Մասնակից:Rips0/Ավազարկղ

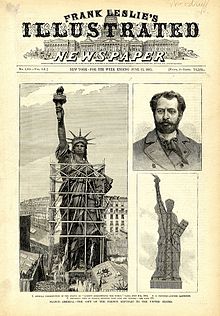

Ազատության արձան, ( անգլ.՝ Statue of Liberty, լրիվ անունն է՝ Ազատությունը, որ լուսավորում է աշխարհը, անգլ.՝ Liberty Enlightening the World, ֆր.՝ La Liberté éclairant le monde), Նյու Յորքի Նյու Յորք նավահանգստի Ազատության կղզու վրա գտնվող նեոդասական ոճով կառուցված վիթխարի արձան է: Պղնձաձույլ արձանը, որը նվեր էր Ֆրանսիայի ժողովրդի կողմից ԱՄՆ ժողովրդին, նախագծվել է ֆրանսիացի քանդակագործ Ֆրեդերիկ Օգյուստ Բարտոլդի կողմից, իսկ մետաղական հիմքը կառուցվել է Գուստավ էյֆելի կողմից: Այն հանձնվել է որպես նվեր ԱՄՆ-ին 1886 թվականի հոկտեմբերի 28-ին:

Ազատության արձանը քանդակված է Լիբերտասի՝ հռոմեական դիցաբանության ազատության աստվածուհու տեսքով, ով իր գլխավերևում՝ աջ ձեռքում, պահում է ջահը, իսկ կնոջ ձախ ձեռքում տաբուլա անսատան է՝ սալիկ, որի վրա հռոմեական թվերով՝ "JULY IV MDCCLXXVI", փորագրված է ԱՄՆ անկախության հռչակագրի ընդունման ամսաթիվը՝ 1776 թվականի հուլիսի 4: Այս արձանը դարձել է ազատության և ԱՄՆ խորհրդանիշը, ինչպես նաև զբոսաշրջային հայտնի կենտրոններից մեկը: Այն արտերկրից ժամանող զբոսաշրջիկների համար կարծես դիմավորող հյուրընկալ լինի:

Բարտոլդին ոգևշնչվել էր ֆրանսիացի իրավունքի պրոֆեսոր և քաղաքագետ Էդուարդ Ռենե դը Լաբուլեից, ով 1865 թվականին հայտարարել էր, որ ցանկացած հուշարձան, որը կկանգնեցվի ԱՄՆ անկախության ձեռք բերման պատվին, պետք է լինի ֆրանսիացի և ամերիկացի ժողովուրդների համատեղ նախագծի արդյունք: Ֆրանսիայում տիրող հետպատերազմյան անկայունության արդյունքում արձանի վրա տարվող աշխատանքները սկսվեցին միայն 1870-ական թվականների սկզբներին: 1875 թվականին Լաբուլեն առաջարկեց, որ Ֆրանսիան ֆինանսավորի արձանի կառուցումը, իսկ ԱՄՆ-ն պետք է որոշեր արձանի կանգնեցման վայրը և կառուցեր պատվանդանը: Մինչ արձանի վերջնական նախագծի հաստատումը Բարտոլդին արդեն ավարտին էր հասցրել գլխի և ջահակիր ձեռքի վրա տարվող աշխատանքները, և այդ հատվածները հրապարակայնորեն ցուցադրվել էին միջազգային ցուցահանդեսներում:

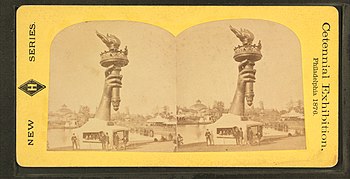

Ջահակիր ձեռքը ցուցադրվել է 1876 թվականին Ֆիլադեֆիայում անցկացված 100 ամյակի ցուցահանդեսի ժամանակ, ինչպես նաև 1876-1882 թվականներին Մանհեթենի Մեդիսոն Սքուեր այգում: Արձանի կառուցման աշխատանքների իրականացման համար իրականացվող դրամական միջոցների հայթհայթման գործընթացը, հատկապես ամերիկացիների մոտ, դանդաղ էր ընթանում: Մինչ 1885 թվականը դրամական միջոցների սղության պատճառով վտանգված էին նաև պատվանդանի կառուցման աշխատանքները: Նյու Յորք Ուորլդի հրատարակիչ Ջոզեֆ Պուլիցերը դրամահավաքի արշավ սկսեց անհրաժեշտ միջոցները ձեռք բերելու նպատակով, և կարողացավ այդ արշավի մեջ ներգրավել մոտ 120000 ներդրողի, որոնցից շատերը մեկ դոլարից էլ պակաս նվիրատվություն արեցին: Արձանը կառուցվել է Ֆրանսիայում, փայտե արկղներով ուղարկվեց, և մոնտաժվեց ու տեղադրվեց արդեն իսկ պատրաստ պատվանդանի վրա այն վայրում, որն այն ժամանակ կոչվում էր Բեդլոեի կղզի: Արձանի կառուցման աշխատանքների ավարտը նշանավորվեց Նյու Յորքի առաջին ժապավենների շքերթով (ticker-tape parade) և արձանին նվիրված արարողությամբ, որը նախագահում էր ԱՄՆ նախագահ Գրովեր Կլիվլենդը:

Արձանը գտնվում էր ԱՄՆ փարոսի Խորհրդի վերահսկողության տակ մինչ 1901 թվականը, դրանից հետո՝ մինչ 1933 թվականը ԱՄՆ Ռազմական նախարարության վերահսկողության տակ, իսկ 1933 թվականից սկսած՝ ԱՄՆ ազգային այգիների ծառայության վերահսկողության տակ: Ջահի մոտ գտնվող պատշգամբի մուտքը այցելուների համար անվտանգության նկատառումներով փակ էր մինչև 1916 թվականը:

Դիզայն և կառուցման գործընթաց

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Ծագում

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ըստ ԱՄՆ ազգային այգիների ծառայության՝ ֆրանսիացիների կողմից Ամերիկայի բնակիչներին արձան նվիրելու առաջարկը առաջին անգամ հնչեցրել է Էդուարդ Ռենե դը Լաբուլեն, ով Ֆրանսիական ստրկության դեմ հասարակության նախագահն էր , ինչպես նաև իր ժամանակների նշանակալի քաղաքական մտածողություն ունեցող անձանցից մեկը: Նախագծի շուրջ խոսակցություններ են սկսվել 1865 թվականի կեսերին աբոլուցիոնիստ Լաբուլեի և քանդակագործ Ֆրեդերիկ Բարտոլդի միջև: Վերսալին մոտ գտնվող իր տանը ընթրիքից հետո տեղի ունեցած խոսակցության ժամանակ Լաբուլեն, ով Ամերկայի քաղաքացիական պատերազմում Միության ջերմեռանդ աջակիցներից էր, ասել է. «Եթե Միացյալ Նահանգներում իրենց անկախությունը խորհրդանշող արձան պետք է կանգնեցվի, ես կարծում եմ, որ տեղին կլինի, որ այն կառուցվի միասնական ջանքերով՝ երկու ժողովուրդների համատեղ աշխատանքի արդյունքում»[1]: 2000 թվականի զեկույցում ԱՄՆ ազգային այգիների ծառայությունը, այնուամենայնիվ, սա համարում է 1885 թվականի գումարի հավաքագրման գրքույկում արձանագրված լեգենդ, իսկ արձանի գաղափարը, ամենայն հավանականությամբ, առաջ է քաշվել 1870 թվականին[2]: Իրենց կայքէջում տեղադրված մեկ այլ էսսեի համաձայն՝ ԱՄՆ ազգային այգիների ծառայությունը պնդում է, որ Լաբուլեն ցանկանում էր խորհրդանշել Միության հաղթանակն ու այդ հաղթանակի հետևանքները. «1865 թվականին ստրկության արգելմամբ և քաղաքացիական պատերազմում տարած հաղթանակով Լաբուլեի ազատության և ժողովրդավարության երազանքները իրականություն էին դառնում Միացյալ Նահանգներում: Այս ձեռքբերումները խորհրդանշելու համար Լաբուլեն առաջարկեց Ֆրանսիայի անունից նվեր կառուցել և նվիրել Միացյալ Նահանգներին: Լաբուլեն հույս ուներ, որ Միացյալ նահանգների վերջին ջեռքբերումների վրա ուշադրություն հրավիրելով ֆրանսիացիները կոգևորվեն և ճնշող միապետությունից իրենց սեփական ժողովրդավարությունը կպահանջեն»[3]:

Ըստ քանդակագործ Ֆրեդերիկ Բարտոլդի, ով հետագայում վերաշարադրեց այս պատմությունը, Լաբուլեի այդ հայտարարությունը ի սկզբանե որպես առաջարկ չի ներկայացվել, սակայն դա ոգեշնչել է Բարտոլդիին[1]: Իմանալով Նապոլեոնի III-ի վարչակարգի կողմից վարվող ճնշումների քաղաքականության մասին, Բարտոլդին անմիջապես այդ նախագիծը կյանքի կոչել չսկսեց, այլ քննարկումներ ունեցավ Լաբուլեի հետ: Բարտոլդին այդ ժամանակ զբաղված էր իր մյուս հնարավոր նախագծերով. 1860-ականների վերջին նա Եգիպտոսի խեդիվ Իսմայիլ փաշային առաջարկեց «Զարգացում» կամ «Եգիպտոսը լույս է մատակարարում Ասիային» նախագիծը[4]: Դա մի հսկայական փարոս էր, որն ունենալու էր հին եգիպտացի հողագործ կնոջ կամ գեղջկուհու տեսք, ով ձեռքում ջահ էր պահելու: Այն տեղադրվելու էր Սուեզի ջրանցքի հյուսիսայի մուտքի մոտ՝ Պորտ Սաիդում: Այս նախագիծը թեպետ ունեցել է էսքիզներ և մոդելներ, սակայն այդպես էլ կյանքի չի կոչվել: Սուեզի համար կար դասական նախատիպ՝ Հռոդոսի կոթողը: Այն Հունաստանի արևի աստծուն՝ Հելիոսին, նվիրված հին բրոնզաձույլ արձան էր: Ենթադրվում է, որ այդ արձանը ունեցել է 100 ոտնաչափ (30 մետր) բարձրություն և տեղակայված է եղել նավահանգստի մուտքի մոտ՝ լուսավորելով նավերի ճանապարհը[5]: Ե՛վ խեդիվը, և Լեսեպսները մերժել են Բարտոլդիի առաջարկը՝ դա հիմնավորելով նախագծի ծախսատարությամբ[6]: Իսկ Պորտ Սաիդի փարոսը կառուցեց Ֆրանսուա Կոյնեն 1869 թվականին:

Մեկ այլ մեծ նախագիծ չեղարկվեց ֆրասն-պրուսական պատերազմի պատճառով, որտեղ Բարտոլդին ծառայում էր որպես ոստիկանության մայոր: Պատերազմում Նապոլեոնի III-ը գերի ընկավ և գահընկեց արվեց: Բարտոլդիի հայրական նահանգ Էլզասը անցավ Պրուսիային, իսկ Ֆրանսիայում հաստատվեց լիբերալ հանրապետություն[1]: Քանի որ Բարտոլդին մտադրված էր այցելել Միացյալ Նահանգներ, նա և Լաբուլեն որոշեցին, որ իրենց գաղափարը ազդեցիկ ամերիկացիների հետ քննարկելու ճիշտ ժամանակն է[7]: 1871 թվականի հունիսին Բարտոլդին անցավ Ատլանտյան օվկիանոսը՝ ձեռքում ունենալով Լաբուլեի կողմից ստորագրված նամակները նախագծի մասին[8]:

Ժամանելով Նյու Յորքի նավահանգիստ՝ Բարտոլդին որպես արձանի տեղակայման վայր իր համար առանձնացրեց Բեդլոուի կղզին (ներկայումս՝ Ազատության կղզին): Ընտրությունը պայմանավորվախ էր նրանով, որ Նյու Յորք ժամանող նավերը նավարկում էին նրա մոտով: Նա ոգևորվեց, երբ իմացավ, որ կղզին պատկանում է ԱՄՆ կառավարությանը. այն 1800 թվականին տրամադրվել էր Նյու Յորքի օրենսդիր մարմնին նավահանգստի պաշտպանությունն իրականացնելու նպատակով: Լաբուլեին գրած իր նամակում նա նշում է, որ գտել է ցամաք, որը բոլոր նահանգներինն է[9]: Մի շարք ազդեցիկ նյույորքցիների հանդիպելուց զատ Բարտոլդին հանդիպեց նաև նախագահ Ուլիսես Ս. գրանտի հետ, ով հավաստիացրեց, որ արձանը տեղակայելու թույլտվությունը ձեռք բերելը այդքան էլ բարդ չի լինի[10]: Բարտոլդին երկու անգամ երկաթուղով շրջագայել է ԱՄՆ-ում և հանդիպել մի շարք ամերիկացիների, ովքեր, իր կարծիքով, կարող են աջակցել նախագծին[8]: Բայց նրան մտահոգում էր այն, որ Ատլանտյան օվկիանոսի երկու կողմերում էլ հասարակական կարծիքը նախագծի վերաբերյալ բավականաչափ աջակցություն չի ցուցաբերում, և ինքն ու Լաբուլեն որոշեցին մի փոքր հետաձգել հանրային արշավի մեկնարկը[11]:

Բարտոլդին իր այս գաղափարի առաջին մոդելը նախագծել է 1870 թվականին[12]: Բարտոլդի ընկերներից մեկի որդին՝ ԱՄՆ արտիստ Ջոն ԼըՖարժը, ավելի ուշ պնդում էր, որ առաջին էսքիզները Բարտոլդը արել է ԱՄՆ կատարած այցի ընթացքում ԼըՖարժի Ռոդ Այլենդ ստուդիայում: Վերադառնալով Ֆրանսիա Բարտոլդը շարունակում էր զարգացնել իր գաղափարը[12]: Նա նաև աշխատում էր մի շարք այլ քանդակների կերտման ուղղությամբ, որոնք նպատակ ունեին Պրուսիայի կողմից կրած պարտությունից հետո խրախուսել հայրենասիրությունը Ֆրանսիայում: Այդ քանդակներից մեկը Բելֆորի առյուծն էր:Դա արձան է Բելֆորի ամրոցի մոտակայքում, որը դիմադրեց պրուսական արշավանքներին մոտ երեք ամիս: Հանդուգն առյուծը, որն ունի 73 ոտնաչափ (22 մետր) երկարություն և դրա կիսով չափ բարձրություն, ռոմանտիզմի բնորոշ զգացմունքային որակներ ունի, որոնք դրսևորվում են հետագայում նաև Ազատության արձանում[13]:

Դիզայն, ոճ, խորհրդանիշներ

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Բարտոլդին և Լաբուլեն քննարկում էին Ամերիկայի անկախության գաղափարը առավել ճիշտ արտահայտելու ձևերը[14]: Ամերիկայի պատմության վաղ շրջանում կանացի երկու կերպարներ էին գերազանցապես օգտագործվում որպես ազգի մշակութային խորհրդանիշներ[15]: Այդ խորհրդանիշներից մեկը Կոլումբիան է, որը դիտվում է որպես Միացյալ Նահանգների մարմնավորում ճիշտ այնպես, ինչպես Բրիտանիան ասոցացվում է Միացյալ Թագավորության և Մարիանը՝ Ֆրանսիայի հետ: Կոլումբիան փոխարինելու եկավ հնդկացի աստվածուհուն, որովհետև վերջինիս առկայությունը անքաղաքակիրթ և վիրավորական էր համարվում ամերիկացիների նկատմամբ[15]: Ամերիկյան մշակույթի մյուս հռչակավոր կերպարը ազատության ներկայացուցիչն էր ( Liberty), որը ծագել էր Լիբերտասից՝ ազատության աստվածուհի, ում երկրպագում էին Հին Հռոմում, հատկապես ազատություն ստացած ստրուկների շրջանում: Ազատության խորհրդանիշը հայտնվում էր այն ժամանակվա ամերիկյան մետաղադրամների վրա[14], ինչպես նաև ժողովրդական և քաղաքացիական արվեստում՝ ներառելով Թոմաս Քրաֆորդի Ազատության արձանը (1863) Կապիտոլիումի գմբեթին[14]:

18 և 19-րդ դարերի արտիստները ձգտում էին հանրապետական գաղափարներ տարածել հիմնականում օգտագործելով Լիբերտասի կերպարը որպես այլաբանական խորհրդանիշ[14]: Ազատության կերպարը պատկերված էր նաև Ֆրանսիայի Մեծ կնիքի վրա[14]: Այնուամենայնիվ, Բարտոլդին և Լաբուլեն խուսափում էին հեղափոխական ազատության պատկերից, որը առկա է Էժեն Դելակրուայի հայտնի «Ժողովրդին առաջնորդող ազատությունը» կտավում (1830 թվական): Այս նկարում, որը խորհրդանշում է Ֆրանսիայի հուլիսյան հեղափոխությունը, կիսամերկ կինը՝ Լիբըրթին, առաջնորդում է զորքին մահացածների դիակների վրայով[15]: Լաբուլեն հեղափոխության ջատագով չէր, և Բարտոլդի ստեղծած կերպարը պետք է ամբողջությամբ հագնված լիներ[15]: Դելակրուայի նկարում պատկերված բռնության տեսարանի փոխարեն Բարտոլդը ցանկանում էր իր արձանին խաղաղ տեսք տալ և որոշեց, որ իր արձանի ձեռքում պետք է լինի առաջընթաց խորհրդանշող ջահը[16]:

Թոմաս Քրաֆորդի Ազատության արձանը նախագծվել է 1850-ական թվականների սկզբին:

Crawford's statue was designed in the early 1850s. It was originally to be crowned with a pileus, the cap given to emancipated slaves in ancient Rome. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a Southerner who would later serve as President of the Confederate States of America, was concerned that the pileus would be taken as an abolitionist symbol. He ordered that it be changed to a helmet.[17]

Delacroix's figure wears a pileus,[15] and Bartholdi at first considered placing one on his figure as well. Instead, he used a diadem, or crown, to top its head.[18] In so doing, he avoided a reference to Marianne, who invariably wears a pileus.[19] The seven rays form a halo or aureole.[20] They evoke the sun, the seven seas, and the seven continents,[21] and represent another means, besides the torch, whereby Liberty enlightens the world.[16]

Bartholdi's early models were all similar in concept: a female figure in neoclassical style representing liberty, wearing a stola and pella (gown and cloak, common in depictions of Roman goddesses) and holding a torch aloft. According to popular accounts, the face was modeled after that of Charlotte Beysser Bartholdi, the sculptor's mother,[22] but Regis Huber, the curator of the Bartholdi Museum is on record as saying that this, as well as other similar speculations, have no basis in fact.[23] He designed the figure with a strong, uncomplicated silhouette, which would be set off well by its dramatic harbor placement and allow passengers on vessels entering New York Bay to experience a changing perspective on the statue as they proceeded toward Manhattan. He gave it bold classical contours and applied simplified modeling, reflecting the huge scale of the project and its solemn purpose.[16] Bartholdi wrote of his technique:

| The surfaces should be broad and simple, defined by a bold and clear design, accentuated in the important places. The enlargement of the details or their multiplicity is to be feared. By exaggerating the forms, in order to render them more clearly visible, or by enriching them with details, we would destroy the proportion of the work. Finally, the model, like the design, should have a summarized character, such as one would give to a rapid sketch. Only it is necessary that this character should be the product of volition and study, and that the artist, concentrating his knowledge, should find the form and the line in its greatest simplicity.[24] |

Bartholdi made alterations in the design as the project evolved. Bartholdi considered having Liberty hold a broken chain, but decided this would be too divisive in the days after the Civil War. The erected statue does stride over a broken chain, half-hidden by her robes and difficult to see from the ground.[18] Bartholdi was initially uncertain of what to place in Liberty's left hand; he settled on a tabula ansata,[25] used to evoke the concept of law.[26] Though Bartholdi greatly admired the United States Constitution, he chose to inscribe "JULY IV MDCCLXXVI" on the tablet, thus associating the date of the country's Declaration of Independence with the concept of liberty.[25]

