, Japan with US$13.7 billion, EU with US$10 billion, and United States with US$6.3 billion.[100]

In 2014, imports rose 12.1%, reaching US$148 billion, most of which are materials and machinery needed for export. China continued to be Vietnam's largest import partner, with US$43.7 billion. The ASEAN is second with US$23.1 billion, South Korea is third, Japan is fourth and the EU is the fifth largest import partner of Vietnam.

External debt, foreign aid and foreign investment[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

In 2004, external debt amounted to US$16.6 billion, or 37% of GDP.[101][29]

From 1988 to December 2004, cumulative foreign direct investment (FDI) commitments totaled US$46 billion. By December 2004, about 58% had been dispersed. About half of FDI has been directed at the two major cities (and environs) of Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. In 2003, new foreign direct investment commitments were US$1.5 billion. The largest sector by far for licensed FDI is industry and construction. Other sectors attracting FDI are oil and gas, fisheries, construction, agriculture and forestry, transportation and communications, and hotels and tourism. From 2006 to 2010, Vietnam hoped to receive US$18 billion of FDI to support a targeted growth rate in excess of 7%. Despite rising investments, foreign investors still regard Vietnam as a risky destination, as confirmed by recent survey by the Japan External Trade Organization of Japanese companies operating in Vietnam. Many of the respondents complained about high costs of utilities, office rentals and skilled labor. Corruption, bureaucracy, lack of transparent regulations and the failure to enforce investor rights are additional obstacles to investment, according to the U.S. State Department. Vietnam tied with several nations for the 102nd place in Transparencies International's Corruption Perceptions Index in 2004.[29] A study was conducted to examine the effect foreign investment had on corruption in Vietnam. The study concluded that the propensity of foreign firms to bribe at entry is higher in restricted sectors. Also, the removal of investment restrictions leads to reductions in bribery as a result of more Foreign Investment Enterprises, and consequently more competition entering that sector.[102]

The World Bank's assistance program for Vietnam has three objectives: to support Vietnam's transition to a market economy, to enhance equitable and sustainable development and to promote good governance. From 1993 through 2004, Vietnam received pledges of US$29 billion of official development assistance (ODA), of which about US$14 billion, or 49%, has been disbursed. In 2004, international donors pledged ODA of US$2.25 billion, of which US$1.65 billion actually was disbursed. Three donors accounted for 80% of disbursements in 2004: Japan, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank. From 2006 to 2010, Vietnam hopes to receive US$14 billion to US$15 billion of ODA.[29]

Pledged foreign direct investment was US$21.3 billion for 2007 and a record US$31.6 billion for the first half of 2008.[77] Mergers and acquisitions have gradually become an important channel of investments in the economy, especially after 2005.

Free trade agreements[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA)

- ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade Area (AANZFTA) is a free trade area between ASEAN and ANZCERTA, signed on 27 February 2009[103] and coming into effect on 1 January 2010.[104] Details of the AANZFTA agreement are available online.[105]

- ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA), in effect as of 1 January 2010[106]

- ASEAN–India Free Trade Area (AIFTA), in effect as of 1 January 2010[106]

- ASEAN–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership (AJCEP)

- ASEAN–Korea Free Trade Area (AKFTA), in effect as of 1 January 2010[106]

- Comprehensive Economic Partnership for East Asia

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

- On 29 May 2015, Vietnam signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with Eurasian Economic Union.[107]

- European Union-Vietnam Free Trade Afreement (EVFTA) came into effect on 1 August 2020.

- Vietnam-Chile Free Trade Agreement (VCFTA) came into effect on 1 January 2014.[108]

- Vietnam-Korea Free Trade Agreement (VKFTA) came into effect on 20 December 2015.[109]

- Japan-Vietnam Economic Partnership Agreement came into effect on 1 October 2009.[110]

- United Kingdom-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement came into effect on 1 January 2021.[111]

Economic development strategy[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Guiding principle[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Industrialization and Modernization (IM)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

"Industrialization and modernization is a process of fundamental and all-rounded change of production, business, services and social and economic management from the predominant use of artisanal labor to a predominant use of labor power with technology, methods and ways of working that are advanced, modern and rely upon the development of industry and scientific – technical progress to create high labor productivity. So from a theoretical and practical view industrialization and modernization are a necessary historical process that Vietnam must go through change our country into an industrial country […]"

