Մասնակից:Asryan2/Ավազարկղ

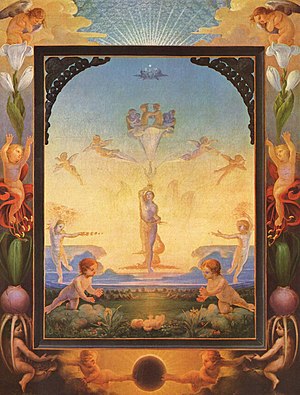

Ռոմանտիզմը (վիպապաշտություն, հայտնի է նաև որպես ռոմանտիզմի դարաշրջան) գեղարվեստական, գրական, երաժշտական և մտավոր շարժում էր, որը սկիզբ էր առել մոտավորապես 18-րդ դարավերջում Եվրոպայում և ծաղկում ապրել մոտ 1800-1850-ականներին։ Ռոմանտիզմին բնորոշ էր շեշտադրումը զգացմունքների և ինդիվիդուալիզմի վրա, ինչպես նաև անցյալի և բնության փառաբանումը՝ գերադասելով միջնադարյանը և ոչ՝ դասականը։ Դա որոշ չափով արձագանք էր արդյունաբերական հեղաշրջմանը, լուսավորության դարաշրջանի արիստոկրատական սոցիալ-քաղաքական նորմերին, ինչպես նաև բնության գիտական ռացիոնալացմանը, այսինքն՝ մոդերնիզմի բոլոր բաղադրիչներին։ Դա առավել ուժգին մարմնավորվել է կերպարվեստում, երաժշտության, գրականության մեջ, սակայն մեծ ազդեցություն է ունեցել նաև պատմագրության, սոցիալական և բնական գիտությունների, կրթության մեջ։ Այն նշանակալի և բազմակողմանի ազդե ցություն է ունեցել քաղաքականության վրա, իսկ ռոմանտիկ մտածողները ազդել են լիբերալիզմի, ռադիկալիզմի, պահպանողականության և ազգայնականության գաղափարների վրա։

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement that originated in Europe toward the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate period from 1800 to 1850. Romanticism was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism as well as glorification of all the past and nature, preferring the medieval rather than the classical. It was partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution,[1] the aristocratic social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment, and the scientific rationalization of nature—all components of modernity.[2] It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography,[3] education,[4] the social sciences, and the natural sciences.[5]Կաղապար:Failed verification It had a significant and complex effect on politics, with romantic thinkers influencing liberalism, radicalism, conservatism and nationalism.[6]

The movement emphasized intense emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as apprehension, horror and terror, and awe—especially that experienced in confronting the new aesthetic categories of the sublimity and beauty of nature. It elevated folk art and ancient custom to something noble, but also spontaneity as a desirable characteristic (as in the musical impromptu). In contrast to the Rationalism and Classicism of the Enlightenment, Romanticism revived medievalism[7] and elements of art and narrative perceived as authentically medieval in an attempt to escape population growth, early urban sprawl, and industrialism.

Although the movement was rooted in the German Sturm und Drang movement, which preferred intuition and emotion to the rationalism of the Enlightenment, the events and ideologies of the French Revolution were also proximate factors. Romanticism assigned a high value to the achievements of "heroic" individualists and artists, whose examples, it maintained, would raise the quality of society. It also promoted the individual imagination as a critical authority allowed of freedom from classical notions of form in art. There was a strong recourse to historical and natural inevitability, a Zeitgeist, in the representation of its ideas. In the second half of the 19th century, Realism was offered as a polar opposite to Romanticism.[8] The decline of Romanticism during this time was associated with multiple processes, including social and political changes and the spread of nationalism.[9]

Defining Romanticism[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Basic characteristics[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The nature of Romanticism may be approached from the primary importance of the free expression of the feelings of the artist. The importance the Romantics placed on emotion is summed up in the remark of the German painter Caspar David Friedrich, "the artist's feeling is his law".[10] To William Wordsworth, poetry should begin as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings", which the poet then "recollect[s] in tranquility", evoking a new but corresponding emotion the poet can then mold into art.[11]