Bartholdi interested his friend and mentor, architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, in the project.[23] As chief engineer,[23] Viollet-le-Duc designed a brick pier within the statue, to which the skin would be anchored.[27] After consultations with the metalwork foundry Gaget, Gauthier & Co., Viollet-le-Duc chose the metal which would be used for the skin, copper sheets, and the method used to shape it, repoussé, in which the sheets were heated and then struck with wooden hammers.[23][28] An advantage of this choice was that the entire statue would be light for its volume, as the copper need be only 0.094 inches (2.4 mm) thick. Bartholdi had decided on a height of just over 151 feet (46 m) for the statue, double that of Italy's Sancarlone and the German statue of Arminius, both made with the same method.[29]

Announcement and early work

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]By 1875, France was enjoying improved political stability and a recovering postwar economy. Growing interest in the upcoming Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia led Laboulaye to decide it was time to seek public support.[30] In September 1875, he announced the project and the formation of the Franco-American Union as its fundraising arm. With the announcement, the statue was given a name, Liberty Enlightening the World.[31] The French would finance the statue; Americans would be expected to pay for the pedestal.[32] The announcement provoked a generally favorable reaction in France, though many Frenchmen resented the United States for not coming to their aid during the war with Prussia.[31] French monarchists opposed the statue, if for no other reason than it was proposed by the liberal Laboulaye, who had recently been elected a senator for life.[32] Laboulaye arranged events designed to appeal to the rich and powerful, including a special performance at the Paris Opera on April 25, 1876, that featured a new cantata by composer Charles Gounod. The piece was titled La Liberté éclairant le monde, the French version of the statue's announced name.[31]

Initially focused on the elites, the Union was successful in raising funds from across French society. Schoolchildren and ordinary citizens gave, as did 181 French municipalities. Laboulaye's political allies supported the call, as did descendants of the French contingent in the American Revolutionary War. Less idealistically, contributions came from those who hoped for American support in the French attempt to build the Panama Canal. The copper may have come from multiple sources and some of it is said to have come from a mine in Visnes, Norway,[33] though this has not been conclusively determined after testing samples.[34] According to Cara Sutherland in her book on the statue for the Museum of the City of New York, 200,000 pounds (91,000 kg) was needed to build the statue, and the French copper industrialist Eugène Secrétan donated 128,000 pounds (58,000 kg) of copper.[35]

Although plans for the statue had not been finalized, Bartholdi moved forward with fabrication of the right arm, bearing the torch, and the head. Work began at the Gaget, Gauthier & Co. workshop.[36] In May 1876, Bartholdi traveled to the United States as a member of a French delegation to the Centennial Exhibition,[37] and arranged for a huge painting of the statue to be shown in New York as part of the Centennial festivities.[38] The arm did not arrive in Philadelphia until August; because of its late arrival, it was not listed in the exhibition catalogue, and while some reports correctly identified the work, others called it the "Colossal Arm" or "Bartholdi Electric Light". The exhibition grounds contained a number of monumental artworks to compete for fairgoers' interest, including an outsized fountain designed by Bartholdi.[39] Nevertheless, the arm proved popular in the exhibition's waning days, and visitors would climb up to the balcony of the torch to view the fairgrounds.[40] After the exhibition closed, the arm was transported to New York, where it remained on display in Madison Square Park for several years before it was returned to France to join the rest of the statue.[40]

During his second trip to the United States, Bartholdi addressed a number of groups about the project, and urged the formation of American committees of the Franco-American Union.[41] Committees to raise money to pay for the foundation and pedestal were formed in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia.[42] The New York group eventually took on most of the responsibility for American fundraising and is often referred to as the "American Committee".[43] One of its members was 19-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, the future governor of New York and president of the United States.[41] On March 3, 1877, on his final full day in office, President Grant signed a joint resolution that authorized the President to accept the statue when it was presented by France and to select a site for it. President Rutherford B. Hayes, who took office the following day, selected the Bedloe's Island site that Bartholdi had proposed.[44]

Construction in France

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

On his return to Paris in 1877, Bartholdi concentrated on completing the head, which was exhibited at the 1878 Paris World's Fair. Fundraising continued, with models of the statue put on sale. Tickets to view the construction activity at the Gaget, Gauthier & Co. workshop were also offered.[45] The French government authorized a lottery; among the prizes were valuable silver plate and a terracotta model of the statue. By the end of 1879, about 250,000 francs had been raised.[46]

The head and arm had been built with assistance from Viollet-le-Duc, who fell ill in 1879. He soon died, leaving no indication of how he intended to transition from the copper skin to his proposed masonry pier.[47] The following year, Bartholdi was able to obtain the services of the innovative designer and builder Gustave Eiffel.[45] Eiffel and his structural engineer, Maurice Koechlin, decided to abandon the pier and instead build an iron truss tower. Eiffel opted not to use a completely rigid structure, which would force stresses to accumulate in the skin and lead eventually to cracking. A secondary skeleton was attached to the center pylon, then, to enable the statue to move slightly in the winds of New York Harbor and as the metal expanded on hot summer days, he loosely connected the support structure to the skin using flat iron bars[23] which culminated in a mesh of metal straps, known as "saddles", that were riveted to the skin, providing firm support. In a labor-intensive process, each saddle had to be crafted individually.[48][49] To prevent galvanic corrosion between the copper skin and the iron support structure, Eiffel insulated the skin with asbestos impregnated with shellac.[50]