- 7th National Congress-Central Committee (1991)

Socialist-Oriented Market Economy (SOME)[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

"The nature of a socialist-oriented market economy in our country:

- It is not an economy managed according in the style of a centralized bureaucratic subsidized system

- It is not a free market capitalist economy

- It is not yet entirely a socialist-oriented economy. This is because our country is in the period of transition to socialism, and there is still a mixture of, and a struggle between, the old and the new, so there simultaneously are, and are not yet sufficiently, socialist factors"

- 7th National Congress-Central Committee (1991)

Development strategy[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Trade liberalization[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Over the past 30 years, Vietnam has signed numerous trade agreements with different partners, promoting the country as one of the main manufacturing hubs in the world. In 1995, Vietnam joined the ASEAN community. In 2000, it signed a free trade agreement with the United States, to be followed by admission to the World Trade Organisation in 2007. Since then, the country has further integrated itself into the world economy with bilateral agreements with other ASEAN countries, China, India, Japan, and Korea, to name a few. Vietnam has actively working with other partners on ratifying the Trans-Pacific Partnership to form CP TPP, or TPP-11, after the withdrawal of the US, in order to promote economic cooperation, regional connectivity and promote economic growth between member countries. The World Bank estimates that the CP TPP would help the country's GDP to grow by 1.1% by 2030 with a boost to productivity. The overall impact of these efforts was the lowering of tariffs on both imports and exports to and from Viet Nam, and an improved trade balance with a surplus of $2.8 billion during the first eight months of 2018 (Vietnam Custom Department).[112] Most recently, on June 30, 2019, Vietnam signed the Free Trade Agreement and Investment Protection Agreement with the EU after 10 years of negotiation, making it only the fourth country in Asia which managed to sign such agreement with the western bloc (after Japan, South Korea, and Singapore)

Domestic reform[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The government has made real effort in changing its mindset toward a more open market economy, lowering the cost of doing business, and putting regulation in place to ensure rights and orders. In 1986 the government passed its first Law on Foreign Investment, allowing foreign companies to operate in Vietnam. Between 1981 and 2005, Vietnam created a new intellectual property law that gradually moved away from the Soviet-style concept of collective ownership.[113] A milestone in this evolution was the Copyright Agreement that Vietnam concluded with the US in 1997, serving primarily the US interest of preventing Vietnam from becoming an international center for illegal copying.[113] The constitution has come a long way since, with the law being revised regularly to cater for a more investor-friendly business environment while aiming to reduce red-tape and accelerate foreign investment into the country. The Global Competitiveness Report[114] by World Economic Forum placed Vietnam at 55th in 2017, rising from 77th place in 2006. In the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business rankings,[115] Vietnam also rose from 104th place in 2007 to 68th place in 2017. The Bank commended Vietnam on progress made in enforcing contracts, increasing access to credit and basic infrastructure, and trading, among other factors.

Human and physical capital investment[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Vietnam invested a lot in its human capital and infrastructure. With a growing population – 96 million today, up from 60 million in 1986, and more than half are under the age of 35– Vietnam made large public investments in education, especially making primary education universal and compulsory. This was necessary, given the country's export-led growth strategy, where literacy for the mass workforce is deemed important for growth in the manufacturing sector. On the other hand, Vietnam also invested heavily in infrastructure, ensuring cheap mass access to necessities like electricity, water, and especially the internet. These two factors together helped Vietnam to become a hub for foreign investment and manufacturing in Southeast Asia. Japanese and Korean electronics companies like Samsung, LG, Olympus, and Pioneer built factories, and countless European and American apparel makers set up textile operations in the country. Intel opened a $1 billion chip factory in 2010, signalling the importance of Vietnam's strategic positioning in the eyes of the international business community.

Sustainable growth[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Economic growth in Vietnam was considered as broadly in line with other developing countries. The Inclusive Development Index[116] by WEF put Vietnam in a group of countries that have done particularly well and advancing in the ranking of the world's most inclusive economies. This has been notably evident with the role of women participating in the economy. Their labor force participation rate is within 10% of that of men, a smaller gap than many other countries according to World Bank, and in 2015 women-led households are generally not poorer than those led by men. Primary and secondary enrollment rates for boys and girls are also essentially the same, and more girls continue studying in high school than boys. The government is actively reviewing and adjusting its policy, as shown in the current official Development Strategy Action Plan 2011–2020, to develop appropriate mechanisms for a more equitable growth across the country; promoting the advantages of each regions, working in collaboration with each other to support and amplify the fruit of development.