To express these feelings, it was considered the content of art had to come from the imagination of the artist, with as little interference as possible from "artificial" rules dictating what a work should consist of. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and others believed there were natural laws the imagination—at least of a good creative artist—would unconsciously follow through artistic inspiration if left alone.[12] As well as rules, the influence of models from other works was considered to impede the creator's own imagination, so that originality was essential. The concept of the genius, or artist who was able to produce his own original work through this process of creation from nothingness, is key to Romanticism, and to be derivative was the worst sin.[13][14][15] This idea is often called "romantic originality".[16] Translator and prominent Romantic August Wilhelm Schlegel argued in his Lectures on Dramatic Arts and Letters that the most phenomenal power of human nature is its capacity to divide and diverge into opposite directions.[17]

Not essential to Romanticism, but so widespread as to be normative, was a strong belief and interest in the importance of nature. This particularly in the effect of nature upon the artist when he is surrounded by it, preferably alone. In contrast to the usually very social art of the Enlightenment, Romantics were distrustful of the human world, and tended to believe a close connection with nature was mentally and morally healthy. Romantic art addressed its audiences with what was intended to be felt as the personal voice of the artist. So, in literature, "much of romantic poetry invited the reader to identify the protagonists with the poets themselves".[18]

According to Isaiah Berlin, Romanticism embodied "a new and restless spirit, seeking violently to burst through old and cramping forms, a nervous preoccupation with perpetually changing inner states of consciousness, a longing for the unbounded and the indefinable, for perpetual movement and change, an effort to return to the forgotten sources of life, a passionate effort at self-assertion both individual and collective, a search after means of expressing an unappeasable yearning for unattainable goals".[19]

Etymology[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The group of words with the root "Roman" in the various European languages, such as "romance" and "Romanesque", has a complicated history, but by the middle of the 18th century "romantic" in English and romantique in French were both in common use as adjectives of praise for natural phenomena such as views and sunsets, in a sense close to modern English usage but without the amorous connotation. The application of the term to literature first became common in Germany, where the circle around the Schlegel brothers, critics August and Friedrich, began to speak of romantische Poesie ("romantic poetry") in the 1790s, contrasting it with "classic" but in terms of spirit rather than merely dating. Friedrich Schlegel wrote in his Dialogue on Poetry (1800), "I seek and find the romantic among the older moderns, in Shakespeare, in Cervantes, in Italian poetry, in that age of chivalry, love and fable, from which the phenomenon and the word itself are derived."[20]

In both French and German the closeness of the adjective to roman, meaning the fairly new literary form of the novel, had some effect on the sense of the word in those languages. The use of the word, invented by Friedrich Schlegel, did not become general very quickly, and was probably spread more widely in France by its persistent use by Germaine de Staël in her De l'Allemagne (1813), recounting her travels in Germany.[21] In England Wordsworth wrote in a preface to his poems of 1815 of the "romantic harp" and "classic lyre",[21] but in 1820 Byron could still write, perhaps slightly disingenuously, "I perceive that in Germany, as well as in Italy, there is a great struggle about what they call 'Classical' and 'Romantic', terms which were not subjects of classification in England, at least when I left it four or five years ago".[22] It is only from the 1820s that Romanticism certainly knew itself by its name, and in 1824 the Académie française took the wholly ineffective step of issuing a decree condemning it in literature.[23]

Period[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The period typically called Romantic varies greatly between different countries and different artistic media or areas of thought. Margaret Drabble described it in literature as taking place "roughly between 1770 and 1848",[24] and few dates much earlier than 1770 will be found. In English literature, M. H. Abrams placed it between 1789, or 1798, this latter a very typical view, and about 1830, perhaps a little later than some other critics.[25] Others have proposed 1780–1830.[26] In other fields and other countries the period denominated as Romantic can be considerably different; musical Romanticism, for example, is generally regarded as only having ceased as a major artistic force as late as 1910, but in an extreme extension the Four Last Songs of Richard Strauss are described stylistically as "Late Romantic" and were composed in 1946–48.[27] However, in most fields the Romantic Period is said to be over by about 1850, or earlier.