Eiffel's design made the statue one of the earliest examples of curtain wall construction, in which the exterior of the structure is not load bearing, but is instead supported by an interior framework. He included two interior spiral staircases, to make it easier for visitors to reach the observation point in the crown.[51] Access to an observation platform surrounding the torch was also provided, but the narrowness of the arm allowed for only a single ladder, 40 feet (12 m) long.[52] As the pylon tower arose, Eiffel and Bartholdi coordinated their work carefully so that completed segments of skin would fit exactly on the support structure.[53] The components of the pylon tower were built in the Eiffel factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret.[54]

The change in structural material from masonry to iron allowed Bartholdi to change his plans for the statue's assembly. He had originally expected to assemble the skin on-site as the masonry pier was built; instead he decided to build the statue in France and have it disassembled and transported to the United States for reassembly in place on Bedloe's Island.[55]

In a symbolic act, the first rivet placed into the skin, fixing a copper plate onto the statue's big toe, was driven by United States Ambassador to France Levi P. Morton.[56] The skin was not, however, crafted in exact sequence from low to high; work proceeded on a number of segments simultaneously in a manner often confusing to visitors.[57] Some work was performed by contractors—one of the fingers was made to Bartholdi's exacting specifications by a coppersmith in the southern French town of Montauban.[58] By 1882, the statue was complete up to the waist, an event Barthodi celebrated by inviting reporters to lunch on a platform built within the statue.[59] Laboulaye died in 1883. He was succeeded as chairman of the French committee by Ferdinand de Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal. The completed statue was formally presented to Ambassador Morton at a ceremony in Paris on July 4, 1884, and de Lesseps announced that the French government had agreed to pay for its transport to New York.[60] The statue remained intact in Paris pending sufficient progress on the pedestal; by January 1885, this had occurred and the statue was disassembled and crated for its ocean voyage.[61]

The committees in the United States faced great difficulties in obtaining funds for the construction of the pedestal. The Panic of 1873 had led to an economic depression that persisted through much of the decade. The Liberty statue project was not the only such undertaking that had difficulty raising money: construction of the obelisk later known as the Washington Monument sometimes stalled for years; it would ultimately take over three-and-a-half decades to complete.[62] There was criticism both of Bartholdi's statue and of the fact that the gift required Americans to foot the bill for the pedestal. In the years following the Civil War, most Americans preferred realistic artworks depicting heroes and events from the nation's history, rather than allegorical works like the Liberty statue.[62] There was also a feeling that Americans should design American public works—the selection of Italian-born Constantino Brumidi to decorate the Capitol had provoked intense criticism, even though he was a naturalized U.S. citizen.[63] Harper's Weekly declared its wish that "M. Bartholdi and our French cousins had 'gone the whole figure' while they were about it, and given us statue and pedestal at once."[64] The New York Times stated that "no true patriot can countenance any such expenditures for bronze females in the present state of our finances."[65] Faced with these criticisms, the American committees took little action for several years.[65]

Design

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The foundation of Bartholdi's statue was to be laid inside Fort Wood, a disused army base on Bedloe's Island constructed between 1807 and 1811. Since 1823, it had rarely been used, though during the Civil War, it had served as a recruiting station.[66] The fortifications of the structure were in the shape of an eleven-point star. The statue's foundation and pedestal were aligned so that it would face southeast, greeting ships entering the harbor from the Atlantic Ocean.[67] In 1881, the New York committee commissioned Richard Morris Hunt to design the pedestal. Within months, Hunt submitted a detailed plan, indicating that he expected construction to take about nine months.[68] He proposed a pedestal 114 feet (35 m) in height; faced with money problems, the committee reduced that to 89 feet (27 m).[69]

Hunt's pedestal design contains elements of classical architecture, including Doric portals, as well as some elements influenced by Aztec architecture.[23] The large mass is fragmented with architectural detail, in order to focus attention on the statue.[69] In form, it is a truncated pyramid, 62 feet (19 m) square at the base and 39.4 feet (12.0 m) at the top. The four sides are identical in appearance. Above the door on each side, there are ten disks upon which Bartholdi proposed to place the coats of arms of the states (between 1876 and 1889, there were 38 U.S. states), although this was not done. Above that, a balcony was placed on each side, framed by pillars. Bartholdi placed an observation platform near the top of the pedestal, above which the statue itself rises.[70] According to author Louis Auchincloss, the pedestal "craggily evokes the power of an ancient Europe over which rises the dominating figure of the Statue of Liberty".[69] The committee hired former army General Charles Pomeroy Stone to oversee the construction work.[71] Construction on the 15-foot-deep (4.6 m) foundation began in 1883, and the pedestal's cornerstone was laid in 1884.[68] In Hunt's original conception, the pedestal was to have been made of solid granite. Financial concerns again forced him to revise his plans; the final design called for poured concrete walls, up to 20 feet (6.1 m) thick, faced with granite blocks.[72][73] This Stony Creek granite came from the Beattie Quarry in Branford, Connecticut.[74] The concrete mass was the largest poured to that time.[73]