In 2017, with the help of the United Nations, Vietnam official started the ground work to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals with the development of the "One Strategic Plan",[117] integrating the SDGs with the nation's Socio-Economic Development Strategy (2011-2020) and Socio-Economic Development Plan (2016-2020). The OSP can be used as a guideline for government agencies to implement the SDGs in the most effective ways, focusing on areas of importance, such as: investing in people, climate resilience and environmental sustainability, prosperity and partnership, justice and inclusive governance. Vietnam has also developed a National Action Plan to review current growth policies and update these to align with the interest of the SDGs. This is done in consultation with ministries, local governments, and other stakeholders so that a common framework can be set forward.

Economic indicators and international rankings[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

| Կազմակերպություն | Կոչում | Տարի | Վարկանիշ |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA (Ծրագրային դաշինք) | ՏՏ արդյունաբերության մրցունակության ինդեքս | 2011 թ | 53՝ 66-ից [118] |

| Արժույթի միջազգային հիմնադրամ | Համախառն ներքին արդյունք (ՀՄԳ) | 2020 թ | 23՝ 190-ից |

| Համաշխարհային տնտեսական ֆորում | Համաշխարհային մրցունակություն | 2019թ | 141-ից 67-ը [119] |

| Համաշխարհային Բանկ | Բիզնես վարելու հեշտություն | 2018 թ | 68՝ 190-ից |

| The Heritage Foundation / The Wall Street Journal | Տնտեսական ազատության ինդեքս | 2019թ | 128՝ 180-ից – հիմնականում ոչ ազատ (2019) [120] |

| Թրանսփարենսի Ինթերնեշնլ | Կոռուպցիայի ընկալման ինդեքս | 2019թ | 96՝ 177-ից |

Notes[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

References[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- ↑ Cling, Jean-Pierre; Razafindrakoto, Mireille; Roubaud, Francois (Spring 2013). «Is the World Bank compatible with the "Socialist-oriented market economy"?». Revue de la régulation: Capitalisme, institutions, pouvoirs (13). doi:10.4000/regulation.10081. Վերցված է 29 March 2024-ին.

- ↑ Shriek, David K. (1974-01-27). «South Vietnam, a U. S. Subsidiary». The New York Times (ամերիկյան անգլերեն). ISSN 0362-4331. Վերցված է 29 September 2023-ին.

- ↑ Prybyla, Jan S. (1966). «Soviet and Chinese Economic Aid to North Vietnam». The China Quarterly (անգլերեն). 27: 84–100. doi:10.1017/S0305741000021706. ISSN 1468-2648.

- ↑ «The World in 2050» (PDF). PricewaterhouseCoopers. Վերցված է 24 April 2017-ին.

- ↑ «On the Economic and Cultural Exchange between Song Dynasty and Li Dynasty in Vietnam» (չինարեն). Nan Yi. 18 August 2019.

- ↑ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, vol 4.

- ↑ Hoàng thành Thăng Long (8 August 2013). «10th-century Egyptian and Muslim ceramics found in Hanoi».

- ↑ Hoàng Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Relations; 1637 - 1700. Brill Co. ISBN 978-9004156012.

- ↑ «Urbanization: expanding opportunities, but deeper divides | UN DESA | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs». www.un.org. Վերցված է 2023-06-28-ին.

- ↑ «City Life in the Late 19th Century | Rise of Industrial America, 1876-1900 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2023-06-28-ին.

- ↑ Lockard, Craig A. (1994). «Meeting Yesterday Head-on: The Vietnam War in Vietnamese, American, and World History». Journal of World History. 5 (2): 227–270. ISSN 1045-6007. JSTOR 20078600.

- ↑ «About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam - The Economy - Historical Background». Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ 15,0 15,1 «About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ «Overview: Development news, research, data». April 14, 2023. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից June 28, 2023-ին. Վերցված է June 28, 2023-ին.

- ↑ «The World Economy at the Start of the 21st Century, Remarks by Anne O. Krueger, First Deputy Managing Director, IMF». IMF (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2023-06-28-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam - The Economy». Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ Council Of Ministers (March 1989). «Vietnam's New Fertility Policy». Population and Development Review. 15 (1): 169–172. doi:10.2307/1973424. JSTOR 1973424.