The early period of the Romantic Era was a time of war, with the French Revolution (1789–1799) followed by the Napoleonic Wars until 1815. These wars, along with the political and social turmoil that went along with them, served as the background for Romanticism.[28] The key generation of French Romantics born between 1795–1805 had, in the words of one of their number, Alfred de Vigny, been "conceived between battles, attended school to the rolling of drums".[29] According to Jacques Barzun, there were three generations of Romantic artists. The first emerged in the 1790s and 1800s, the second in the 1820s, and the third later in the century.[30]

Context and place in history[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The more precise characterization and specific definition of Romanticism has been the subject of debate in the fields of intellectual history and literary history throughout the 20th century, without any great measure of consensus emerging. That it was part of the Counter-Enlightenment, a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment, is generally accepted in current scholarship. Its relationship to the French Revolution, which began in 1789 in the very early stages of the period, is clearly important, but highly variable depending on geography and individual reactions. Most Romantics can be said to be broadly progressive in their views, but a considerable number always had, or developed, a wide range of conservative views,[31] and nationalism was in many countries strongly associated with Romanticism, as discussed in detail below.

In philosophy and the history of ideas, Romanticism was seen by Isaiah Berlin as disrupting for over a century the classic Western traditions of rationality and the idea of moral absolutes and agreed values, leading "to something like the melting away of the very notion of objective truth",[32] and hence not only to nationalism, but also fascism and totalitarianism, with a gradual recovery coming only after World War II.[33] For the Romantics, Berlin says,

in the realm of ethics, politics, aesthetics it was the authenticity and sincerity of the pursuit of inner goals that mattered; this applied equally to individuals and groups—states, nations, movements. This is most evident in the aesthetics of romanticism, where the notion of eternal models, a Platonic vision of ideal beauty, which the artist seeks to convey, however imperfectly, on canvas or in sound, is replaced by a passionate belief in spiritual freedom, individual creativity. The painter, the poet, the composer do not hold up a mirror to nature, however ideal, but invent; they do not imitate (the doctrine of mimesis), but create not merely the means but the goals that they pursue; these goals represent the self-expression of the artist's own unique, inner vision, to set aside which in response to the demands of some "external" voice—church, state, public opinion, family friends, arbiters of taste—is an act of betrayal of what alone justifies their existence for those who are in any sense creative.[34]

Arthur Lovejoy attempted to demonstrate the difficulty of defining Romanticism in his seminal article "On The Discrimination of Romanticisms" in his Essays in the History of Ideas (1948); some scholars see Romanticism as essentially continuous with the present, some like Robert Hughes see in it the inaugural moment of modernity,[35] and some like Chateaubriand, Novalis and Samuel Taylor Coleridge see it as the beginning of a tradition of resistance to Enlightenment rationalism—a "Counter-Enlightenment"—[36][37] to be associated most closely with German Romanticism. An earlier definition comes from Charles Baudelaire: "Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor exact truth, but in the way of feeling."[38]

The end of the Romantic era is marked in some areas by a new style of Realism, which affected literature, especially the novel and drama, painting, and even music, through Verismo opera. This movement was led by France, with Balzac and Flaubert in literature and Courbet in painting; Stendhal and Goya were important precursors of Realism in their respective media. However, Romantic styles, now often representing the established and safe style against which Realists rebelled, continued to flourish in many fields for the rest of the century and beyond. In music such works from after about 1850 are referred to by some writers as "Late Romantic" and by others as "Neoromantic" or "Postromantic", but other fields do not usually use these terms; in English literature and painting the convenient term "Victorian" avoids having to characterise the period further.

In northern Europe, the Early Romantic visionary optimism and belief that the world was in the process of great change and improvement had largely vanished, and some art became more conventionally political and polemical as its creators engaged polemically with the world as it was. Elsewhere, including in very different ways the United States and Russia, feelings that great change was underway or just about to come were still possible. Displays of intense emotion in art remained prominent, as did the exotic and historical settings pioneered by the Romantics, but experimentation with form and technique was generally reduced, often replaced with meticulous technique, as in the poems of Tennyson or many paintings. If not realist, late 19th-century art was often extremely detailed, and pride was taken in adding authentic details in a way that earlier Romantics did not trouble with. Many Romantic ideas about the nature and purpose of art, above all the pre-eminent importance of originality, remained important for later generations, and often underlie modern views, despite opposition from theorists.