Norwegian immigrant civil engineer Joachim Goschen Giæver designed the structural framework for the Statue of Liberty. His work involved design computations, detailed fabrication and construction drawings, and oversight of construction. In completing his engineering for the statue's frame, Giæver worked from drawings and sketches produced by Gustave Eiffel.[75]

Fundraising

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Fundraising for the statue had begun in 1882. The committee organized a large number of money-raising events.[76] As part of one such effort, an auction of art and manuscripts, poet Emma Lazarus was asked to donate an original work. She initially declined, stating she could not write a poem about a statue. At the time, she was also involved in aiding refugees to New York who had fled anti-Semitic pogroms in eastern Europe. These refugees were forced to live in conditions that the wealthy Lazarus had never experienced. She saw a way to express her empathy for these refugees in terms of the statue.[77] The resulting sonnet, "The New Colossus", including the iconic lines "Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free", is uniquely identified with the Statue of Liberty and is inscribed on a plaque in the museum in its base.[78]

Even with these efforts, fundraising lagged. Grover Cleveland, the governor of New York, vetoed a bill to provide $50,000 for the statue project in 1884. An attempt the next year to have Congress provide $100,000, sufficient to complete the project, also failed. The New York committee, with only $3,000 in the bank, suspended work on the pedestal. With the project in jeopardy, groups from other American cities, including Boston and Philadelphia, offered to pay the full cost of erecting the statue in return for relocating it.[79]

Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World, a New York newspaper, announced a drive to raise $100,000—the equivalent of $2.3 million today.[80] Pulitzer pledged to print the name of every contributor, no matter how small the amount given.[81] The drive captured the imagination of New Yorkers, especially when Pulitzer began publishing the notes he received from contributors. "A young girl alone in the world" donated "60 cents, the result of self denial."[82] One donor gave "five cents as a poor office boy's mite toward the Pedestal Fund." A group of children sent a dollar as "the money we saved to go to the circus with."[83] Another dollar was given by a "lonely and very aged woman."[82] Residents of a home for alcoholics in New York's rival city of Brooklyn—the cities would not merge until 1898—donated $15; other drinkers helped out through donation boxes in bars and saloons.[84] A kindergarten class in Davenport, Iowa, mailed the World a gift of $1.35.[82] As the donations flooded in, the committee resumed work on the pedestal.[85]

Construction

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]On June 17, 1885, the French steamer Isère, arrived in New York with the crates holding the disassembled statue on board. New Yorkers displayed their new-found enthusiasm for the statue. Two hundred thousand people lined the docks and hundreds of boats put to sea to welcome the ship.[86][87] After five months of daily calls to donate to the statue fund, on August 11, 1885, the World announced that $102,000 had been raised from 120,000 donors, and that 80 percent of the total had been received in sums of less than one dollar.[88]

Even with the success of the fund drive, the pedestal was not completed until April 1886. Immediately thereafter, reassembly of the statue began. Eiffel's iron framework was anchored to steel I-beams within the concrete pedestal and assembled.[89] Once this was done, the sections of skin were carefully attached.[90] Due to the width of the pedestal, it was not possible to erect scaffolding, and workers dangled from ropes while installing the skin sections. Nevertheless, no one died during the construction.[91] Bartholdi had planned to put floodlights on the torch's balcony to illuminate it; a week before the dedication, the Army Corps of Engineers vetoed the proposal, fearing that ships' pilots passing the statue would be blinded. Instead, Bartholdi cut portholes in the torch—which was covered with gold leaf—and placed the lights inside them.[92] A power plant was installed on the island to light the torch and for other electrical needs.[93] After the skin was completed, renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, co-designer of New York's Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park, supervised a cleanup of Bedloe's Island in anticipation of the dedication.[94]

Dedication

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

A ceremony of dedication was held on the afternoon of October 28, 1886. President Grover Cleveland, the former New York governor, presided over the event.[95] On the morning of the dedication, a parade was held in New York City; estimates of the number of people who watched it ranged from several hundred thousand to a million. President Cleveland headed the procession, then stood in the reviewing stand to see bands and marchers from across America. General Stone was the grand marshal of the parade. The route began at Madison Square, once the venue for the arm, and proceeded to the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan by way of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, with a slight detour so the parade could pass in front of the World building on Park Row. As the parade passed the New York Stock Exchange, traders threw ticker tape from the windows, beginning the New York tradition of the ticker-tape parade.[96]

A nautical parade began at 12:45 p.m., and President Cleveland embarked on a yacht that took him across the harbor to Bedloe's Island for the dedication.[97] De Lesseps made the first speech, on behalf of the French committee, followed by the chairman of the New York committee, Senator William M. Evarts. A French flag draped across the statue's face was to be lowered to unveil the statue at the close of Evarts's speech, but Bartholdi mistook a pause as the conclusion and let the flag fall prematurely. The ensuing cheers put an end to Evarts's address.[96] President Cleveland spoke next, stating that the statue's "stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man's oppression until Liberty enlightens the world".[98] Bartholdi, observed near the dais, was called upon to speak, but he declined. Orator Chauncey M. Depew concluded the speechmaking with a lengthy address.[99]