- ↑ «About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ «WTO | Accessions: Viet Nam». www.wto.org. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ «About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ Baccini, Leonardo; Impullitti, Giammario; Malesky, Edmund J. (2019). «Globalization and state capitalism: Assessing Vietnam's accession to the WTO» (PDF). Journal of International Economics. 119: 75–92. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2019.02.004. S2CID 158525166.

- ↑ Vuong, Quan-Hoang, Financial Markets in Vietnam's Transition Economy: Facts, Insights, Implications. 978-3-639-23383-4

- ↑ «Recovery from the Asian Crisis and the Role of the IMF -- An IMF Issues Brief». www.imf.org. Վերցված է 2023-07-14-ին.

- ↑ «Economic Growth of Viet Nam». Nerd Economics (անգլերեն). 2020-07-18. Վերցված է 2023-06-28-ին.

- ↑ «House Report 107-198 - APPROVAL OF THE EXTENSION OF NONDISCRIMINATORY TREATMENT WITH RESPECT TO THE PRODUCTS OF THE SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM». www.govinfo.gov. Վերցված է 2023-06-28-ին.

- ↑ 29,00 29,01 29,02 29,03 29,04 29,05 29,06 29,07 29,08 29,09 29,10 29,11 29,12 29,13 29,14 29,15 29,16 29,17 29,18 29,19 29,20 «About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress». Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ Virmani, Arvind (July 2012). «Accelerating And Sustaining Growth: Economic and Political Lessons; by Arvind Virmani; IMF Working Paper 12/185» (PDF). Արխիվացված (PDF) օրիգինալից June 28, 2023-ին. Վերցված է June 28, 2023-ին.

- ↑ Vuong, Quan Hoang; Tran, Tri Dung (2009-06-15). «Financial Turbulences in Vietnam's Emerging Economy: Transformation over 1991-2008 Period» (անգլերեն). Rochester, NY. SSRN 1486204.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(օգնություն) - ↑ «WTO | Accessions: Viet Nam». www.wto.org. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ «WTO | The WTO in brief». www.wto.org. Վերցված է 2023-06-28-ին.

- ↑ «Global Trade Liberalization and the Developing Countries -- An IMF Issues Brief». www.imf.org. Վերցված է 2023-06-28-ին.

- ↑ vietnam will struggle to meet 2012 growth target southeast asia, Bloomberg. Retrieved November 4, 2012

- ↑ Vuong, Quan-Hoang (2014-05-16). «Vietnam's political economy: a discussion on the 1986-2016 period». Working Papers CEB (անգլերեն).

- ↑ 37,0 37,1 VnExpress. «Report paints brighter picture of corruption control in Vietnam - VnExpress International». VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2018-04-25-ին.

- ↑ 38,0 38,1 38,2 38,3 VnExpress. «Report paints brighter picture of corruption control in Vietnam - VnExpress International». VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2018-04-08-ին.

- ↑ Jennings, Ralph. «Vietnam's Corruption Crackdown Is All About Protecting Its Economic Miracle From Its SOEs». Forbes (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2018-04-08-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam's economy expands 7.38%, best rate in a decade, Government & …». archive.is. 2018-09-23. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2018-09-23-ին. Վերցված է 2018-09-23-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam, Asia's newest 'tiger' economy, roars in 2018: QNB». archive.is. 2018-09-23. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2018-09-23-ին. Վերցված է 2018-09-23-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam's Economy Could Soon Be Bigger Than Singapore's». Bloomberg. 28 May 2019. Վերցված է 28 May 2019-ին.

- ↑ Lee, Yen Nee (2021-01-28). «This is Asia's top-performing economy in the Covid pandemic — it's not China». CNBC (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2022-01-21-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam is emerging as a winner from the era of deglobalisation». The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Վերցված է 2022-10-04-ին.

- ↑ VIR, Vietnam Investment Review- (August 26, 2016). «Room remains for growth in luxury hotel segment». Vietnam Investment Review - VIR. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից December 20, 2019-ին. Վերցված է December 20, 2019-ին.

- ↑ «World Economic Outlook Database, April 2022». International Monetary Fund (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2022-08-31-ին.

- ↑ Rosen, Elisabeth (24 April 2014). «Why Can't Vietnam Grow Better Rice?». thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Վերցված է 26 April 2014-ին.

- ↑ «World's Top Exports - Coffee Exports by Country». World's Top Exports. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ 49,0 49,1 49,2 «FAOSTAT». www.fao.org. Վերցված է 2022-11-20-ին.

- ↑ USGS Antimony Production Statistics

- ↑ USGS Tin Production Statistics

- ↑ USGS Bauxite Production Statistics

- ↑ USGS Titanium Production Statistics

- ↑ USGS Manganese Production Statistics

- ↑ USGS Phosphate Production Statistics

- ↑ «What did Viet Nam export in 1996? - The Atlas Of Economic Complexity». Վերցված է 23 July 2016-ին.

- ↑ «Sẽ khởi công xây dựng nhà máy lọc dầu Nghi Sơn vào tháng 5/2013». 17 November 2012. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 13 April 2014-ին. Վերցված է 23 July 2016-ին.

- ↑ 58,0 58,1 Do, Thang Nam; Burke, Paul J.; Nguyen, Hoang Nam; Overland, Indra; Suryadi, Beni; Swandaru, Akbar; Yurnaidi, Zulfikar (2021-12-01). «Vietnam's solar and wind power success: Policy implications for the other ASEAN countries». Energy for Sustainable Development. 65: 1–11. Bibcode:2021ESusD..65....1D. doi:10.1016/j.esd.2021.09.002. hdl:1885/248804. ISSN 0973-0826.

- ↑ «Why Samsung of South Korea is the biggest firm in Vietnam, Why Samsung of South Korea is the biggest firm in Vietnam». The Economist. 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Nagy, Anton D. (30 October 2019). «More Samsung and LG phones will be made in China in 2020».

- ↑ «Samsung Electronics ends mobile phone production in China». Reuters. 2 October 2019. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 2 October 2019-ին. Վերցված է 2 October 2019-ին.

- ↑ «Samsung closes its last Chinese manufacturing plant as sales plummet». www.techspot.com. 6 October 2019.

- ↑ «Samsung is done building smartphones in China». Engadget. 2 October 2019. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 11 November 2020-ին. Վերցված է 20 December 2019-ին.

- ↑ «Samsung admits defeat in China's vast smartphone market». CNN. 4 October 2019.

- ↑ «LG Electronics to shut South Korea phone plant, move production to Vietnam». Reuters. 25 April 2019 – via mobile.reuters.com.

- ↑ TITC. «Hơn 10 triệu lượt khách quốc tế đến Việt Nam trong năm 2016». Tổng cục Du lịch Việt Nam. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից September 26, 2022-ին. Վերցված է 2017-01-02-ին.

- ↑ «UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, December 2020 | World Tourism Organization». UNWTO World Tourism Barometer (English Version). 18 (7): 1–36. 18 December 2020. doi:10.18111/wtobarometereng.2020.18.1.7. S2CID 241989515.

- ↑ «Over 100 arrive in Vietnam on first commercial flight in six months - VnExpress International».

- ↑ «Vietnam proposes tourism travel bubbles within ASEAN - VnExpress International».

- ↑ «Vietnamese tourism adopts cut-price rates and possible 'travel bubble'». 19 May 2020.

- ↑ «Covid-19 resurgence exacts tourism toll - VnExpress International».

- ↑ «Vietnam's target of sending 90,000 workers abroad in 2022 within reach». Վերցված է 2022-06-26-ին.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(օգնություն) - ↑ Vuong Quan Hoang (2003). «Essays on Vietnam's Financial Reforms: Foreign Exchange Statistics and Evidence of Long-Run Equilibrium» (PDF). Economic Studies Review. 43 (6–8). doi:10.2139/ssrn.445080. S2CID 153742102.

- ↑ Riedel, James; Turley, William S. (1999-09-01). «The Politics and Economics of Transition to an Open Market Economy in Viet Nam» (PDF). OECD Development Centre. OECD Development Centre Working Papers (անգլերեն). Paris. 154. doi:10.1787/634117557525. eISSN 1815-1949.

- ↑ Anh, Nguyen Thi Tue; Duc, Luu Minh; Chieu, Trinh Duc (2015-08-18). «The Evolution of Vietnamese Industry» (PDF). Learning to Compete. WIDER Working Paper. 15. doi:10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2014/797-4. ISBN 978-92-9230-797-4. ISSN 1798-7237.

- ↑ Napier, Nancy K.; and Vuong, Quan-Hoang. What we see, why we worry, why we hope: Vietnam going forward. Boise, ID, USA: Boise State University CCI Press, October 2013. 978-0985530587.

- ↑ 77,0 77,1 77,2 «Vietnam's economy expands 6.5 percent in first half».

- ↑ «BBC Vietnamese - Kinh tế - Việt Nam: lạm phát 2011 ở mức 18,6%». 23 December 2011. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «Lạm phát cả năm 2012 khoảng 7,5%». VnExpress. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2013-02-02-ին. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam's top 10 economic events of 2013». 6 May 2014. Վերցված է 19 December 2015-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam's inflation rate to hit over 4 percent in 2014». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 22 December 2015-ին. Վերցված է 19 December 2015-ին.

- ↑ «Barriers to mergers and acquisitions business in Vietnam». 108x. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2011-06-15-ին. Վերցված է 2011-08-12-ին.

- ↑ «M&A Experte Vietnam» (անգլերեն). Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2016-11-10-ին. Վերցված է 2016-11-10-ին.

- ↑ «VTV4 Business TV about M&A in Vietnam and Interview with Christopher Kummmer» (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2016-11-10-ին.

- ↑ «M&A Statistics Vietnam». Վերցված է 7 November 2016-ին.

- ↑ «M&A Statistics by Countries - IMAA-Institute». IMAA-Institute (ամերիկյան անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2018-02-23-ին.

- ↑ «The ASEAN Economic Community's Progress». - InvestAsian. 15 January 2015. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam Reportedly Seeking Military Aid From Both Moscow and Washington». VOA (անգլերեն). 2023-09-25. Վերցված է 2023-09-29-ին.

- ↑ «Opinion: How will Vietnam's upgraded US partnership impact its ties with China, Russia?». South China Morning Post (անգլերեն). 2023-09-17. Վերցված է 2023-09-29-ին.

- ↑ Bank, Asian Development (2007-09-01). ASEAN+3 or ASEAN+6: Which Way Forward? (անգլերեն). Asian Development Bank.

- ↑ 91,0 91,1 91,2 «Vietnam sees 2012 trade surplus as economy slows». Daily Times. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 16 April 2013-ին. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «SƠ BỘ TÌNH HÌNH XUẤT KHẨU, NHẬP KHẨU HÀNG HOÁ CỦA VIỆT NAM THÁNG 12 VÀ 12 THÁNG NĂM 2014 - ThongKeHaiQuan: Hải Quan Việt Nam». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 4 March 2016-ին. Վերցված է 23 July 2016-ին.

- ↑ «TÌNH HÌNH XUẤT KHẨU, NHẬP KHẨU HÀNG HÓA CỦA VIỆT NAM THÁNG 12 VÀ 12 THÁNG NĂM 2011 - TinHoatDong : Hải Quan Việt Nam». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2 April 2015-ին. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ vneconomy (17 January 2013). «Chốt con số xuất siêu 780 triệu USD năm 2012». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2013-02-22-ին.

- ↑ «Tình hình xuất khẩu, nhập khẩu hàng hóa của Việt Nam tháng 12 và năm 2015 - ThongKeHaiQuan: Hải Quan Việt Nam». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 10 June 2016-ին. Վերցված է 23 July 2016-ին.

- ↑ «Số liệu chính thức: Năm 2017 xuất khẩu 214 tỷ USD, xuất siêu 2,92 tỷ USD». baodautu.vn. 16 January 2018.

- ↑ «Preliminary assessment of Vietnam international merchandise trade performance in whole year 2018 : EnglishNews : Vietnam Customs». www.customs.gov.vn. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2020-11-24-ին. Վերցված է 2019-12-20-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam 2019 trade surplus $11.12 billion, beating $9.94 billion forecast: customs». Վերցված է 6 June 2020-ին.

- ↑ «Preliminary assessment of Vietnam international merchandise trade performance in whole year 2020». General Department of Vietnam Customs. Վերցված է 2 April 2021-ին.(չաշխատող հղում)

- ↑ 100,0 100,1 «Tạp chí Cộng Sản - Xuất, nhập khẩu của Việt Nam năm 2012 - kết quả và những vấn đề đặt ra». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 6 November 2014-ին. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam- Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita 2020 - Statistic». Statista. Վերցված է 5 May 2017-ին.

- ↑ Malesky, Edmund J.; Gueorguiev, Dimitar D.; Jensen, Nathan M. (2015). «Monopoly Money: Foreign Investment and Bribery in Vietnam, a Survey Experiment». American Journal of Political Science. 59 (2): 419–439. doi:10.1111/ajps.12126. ISSN 0092-5853. JSTOR 24363575.

- ↑ atinder. «Welcome To The World Of Smokeless Cigarettes!». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 27 May 2013-ին. Վերցված է 23 July 2016-ին.

- ↑ «ASEAN, Australia and New Zealand Leaders' Statement: Entry into Force of the Agreement Establishing the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Area 25 October 2009, Cha am Hua Hin, Thailand» (PDF). Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից (PDF) 29 September 2015-ին. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «ASEAN - Australia - New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA) - ASEAN - Australia - New Zealand Free Trade Agreement». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 16 October 2015-ին. Վերցված է 3 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ 106,0 106,1 106,2 Pushpanathan, Sundram (22 December 2009). «ASEAN Charter: One year and going strong». The Jakarta Post. Վերցված է 1 January 2010-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam: New Trade Agreement with Eurasia Economic Union - Global Legal Monitor». www.LOC.gov. 16 June 2015. Վերցված է 5 May 2017-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam - Chile - WTO and International trade Policies». WTOCenter.vn. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2017-05-13-ին. Վերցված է 5 May 2017-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam - Korea - WTO and International trade Policies». WTOCenter.vn. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2017-05-20-ին. Վերցված է 5 May 2017-ին.

- ↑ «Vietnam - Japan - WTO and International trade Policies». WTOCenter.vn. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2017-05-13-ին. Վերցված է 5 May 2017-ին.

- ↑ «UK strikes Singapore and Vietnam trade deals, start of new era of trade with Asia '». Gov.UK. 10 December 2020. Վերցված է 4 July 2023-ին.

- ↑ «Chuyên trang Thống kê Hải quan :: Hải quan Việt Nam». www.customs.gov.vn. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2019-07-01-ին. Վերցված է 2019-07-01-ին.

- ↑ 113,0 113,1 Le, Van Anh (2023-10-23). «Soviet Legacy of Vietnam's Intellectual Property Law: Big Brother is (No Longer) Watching You». Asian Journal of Comparative Law (անգլերեն). 19: 39–66. doi:10.1017/asjcl.2023.31. ISSN 2194-6078.

- ↑ «The Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018». World Economic Forum.

- ↑ World Bank Group (2018). Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs (PDF) (Report).

- ↑ «The Inclusive Development Index 2018». World Economic Forum.

- ↑ «Sustainable Development Goals». 10 July 2018.

- ↑ «IT Industry Competitiveness Index 2011». globalindex11.bsa.org.

- ↑ «The Global Competitiveness Report 2019» (PDF). Africa Competitiveness 2013. Վերցված է 4 March 2020-ին.

- ↑ «Country Rankings». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 17 November 2010-ին. Վերցված է 4 March 2020-ին.

Գրականություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- Jandl, Thomas (2013). Vietnam in the Global Economy. Lexington Books.

Արտաքին հղումներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

| Վիքիպահեստ նախագծում կարող եք այս նյութի վերաբերյալ հավելյալ պատկերազարդում գտնել Argam Forbes/Ավազարկղ E կատեգորիայում։ |

- Վիետնամի տնտեսություն

- Վիետնամի բիզնես փաստեր

- Արժեթղթերի ազգային կենտրոն

- Արժեթղթեր

- Վիետնամի արտահանման, ներմուծման և առևտրի հաշվեկշիռ Համաշխարհային բանկ

- Վիետնամ «Doi moi»-ն և համաշխարհային ճգնաժամը Արխիվացված 2021-01-24 Wayback Machine-ում (հոդված)

- Միաձուլումներ և ձեռքբերումներ Վիետնամի զարգացող շուկայական տնտեսության մեջ. 1990-2009 թթ.

- Վիետնամի կողմից կիրառվող սակագները, որոնք նախատեսված են ITC-ի ITC շուկա մուտք գործելու քարտեզով, մաքսային սակագների և շուկայի պահանջների առցանց տվյալների բազա