Literature[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

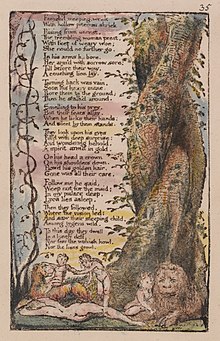

In literature, Romanticism found recurrent themes in the evocation or criticism of the past, the cult of "sensibility" with its emphasis on women and children, the isolation of the artist or narrator, and respect for nature. Furthermore, several romantic authors, such as Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne, based their writings on the supernatural/occult and human psychology. Romanticism tended to regard satire as something unworthy of serious attention, a prejudice still influential today.[39] The romantic movement in literature was preceded by the Enlightenment and succeeded by Realism.

Some authors cite 16th century poet Isabella di Morra as an early precursor of Romantic literature. Her lyrics covering themes of isolation and loneliness, which reflected the tragic events of her life, are considered "an impressive prefigurement of Romanticism",[40] differing from the Petrarchist fashion of the time based on the philosophy of love.

The precursors of Romanticism in English poetry go back to the middle of the 18th century, including figures such as Joseph Warton (headmaster at Winchester College) and his brother Thomas Warton, Professor of Poetry at Oxford University.[41] Joseph maintained that invention and imagination were the chief qualities of a poet. Thomas Chatterton is generally considered the first Romantic poet in English.[42] The Scottish poet James Macpherson influenced the early development of Romanticism with the international success of his Ossian cycle of poems published in 1762, inspiring both Goethe and the young Walter Scott. Both Chatterton and Macpherson's work involved elements of fraud, as what they claimed was earlier literature that they had discovered or compiled was, in fact, entirely their own work. The Gothic novel, beginning with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), was an important precursor of one strain of Romanticism, with a delight in horror and threat, and exotic picturesque settings, matched in Walpole's case by his role in the early revival of Gothic architecture. Tristram Shandy, a novel by Laurence Sterne (1759–67) introduced a whimsical version of the anti-rational sentimental novel to the English literary public.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. «Romanticism. Retrieved 30 January 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online». Britannica.com. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 13 October 2005-ին. Վերցված է 2010-08-24-ին.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Casey, Christopher (October 30, 2008). «"Grecian Grandeurs and the Rude Wasting of Old Time": Britain, the Elgin Marbles, and Post-Revolutionary Hellenism». Foundations. Volume III, Number 1. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից May 13, 2009-ին. Վերցված է 2014-05-14-ին.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ David Levin, History as Romantic Art: Bancroft, Prescott, and Parkman (1967)

- ↑ Gerald Lee Gutek, A history of the Western educational experience (1987) ch. 12 on Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

- ↑ Ashton Nichols, "Roaring Alligators and Burning Tygers: Poetry and Science from William Bartram to Charles Darwin," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 2005 149(3): 304–15

- ↑ Morrow, John (2011). «Romanticism and political thought in the early 19th century» (PDF). In Stedman Jones, Gareth; Claeys, Gregory (eds.). The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought. The Cambridge History of Political Thought. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. էջեր 39–76. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521430562. ISBN 978-0-511-97358-1. Վերցված է 10 September 2017-ին.

- ↑ Perpinya, Núria. Ruins, Nostalgia and Ugliness. Five Romantic perceptions of Middle Ages and a spoon of Game of Thrones and Avant-garde oddity. Berlin: Logos Verlag. 2014

- ↑ "'A remarkable thing,' continued Bazarov, 'these funny old romantics! They work up their nervous system into a state of agitation, then, of course, their equilibrium is upset.'" (Ivan Turgenev, Fathers and Sons, chap. 4 [1862])

- ↑ Szabolcsi, B. (1970). «The Decline of Romanticism: End of the Century, Turn of the Century-- Introductory Sketch of an Essay». Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 12 (1/4): 263. doi:10.2307/901360. JSTOR 901360.

- ↑ Novotny, 96

- ↑ From the Preface to the 2nd edition of Lyrical Ballads, quoted Day, 2

- ↑ Day, 3

- ↑ Ruthven (2001) p. 40 quote: "Romantic ideology of literary authorship, which conceives of the text as an autonomous object produced by an individual genius."

- ↑ Spearing (1987) quote: "Surprising as it may seem to us, living after the Romantic movement has transformed older ideas about literature, in the Middle Ages authority was prized more highly than originality."

- ↑ Eco (1994) p. 95 quote: Much art has been and is repetitive. The concept of absolute originality is a contemporary one, born with Romanticism; classical art was in vast measure serial, and the "modern" avant-garde (at the beginning of this century) challenged the Romantic idea of "creation from nothingness", with its techniques of collage, mustachios on the Mona Lisa, art about art, and so on.

- ↑ Waterhouse (1926), throughout; Smith (1924); Millen, Jessica Romantic Creativity and the Ideal of Originality: A Contextual Analysis, in Cross-sections, The Bruce Hall Academic Journal – Volume VI, 2010 PDF; Forest Pyle, The Ideology of Imagination: Subject and Society in the Discourse of Romanticism (Stanford University Press, 1995) p. 28.

- ↑ 1963–, Breckman, Warren (2008). European Romanticism: A Brief History with Documents. Rogers D. Spotswood Collection. (1st ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martins. ISBN 978-0-312-45023-6. OCLC 148859077.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (օգնություն)CS1 սպաս․ բազմաթիվ անուններ: authors list (link) - ↑ Day 3–4; quotation from M.H. Abrams, quoted in Day, 4

- ↑ Berlin, 92

- ↑ Ferber, 6–7

- ↑ 21,0 21,1 Ferber, 7

- ↑ Christiansen, 241.

- ↑ Christiansen, 242.

- ↑ in her Oxford Companion article, quoted by Day, 1

- ↑ Day, 1–5

- ↑ Mellor, Anne; Matlak, Richard (1996). British Literature 1780–1830. NY: Harcourt Brace & Co./Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1-4130-2253-7.

- ↑ Edward F. Kravitt, The Lied: Mirror of Late Romanticism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996): 47. 0-300-06365-2.

- ↑ Greenblatt et al., Norton Anthology of English Literature, eighth edition, "The Romantic Period – Volume D" (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 2006): [Հղում աղբյուրներին]

- ↑ Johnson, 147, inc. quotation

- ↑ Barzun, 469

- ↑ Day, 1–3; the arch-conservative and Romantic is Joseph de Maistre, but many Romantics swung from youthful radicalism to conservative views in middle age, for example Wordsworth. Samuel Palmer's only published text was a short piece opposing the Repeal of the corn laws.

- ↑ Berlin, 57

- ↑ Several of Berlin's pieces dealing with this theme are collected in the work referenced. See in particular: Berlin, 34–47, 57–59, 183–206, 207–37.

- ↑ Berlin, 57–58

- ↑ Linda Simon The Sleep of Reason by Robert Hughes

- ↑ Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder, Pimlico, 2000 0-7126-6492-0 was one of Isaiah Berlin's many publications on the Enlightenment and its enemies that did much to popularise the concept of a Counter-Enlightenment movement that he characterised as relativist, anti-rationalist, vitalist and organic,

- ↑ Darrin M. McMahon, "The Counter-Enlightenment and the Low-Life of Literature in Pre-Revolutionary France" Past and Present No. 159 (May 1998:77–112) p. 79 note 7.

- ↑ «Baudelaire's speech at the "Salon des curiosités Estethiques» (ֆրանսերեն). Fr.wikisource.org. Վերցված է 2010-08-24-ին.

- ↑ Sutherland, James (1958) English Satire p. 1. There were a few exceptions, notably Byron, who integrated satire into some of his greatest works, yet shared much in common with his Romantic contemporaries. Bloom, p. 18.

- ↑ Paul F. Grendler, Renaissance Society of America, Encyclopedia of the Renaissance, Scribner, 1999, p. 193

- ↑ John Keats. By Sidney Colvin, p. 106. Elibron Classics

- ↑ Thomas Chatterton, Grevel Lindop, 1972, Fyffield Books, p. 11