No members of the general public were permitted on the island during the ceremonies, which were reserved entirely for dignitaries. The only females granted access were Bartholdi's wife and de Lesseps's granddaughter; officials stated that they feared women might be injured in the crush of people. The restriction offended area suffragists, who chartered a boat and got as close as they could to the island. The group's leaders made speeches applauding the embodiment of Liberty as a woman and advocating women's right to vote.[98] A scheduled fireworks display was postponed until November 1 because of poor weather.[100]

Shortly after the dedication, The Cleveland Gazette, an African American newspaper, suggested that the statue's torch not be lit until the United States became a free nation "in reality":

| "Liberty enlightening the world," indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders. Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the "liberty" of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed, perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed. The idea of the "liberty" of this country "enlightening the world," or even Patagonia, is ridiculous in the extreme.[101] |

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 1,2 Harris, 1985, էջեր 7–9

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «NPS African American» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ «Abolition». National Park Service. Վերցված է July 7, 2014-ին.

- ↑ «The Statue of Liberty and its Ties to the Middle East» (PDF). University of Chicago. Վերցված է February 8, 2017-ին.

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 7–8

- ↑ Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. էջ 243. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 60–61

- ↑ 8,0 8,1 Moreno, 2000, էջեր 39–40

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 12–13

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 102–103

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 16–17

- ↑ 12,0 12,1 Khan, 2010, էջ 85

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 10–11

- ↑ 14,0 14,1 14,2 14,3 14,4 Sutherland, 2003, էջեր 17–19

- ↑ 15,0 15,1 15,2 15,3 15,4 Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «dela» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ 16,0 16,1 16,2 Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «Turner 2000» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 96–97

- ↑ 18,0 18,1 Khan, 2010, էջեր 105–108

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «Blume 2004-07-16» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «faq1» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «mint» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջեր 52–53, 55, 87

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 23,2 23,3 23,4 23,5 Interviewed for Watson, Corin. Statue of Liberty: Building a Colossus (TV documentary, 2001)

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «Bartholdi 1885 p42» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ 25,0 25,1 Khan, 2010, էջեր 108–111

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «faq2» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 120

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 118, 125

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 26

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 121

- ↑ 31,0 31,1 31,2 Khan, 2010, էջեր 123–125

- ↑ 32,0 32,1 Harris, 1985, էջեր 44–45

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «News of Norway» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «NYTimes 2009-07-02 part 2» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Sutherland, 2003, էջ 36

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 126–128

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 25

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 26

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 130

- ↑ 40,0 40,1 Harris, 1985, էջ 49

- ↑ 41,0 41,1 Khan, 2010, էջ 134

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 30

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջ 94

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 135

- ↑ 45,0 45,1 Khan, 2010, էջ 137

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 32

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 136–137

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջ 22

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 139–143

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 30

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 33

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 32

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 34

- ↑ «La tour a vu le jour à Levallois». Le Parisien (ֆրանսերեն). April 30, 2004. Վերցված է December 8, 2012-ին.

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 144

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «PBS StLi timeline» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 36–38

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 39

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 38

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 37

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 38

- ↑ 62,0 62,1 Khan, 2010, էջեր 159–160

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 163

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 161

- ↑ 65,0 65,1 Khan, 2010, էջ 160

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջ 91

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «statistics» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ 68,0 68,1 Khan, 2010, էջ 169

- ↑ 69,0 69,1 69,2 Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «stal» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «Bartholdi 1885 p62» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 71–72

- ↑ Sutherland, 2003, էջեր 49–50

- ↑ 73,0 73,1 Moreno, 2000, էջեր 184–186

- ↑ «Branford's History Is Set in Stone». Connecticut Humanities.

- ↑ «STRUCTUREmag – Structural Engineering Magazine, Tradeshow: Joachim Gotsche Giaver». archive.org. November 27, 2012. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից November 27, 2012-ին.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 163–164

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջեր 165–166

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջեր 172–175

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «Levine Story 1961» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «meas» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: - ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջեր 40–41

- ↑ 82,0 82,1 82,2 Harris, 1985, էջ 105

- ↑ Sutherland, 2003, էջ 51

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 107

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 110–111

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 112

- ↑ «The Isere-Bartholdi Gift Reaches the Horsehoe Safely» (PDF). The Evening Post. June 17, 1885. Վերցված է February 11, 2013-ին.

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 114

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջ 19

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 49

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջ 64

- ↑ Hayden, Despont, էջ 36

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջեր 133–134

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջ 65

- ↑ Khan, 2010, էջ 176

- ↑ 96,0 96,1 Khan, 2010, էջեր 177–178

- ↑ Bell, Abrams, էջ 52

- ↑ 98,0 98,1 Harris, 1985, էջ 127

- ↑ Moreno, 2000, էջ 71

- ↑ Harris, 1985, էջ 128

- ↑ Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ Սխալ

<ref>պիտակ՝ «Cleveland Gazette 1886-11-27» անվանումով ref-երը տեքստ չեն պարունակում: