«Մասնակից:GrigorGB/Ավազարկղ»–ի խմբագրումների տարբերություն

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Տող 45. | Տող 45. | ||

Հետագայում ստեղծվել են այլ զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացներ մատուցողներ: Մարի Վաշինգթոնի համալսարանից Ջիմ Գրումը և Մայքլ Բրենսոնը Նյու Յորքի քաղաքային համալսարանի Յորք քոլեջից, տեղակայել են զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացները մի քանի համալսարաններում: Սկզբնական զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացները հիմնված չէին տեղադրված նյութերի, ուսուցման կառավարման համակարգերի և այնպիսի համակարգերի վրա, որոնք համատեղում են ուսուցման կառավարման համակարգերը ավելի ազատ ինտերնետային ռեսուրսների հետ<ref name=Masters2011>{{cite journal|last=Masters|first=Ken|title=A brief guide to understanding MOOCs|journal=The Internet Journal of Medical Education|year=2011|volume= 1|issue=Num. 2|url=http://ispub.com/IJME/1/2/10995}}</ref>: Զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացները, որպես մասնավոր և ոչ առևտրային ինստիտուտներ, կարևորում էին հանրահայտ ֆակուլտետների դասախոսներին և ընդլայնում առկա հեռահար ուսուցման առաջարկները (օրինակ՝ ձայնագրություններ) դաձնելով դրանք անվճար և ազատ առցանց<ref>The College of St. Scholastica, "[http://go.css.edu/learn Massive Open Online Courses]", (2012)</ref>: |

Հետագայում ստեղծվել են այլ զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացներ մատուցողներ: Մարի Վաշինգթոնի համալսարանից Ջիմ Գրումը և Մայքլ Բրենսոնը Նյու Յորքի քաղաքային համալսարանի Յորք քոլեջից, տեղակայել են զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացները մի քանի համալսարաններում: Սկզբնական զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացները հիմնված չէին տեղադրված նյութերի, ուսուցման կառավարման համակարգերի և այնպիսի համակարգերի վրա, որոնք համատեղում են ուսուցման կառավարման համակարգերը ավելի ազատ ինտերնետային ռեսուրսների հետ<ref name=Masters2011>{{cite journal|last=Masters|first=Ken|title=A brief guide to understanding MOOCs|journal=The Internet Journal of Medical Education|year=2011|volume= 1|issue=Num. 2|url=http://ispub.com/IJME/1/2/10995}}</ref>: Զանգվածային բաց առցանց դասընթացները, որպես մասնավոր և ոչ առևտրային ինստիտուտներ, կարևորում էին հանրահայտ ֆակուլտետների դասախոսներին և ընդլայնում առկա հեռահար ուսուցման առաջարկները (օրինակ՝ ձայնագրություններ) դաձնելով դրանք անվճար և ազատ առցանց<ref>The College of St. Scholastica, "[http://go.css.edu/learn Massive Open Online Courses]", (2012)</ref>: |

||

=== Recent developments === |

=== Recent developments === |

||

| Տող 57. | Տող 59. | ||

According to [[The New York Times]], 2012 became "the year of the MOOC" as several well-financed providers, associated with top universities, emerged, including [[Coursera]], [[Udacity]], and [[edX]].<ref name=pappano>{{cite web|last=Pappano|first=Laura|title=The Year of the MOOC|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0|publisher=The New York Times|accessdate=18 April 2014}}</ref><ref name="educationdive.com">Smith, Lindsey "[http://www.educationdive.com/news/5-mooc-providers/44506/ 5 education providers offering MOOCs now or in the future]". 31 July 2012.</ref> |

According to [[The New York Times]], 2012 became "the year of the MOOC" as several well-financed providers, associated with top universities, emerged, including [[Coursera]], [[Udacity]], and [[edX]].<ref name=pappano>{{cite web|last=Pappano|first=Laura|title=The Year of the MOOC|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0|publisher=The New York Times|accessdate=18 April 2014}}</ref><ref name="educationdive.com">Smith, Lindsey "[http://www.educationdive.com/news/5-mooc-providers/44506/ 5 education providers offering MOOCs now or in the future]". 31 July 2012.</ref> |

||

==== North America ==== |

|||

Several well-financed American providers emerged, associated with top universities, including [[Udacity]], [[Coursera]], [[edX]],<ref name="educationdive.com"/> |

|||

In the fall of 2011 Stanford University launched three courses.<ref name=NYT71712>{{cite news |title=Top universities test the online appeal of free |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/18/education/top-universities-test-the-online-appeal-of-free.html |accessdate=18 July 2012|newspaper=The New York Times|date=17 July 2012|author=Richard Pérez-Peña}}</ref> The first of those courses was ''Introduction Into AI'', launched by [[Sebastian Thrun]] and [[Peter Norvig]]. Enrollment quickly reached 160,000 students. The announcement was followed within weeks by the launch of two more MOOCs, by [[Andrew Ng]] and [[Jennifer Widom]]. Following the publicity and high enrollment numbers of these courses, Thrun started a company he named Udacity and [[Daphne Koller]] and [[Andrew Ng]] launched Coursera. Coursera subsequently announced university partnerships with [[University of Pennsylvania]], [[Princeton University]], [[Stanford University]] and [[The University of Michigan]]. |

|||

Concerned about the commercialization of online education, MIT created the not-for-profit MITx. The inaugural course, 6.002x, launched in March 2012. [[Harvard]] joined the group, renamed [[edX]], that spring, and [[University of California, Berkeley]] joined in the summer. The initiative then added the [[University of Texas System]], [[Wellesley College]] and [[Georgetown University]]. |

|||

In November 2012, the [[University of Miami]] launched its first high school MOOC as part of Global Academy, its online high school. The course became available for high school students preparing for the [[SAT]] Subject Test in biology.<ref>{{cite news |title=History of a revolution in e-learning |url=http://revistaeducacionvirtual.com/cronologia-de-la-revolucion-de-la-educacion-2012-desde-opencourseware-y-khan-hasta-coursera-wedubox-y-udacity/ |accessdate=10 August 2012|newspaper=Revista Educacion Virtual|author=Horacio Reyes}}</ref> |

|||

In January 2013, Udacity launched its first MOOCs-for-credit, in collaboration with [[San Jose State University]]. In May 2013 the company announced the first entirely MOOC-based Master's Degree, a collaboration between Udacity, AT&T and the [[Georgia Institute of Technology]], costing $7,000, a fraction of its normal tuition.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/troyonink/2013/05/15/georgia-tech-udacity-shock-higher-ed-with-7000-degree/ |title=Georgia Tech, Udacity Shock Higher Ed With $7,000 Degree |publisher=Forbes |date=2012-04-18 |accessdate=2013-05-30}}</ref> |

|||

"Gender Through Comic Books," was a course taught by [[Ball State University]]'s Christina Blanch on [[Instructure]]'s Canvas Network, a MOOC platform launched in November 2012.<ref name=comicbook>{{cite web|last=Burlingame|first=Russ|title=Teaching Gender Through Comics With Christina Blanch, Part 1|url=http://comicbook.com/blog/2013/03/23/teaching-gender-through-comics-with-christina-blanch/|publisher=Comic Book}}</ref> The course used examples from [[comic books]] to teach academic concepts about gender and perceptions.<ref name=digitalspy>{{cite web|last=Armitage|first=Hugh|title=Christina Blanch (Gender Through Comic Books) on teaching with comics|url=http://www.digitalspy.com/comics/interviews/a454002/christina-blanch-gender-through-comic-books-on-teaching-with-comics.html|publisher=Digital Spy}}</ref> |

|||

In March 2013, Coursolve piloted a [[crowdsourced]] business strategy course for 100 organizations with the [[University of Virginia]].<ref>{{cite web|author=Zafrin Nurmohamed, Nabeel Gillani, and Michael Lenox |url=http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2013/07/a_new_use_for_moocs_real-world.html |title=A New Use for MOOCs: Real-World Problem Solving |publisher=Harvard Business Review blog |date=2013-07-04 |accessdate=2013-07-08}}</ref> A data science MOOC began in May 2013.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://trust.guidestar.org/2013/04/25/connect-with-students-to-mooc-source-your-data/ |title=Connect with students to "MOOC-source" your data |publisher=GuideStar Trust blog |date=2013-04-25 |accessdate=2013-07-08 |author=Amit Jain}}</ref> |

|||

In May 2013 Coursera announced free e-books for some courses in partnership with [[Chegg]], an online textbook-rental company. Students would use Chegg's [[e-reader]], which limits copying and printing and could use the book only while enrolled in the class.<ref name=etext>{{cite news|last=New|first=Jake|title=Partnership Gives Students Access to a High-Price Text on a MOOC Budget|url=http://chronicle.com/article/Partnership-Gives-Students/139109/|accessdate=14 May 2013|newspaper=Chronicle of Higher Education|date=8 May 2013}}</ref> |

|||

In June 2013, the [[University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill]] launched Skynet University,<ref>{{cite web|title=Skynet University|url=http://skynet.unc.edu/introastro/faqs}}</ref> which offers MOOCs on introductory astronomy. Participants gain access to the university's global network of [[robotic telescope]]s, including those in the Chilean Andes and Australia. It incorporates [[YouTube]],<ref>{{cite web|title=Skynet University on YouTube|url={{youtube user|introastro|Introduction to Astronomy}}}}</ref> [[Facebook]]<ref>{{cite web|title=Skynet on Facebook|url={{facebook page|SkynetRTN}}}}</ref> and [[Twitter]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Skynet on Twitter|url={{twitter.com|SkynetRTN}}}}</ref> |

|||

In September 2013, edX announced a partnership with Google to develop Open edX, an [[open source]] platform and its MOOC.org, a site for non-[[xConsortium]] groups to build and host courses. Google will work on the core platform development with edX partners. In addition, Google and edX will collaborate on research into how students learn and how technology can transform learning and teaching. MOOC.org will adopt Google's infrastructure.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.edx.org/alert/edx-announces-partnership-google/1115 |title=Announces Partnership with Google to Expand Open Source Platform |publisher=edX |date=2013-09-10 |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> |

|||

EdX currently offers 94 courses from 29 institutions around the world (as of November 2013). During its first 13 months of operation (ending March 2013), Coursera offered about 325 courses, with 30% in the sciences, 28% in arts and humanities, 23% in information technology, 13% in business and 6% in mathematics.<ref name="SA31313" /> Udacity offered 26 courses. Udacity's CS101, with an enrollment of over 300,000 students, was the largest MOOC to date. |

|||

Some organisations operate their own MOOCs – including Google's Power Search. As of February 2013 dozens of universities had affiliated with MOOCs, including many international institutions.<ref name="NYT022013">{{cite news|title=Universities Abroad Join Partnerships on the Web|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/21/education/universities-abroad-join-mooc-course-projects.html|accessdate=21 February 2013|newspaper=The New York Times|date=20 February 2013|author=Tamar Lewin}}</ref><ref name=CHE022113>{{cite news|title=Competing MOOC Providers Expand into New Territory—and Each Other's|url=http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/competing-mooc-providers-expand-into-new-territory-and-each-others/42463|accessdate=21 February 2013|newspaper=The Chronicle of Higher Education|date=21 February 2013|author=Steve Kolowich|format=blog by expert journalist}}</ref> |

|||

As of May 2014, more than 900 MOOCs are offered by US universities and colleges: [[List of MOOCs offered by US universities]]. |

|||

==== Asia ==== |

|||

Schools in Japan provide MOOCs.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://schoo.jp/ |title=schoo(スクー) WEB-campus |publisher=Schoo.jp |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref><ref name="CHE8513"/> |

|||

The first MOOC in Malaysia was offered by [[Taylor's University]] in March 2013. This MOOC can be found at https://www.openlearning.com/courses/Entrepreneurship . The MOOC was titled "Entrepreneurship" and it attracted students from 115 different countries. Following this successful MOOC, Taylor's University launched the second MOOC titled "Achieving Success with Emotional Intelligence" https://www.openlearning.com/courses/Success<ref>1. Al-Atabi, M.T. and DeBoer, J. 2014 "Teaching Entrepreneurship using Massive Open Online Course (MOOC)." Technovation. In Press.</ref> in July 2013. In August 2013, Universitas Ciputra Entrepreneurship Online (UCEO) launched first MOOC in Indonesia with the first course entitled Entrepreneurship Ciputra Way.<ref>{{cite web | title = Kuliah? Di UCEO saja|publisher=Bisnis.com |author=Inda Marlina|date = 2013-08-24 |accessdate=2013-10-23| url = http://news.bisnis.com/read/20130824/255/158567/kuliah-di-uceo-saja}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = |

|||

Mau Belajar Jadi Pengusaha Secara Gratis? Ini Caranya|publisher=detik.com|author=Wiji Nurhayat| date = 2013-08-25 |accessdate=2013-10-23| url = http://finance.detik.com/read/2013/08/25/103637/2339721/4/mau-belajar-jadi-pengusaha-secara-gratis-ini-caranya}}</ref> With over 20,000 registered members, the course offered insights on how to start a business, and was delivered in Indonesian. |

|||

==== Europe ==== |

|||

In January 2012, University of Helsinki launched a Finnish MOOC in programming. The MOOC is used as a way to offer high-schools the opportunity to provide programming courses for their students, even if no local premises or faculty that can organize such courses exist.<ref name="VihavainenMOOC2012">{{Cite doi|10.1145/2380552.2380603}}</ref> The course has been offered recurringly, and the top-performing students are admitted to a BSc and MSc program in Computer Science at the University of Helsinki.<ref name="VihavainenMOOC2012"/><ref>{{cite web|title=MOOC dot Fi - Massive Open Online Courses|url=http://mooc.fi|website=http://mooc.fi}}</ref> At a meeting on E-Learning and MOOCs, Jaakko Kurhila, Head of studies for University of Helsinki, Department of Computer Science, claimed that to date, there has been over 8000 participants in their MOOCs altogether.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Kurhila|first1=Jaakko|title=Experiences from running a programming MOOC in Finland|url=http://www.aalto.fi/en/current/events/digi_breakfast_on-e-learning_and_moocs/|website=http://www.aalto.fi/en/current/events/digi_breakfast_on-e-learning_and_moocs/|accessdate=27 August 2014}}</ref> |

|||

In February 2012, ex-Nokia employees in Finland based CBTec launched Eliademy.com,<ref>http://www.Eliademy.com</ref> based on the Open Source [[Moodle]] [[Virtual learning environment]].<ref name="techcrunch1">{{cite web|author=Tuesday, 12 March 2013 |url=http://techcrunch.com/2013/03/12/eliademy/ |title=MeeGo To MOOCs, Ex-Nokians Launch Eliademy To Put Education In The Cloud |publisher=TechCrunch |date=2013-03-12 |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> The site is localized to more than 19 languages (including Latin), designed for mobile use.<ref name="techcrunch1"/><ref>{{cite web|author=Sotiris says: |url=http://www.moodlenews.com/2013/another-look-at-eliademy-a-free-alternative-to-moodle/ |title=Another Look at Eliademy, a cloud-based alternative to Moodle | Moodle News |publisher=Moodlenews.com |date=2013-08-02 |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> |

|||

In late 2012, the UK's [[Open University]] launched a British MOOC provider, [[Futurelearn]], as a separate company<ref>{{cite web|author=Claire Shaw |url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/higher-education-network/blog/2012/dec/20/futurelearn-uk-moocs-martin-bean |title=FutureLearn is UK's chance to 'fight back', says OU vice-chancellor | Higher Education Network | Guardian Professional |publisher=Guardian |date=2012-12-20|accessdate=2013-05-30}}</ref> including provision of MOOCs from non-university partners.<ref>{{cite web|author=Tuesday, 19 February 2013 |url=http://techcrunch.com/2013/02/19/u-k-moocs-alliance-futurelearn-adds-five-more-universities-and-the-british-library-now-backed-by-18-partners/ |title=U.K. MOOCs Alliance, Futurelearn, Adds Five More Universities And The British Library — Now Backed By 18 Partners |publisher=TechCrunch |date=2013-02-19|accessdate=2013-05-30}}</ref> |

|||

On 15 March 2012 Researchers Dr. Jorge Ramió and Dr. Alfonso Muñoz from Universidad Politécnica de Madrid successfully launched the first Spanish MOOC titled Crypt4you.{{Citation needed|reason=reliable source needed for the whole sentence|date=August 2013}} |

|||

[[iversity]] is a MOOC provider in Germany.<ref name=NYT022013/> With over 82,000 students (Nov 2013) iversity's "The Future of Storytelling" is Europe's largest MOOC to date. |

|||

OpenupEd<ref>[http://www.openuped.eu/ OpenupEd]</ref> is a supranational platform, founded with support of the [[European Union]] (EU).<ref name=CHE8513>{{cite news|title=American MOOC Providers Face International Competition|url=https://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/american-mooc-providers-face-international-competition/44637|accessdate=8 July 2013|newspaper=The Chronicle of Higher Education|date=5 July 2013|author=Sara Grossman}}</ref> |

|||

In Ireland [[ALISON (company)|ALISON]] provides free online certificate/diploma courses to two 2 million learners worldwide.<ref name="CHE8513"/> ALISON was shortlisted in June 2013 by London–based [[education technology]] company Edxus Group and specialist media and advisory firm IBIS Capital, as one of the 'top 20 e-learning companies in Europe' as judged by an expert panel.<ref name=EDXUS>{{cite web|title=Europe's 20 Fastest Growing And Most Innovative E-Learning Companies Named|url=http://edxusgroup.com/europes-20-fastest-growing-and-most-innovative-e-learning-companies-named-2/|work=Edxus Group News|publisher=Edxus Group|accessdate=1 August 2013}}</ref> |

|||

In the UK of summer 2013, [http://www.physio-pedia.com/ Physiopedia] ran their first MOOC regarding [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Professional_Ethics_Course/ Professional Ethics] in collaboration with [http://www.uwc.ac.za/Faculties/CHS/physiotherapy/Pages/default.aspx/ University of the Western Cape] in South Africa. This was followed by a second course in 2014, [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Physiotherapy_Management_of_Spinal_Cord_Injuries/ Physiotherapy Management of Spinal Cord Injuries], which was accredited by the [http://www.wcpt.org/ WCPT] and attracted approximately 4000 participants with a 40% completion rate. [http://www.physio-pedia.com/ Physiopedia] is the first provider of physiotherapy/physical therapy MOOCs, accessible to participants worldwide. |

|||

In October 2013, the French government announced the creation of [http://www.france-universite-numerique.fr/ France Universite Numerique] (FUN), a French public alternative to existing solutions. French business schools have begun launching their own MOOCs, the first being supervised by [[Alberto Alemanno]]. |

|||

==== Australia ==== |

|||

On 15 October 2012 The [[University of New South Wales]] launched UNSW Computing 1, the first Australian MOOC.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.afr.com/p/national/education/brave_new_free_online_course_for_M7usoay0z7L30BKu3EhIWN |title=Brave new free online course for UNSW |publisher=Afr.com |accessdate=3 June 2013}}</ref> The course was initiated [[OpenLearning]], an online learning platform developed in Australia, which provides features for group work, automated marking, collaboration and [[gamification]].<ref>{{cite web|last=Bernhardt|first=Ingo|title=http://theconversation.com/openlearning-launches-into-competitive-moocs-market-10155|url=http://theconversation.com/openlearning-launches-into-competitive-moocs-market-10155|publisher=The Conversation|accessdate=3 December 2013}}</ref> |

|||

In March 2013 the Open2Study platform was set up in Australia.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.prnewswire.co.uk/news-releases/australia-sets-the-scene-for-free-online-education-199244401.html |title=PR Newswire UK: Australia sets the scene for free online education - MELBOURNE, Australia, 20 March 2013 /PRNewswire/ |location=australia |publisher=Prnewswire.co.uk |accessdate=2013-05-30}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://theconversation.com/the-aussie-coursera-a-new-homegrown-mooc-platform-arrives-12949|title=The Aussie Coursera? A new homegrown MOOC platform arrives |publisher=Theconversation.com|accessdate=2013-05-30}}</ref> |

|||

In July 2013 the Wicking Centre at the [[University of Tasmania]] launched ''Understanding Dementia'', the world's first Dementia MOOC. With one of the world's highest completion rates (39%),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.katyjordan.com/MOOCproject.html |title=MOOC Completion Rates|publisher=katyjordan.com |accessdate=2014-03-19}}</ref> the course was recognized in the journal [[Nature (journal)|Nature]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v505/n7481/full/505026a.html |title=Online education: Targeted MOOC captivates students |publisher=Nature |accessdate=2014-03-19}}</ref> |

|||

==== Latin America ==== |

|||

In 18 June 2012, Ali Lemus from [[Galileo University]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.galileo.edu/ |title=Universidad Galileo |publisher=Galileo.edu |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> launched the first Latin American MOOC titled "Desarrollando Aplicaciones para iPhone y iPad"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.galileo.edu/fisicc/courseware/api-iphone/ |title=Desarrollando Aplicaciones para iPhone y iPad | FISICC |publisher=Galileo.edu |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> This MOOC is a Spanish remix of Stanford University's popular "CS 193P iPhone Application Development" and had 5,380 students enrolled. The technology used to host the MOOC was the Galileo Educational System platform (GES) which is based on the .LRN project.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dotlrn.org/ |title=LRN Home |publisher=Dotlrn.org |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> |

|||

Startup Veduca<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.veduca.com.br/home/index |title=Educação de qualidade ao alcance de todos |publisher=Veduca |date=2013-08-11 |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> launched the first MOOCs in Brazil, in partnership with the [[University of São Paulo]] in June 2013. The first two courses were Basic Physics, taught by Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato, and Probability and Statistics, taught by Melvin Cymbalista and André Leme Fleury.<ref>Latin America's First MOOC (17 June 2013). https://www.edsurge.com/n/2013-06-17-latin-america-s-first-mooc (Retrieved 2 July 2013).</ref> In the first two weeks following the launch at [[Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo]], more than 10,000 students enrolled.<ref name="CHE8513"/><ref>Primeiro curso superior virtual da América Latina já soma 10 mil inscritos (28 June 2013). http://noticias.terra.com.br/educacao/primeiro-curso-superior-virtual-da-america-latina-ja-soma-10-mil-inscritos,2a26b78c2b28f310VgnCLD2000000ec6eb0aRCRD.html (Retrieved 2 July 2013).</ref> |

|||

Startup Wedubox (Finalist at MassChallenge 2013) <ref>{{cite web|url=http://masschallenge.org/blog/wedubox-and-masschallenge-0 |title=Wedubox first massive online platform in Latam and MassChallenge |publisher=MassChallenge |date=2013-08-11 |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> launched the first MOOC in finance and third MOOC in Latam, the MOOC was created by Jorge Borrero (MBA Universidad de la Sabana) with the title "WACC and the cost of capital" it reached 2.500 students in Dec 2013 only 2 months after the launch. |

|||

=== Related educational practices and courses === |

|||

MOOCs can vary by criterion such as being for profit/non-profit or being taught by professors from universities and organizations. [[Khan Academy]], [[Peer-to-Peer University]] (P2PU), [[Udemy]], and [[Course Hero]] are viewed as similar to MOOCs work outside the university system or emphasize individual self-paced lessons.<ref name="CETIS78">Yuan, Li, and Stephen Powell. [http://publications.cetis.ac.uk/2013/667 MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education White Paper]. University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013. pp. 7–8.</ref><ref name=Chronicle>{{cite news|title=What You Need to Know About MOOCs|url=http://chronicle.com/article/What-You-Need-to-Know-About/133475/|accessdate=14 March 2013|newspaper=[[Chronicle of Higher Education]]}}</ref><ref name=DavidBornstein>{{cite news|title=Open Education for a global economy|url=http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/11/open-education-for-a-global-economy}}</ref> Udemy allows teachers to sell online courses, with the course creators keeping 70–85% of the proceeds and [[intellectual property rights]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.udemy.com/teach |title=Teach Online - Join the 1000s of Instructors Teaching on Udemy! |publisher=Udemy.com |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Carey |first=Kevin |url=http://chronicle.com/article/Revenge-of-the-Underpaid/131919/ |title=Revenge of the Underpaid Professors |work=The Chronicle of Higher Education |date=2012-05-20 |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> |

|||

== Structures and instructional design approaches == |

|||

{{external media | width = 210px | align = right |

|||

| headerimage=[[File:Duke Chapel spire.jpg|210px]] |

|||

| video1 = {{youtube|id=JKbPNx2TSgM|title=10 Steps to Developing an Online Course: Walter Sinnott-Armstrong}}, [[Duke University]]<ref name="Duke U">{{cite web | title =10 Steps to Developing an Online Course: Walter Sinnott-Armstrong | work = | publisher =[[Duke University]] | url ={{youtube|id=JKbPNx2TSgM}} | accessdate =20 March 2013 }}</ref> |

|||

| video2 = [http://www.slideshare.net/gsiemens/designing-and-running-a-mooc Designing, developing and running (Massive) Online Courses] by [[George Siemens]], [[Athabasca University]]<ref name="Atha U">{{cite web | title =Designing, developing and running (Massive) Online Courses by George Siemens | work = | publisher =[[Athabasca University]] | date =12 September 2012 | url =http://www.slideshare.net/gsiemens/designing-and-running-a-mooc | accessdate =26 March 2013 }}</ref> }} |

|||

Many MOOCs use video [[lecture]]s, employing the old form of teaching using a new technology.<ref name=EReality>{{cite news|last=Shirky|first=Clay|title=MOOCs and Economic Reality|url=http://chronicle.com/blogs/conversation/2013/07/08/moocs-and-economic-reality/|accessdate=8 July 2013|newspaper=The Chronicle of Higher Education|date=8 July 2013}}</ref> [[Sebastian Thrun|Thrun]] testified before the [[President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology]] (PCAST) that MOOC "courses are 'designed to be challenges,' not lectures, and the amount of data generated from these assessments can be evaluated 'massively using machine learning' at work behind the scenes. This approach, he said, dispels 'the medieval set of myths' guiding teacher efficacy and student outcomes, and replaces it with evidence-based, 'modern, data-driven' educational methodologies that may be the instruments responsible for a 'fundamental transformation of education' itself".<ref name="Librarians and the Era of the MOOC">{{cite news|title=Librarians and the Era of the MOOC|url=http://www.scilogs.com/scientific_and_medical_libraries/librarians-and-the-era-of-the-mooc/|accessdate=11 May 2013|journal=[[Nature.com]]|date=9 May 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Because of massive enrollments, MOOCs require instructional design that facilitates large-scale feedback and interaction. The two basic approaches are: |

|||

* Peer-review and group collaboration |

|||

* Automated feedback through objective, online assessments, e.g. quizzes and exams |

|||

So-called connectivist MOOCs rely on the former approach; broadcast MOOCs rely more on the latter.<ref>Carson, Steve. "[http://tofp.wordpress.com/2012/07/23/what-we-talk-about-when-we-talk-about-automated-assessment/ What we talk about when we talk about automated assessment]" 23 July 2012</ref> This marks a key distinction between [[Massive open online course#Connectivist design|cMOOCs]] where the 'C' stands for 'connectivist', and xMOOCs where the x stands for extended (as in TEDx, EdX) and represents that the MOOC is designed to be in addition to something else (university courses for example).<ref name="xMOOC def">{{cite web | url=https://plus.google.com/109526159908242471749/posts/LEwaKxL2MaM | title=What the 'x' in 'xMOOC' stands for | date=9 April 2013 | accessdate=17 May 2014 | author=Downes, Stephen}}</ref> |

|||

An emerging trend in MOOCs is the use of nontraditional textbooks such as [[graphic novels]] to improve knowledge retention.<ref>{{cite web|last=Price|first=Matthew |url=http://newsok.com/first-massive-open-online-course-at-university-of-oklahoma-to-feature-graphic-novel/article/3759503?custom_click=lead_story_title |title=First massive open online course at University of Oklahoma to feature graphic novel |publisher=The Oklahoman |date=1 March 2013 |accessdate=2013-03-01}}</ref> Others view the videos and other material produced by the MOOC as the next form of the textbook. "MOOC is the new textbook," according to David Finegold of [[Rutgers University]].<ref>{{cite web|last=Young|first=Jeffrey R.|title=The Object Formerly Known as the Textbook|url=http://chronicle.com/article/Dont-Call-Them-Textbooks/136835/|publisher=[[Chronicle of Higher Education]]|accessdate=14 March 2013|date=27 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

=== Connectivist design === |

|||

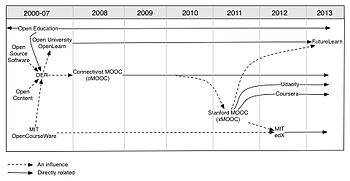

[[File:Figure 1 MOOCs and Open Education Timeline p6.jpg|thumb|left || upright=1.6|Development of MOOC providers<ref>[http://publications.cetis.ac.uk/2013/667 Yuan, Li, and Stephen Powell. MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education White Paper. University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013. p.6]</ref>]] |

|||

As MOOCs have evolved, there appear to be two distinct types: those that emphasize the connectivist philosophy, and those that resemble more traditional courses. To distinguish the two, [[Stephen Downes]] proposed the terms "cMOOC" and "xMOOC".<ref>{{cite web|last=Siemens|first=George |url=http://www.elearnspace.org/blog/2012/07/25/moocs-are-really-a-platform/ |title=MOOCs are really a platform |publisher=Elearnspace |accessdate=2012-12-09}}</ref> A third type, the "vMOOC", has been suggested<ref>{{cite web|last=Wise|first=James |url=http://thinkoutloudclub.com/six-tools-help-vocational-mooc-development/ |title=Six tools to help vocational MOOC development |publisher=ThinkOutLoudClub |accessdate=2012-03-28}}</ref> to describe [[Vocational education|vocational]] MOOCs, that would require [[Simulations#Computer simulation|simulations]] and related technologies to teach and assess practical skills and abilities. |

|||

Such instructional design approaches attempt to connect learners to each other to answer questions and/or collaborate on joint projects. This may include emphasizing collaborative development of the MOOC.<ref>{{cite web|url={{youtube|idv=VMfipxhT_Co}} |title=George Siemens on Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) |publisher=YouTube |date= |accessdate=2012-09-18}}</ref> |

|||

==== Principles ==== |

|||

Connectivist MOOCs are based on principles from [[Connectivism|connectivist pedagogy]]:<ref>Downes, Stephen [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/stephen-downes/connectivism-and-connecti_b_804653.html "'Connectivism' and Connective Knowledge"], Huffpost Education, 5 January 2011, accessed 27 July 2011</ref><ref>Kop, Rita [http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/882 "The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course"], International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, Volume 12, Number 3, 2011, accessed 22 November 2011</ref><ref>Bell, Frances [http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/902/1664 "Connectivism: Its Place in Theory-Informed Research and Innovation in Technology-Enabled Learning"], International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, Volume 12, Number 3, 2011, accessed 31 July 2011</ref><ref>Downes, Stephen. [http://it.coe.uga.edu/itforum/paper92/paper92.html "Learning networks and connective knowledge"], Instructional Technology Forum, 2006, accessed 31 July 2011</ref> |

|||

# ''Aggregation''. Enable content to be produced in different places and aggregated as a newsletter or a web page accessible to participants. |

|||

# ''[[Remix#Broader context|Remixing]]'' associates materials created within the course with each other and with other materials. |

|||

# ''Re-purposing'' of aggregated and remixed materials to suit the goals of each participant. |

|||

# ''Feeding forward'', sharing of re-purposed ideas and content with other participants and the rest of the world. |

|||

An earlier list (2005) of Connectivist principles from Siemens:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/934 |title=Dialogue and connectivism: A new approach to understanding and promoting dialogue-rich networked learning | Ravenscroft | The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning |publisher=Irrodl.org |accessdate=2012-09-18}}</ref> |

|||

# Learning and knowledge rest in diversity of opinions. |

|||

# Learning is a process of connecting specialised nodes or information sources. |

|||

# Learning may reside in non-human appliances. |

|||

# Capacity to learn is more critical than what is currently known. |

|||

# Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate learning. |

|||

# Ability to see connections between fields, ideas and concepts is a core skill. |

|||

# Accurate, up-to-date knowledge is the intent of all connectivist learning activities. |

|||

# Decision making is a learning process. Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality. While there is a right answer now, it may be wrong tomorrow due to alterations in the information climate affecting the decision.{{clarify|date=October 2013}} |

|||

Ravenscroft claimed that connectivist MOOCs better support collaborative dialogue and knowledge building.<ref name="Ravenscroft">Dialogue and Connectivism: A New Approach to Understanding and Promoting Dialogue-Rich Networked Learning [http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/934] Andrew Ravenscroft International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning Vol. 12.3 March – 2011, Learning Technology Research Institute (LTRI), London Metropolitan University, UK</ref><ref name="Mak Williams Mackness">S.F. John Mak, R. Williams, and J. Mackness, [http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fss/organisations/netlc/past/nlc2010/abstracts/PDFs/Mak.pdf Blogs and Forums as Communication and Learning Tools in a MOOC], Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networked Learning (2010)</ref> |

|||

=== Assessments === |

|||

Assessment can be the most difficult activity to conduct online, and online assessments can be quite different from the bricks-and-mortar version.<ref name="DoF 1">[http://degreeoffreedom.org/mooc-components-assessment/ Degree of Freedom – an adventure in online learning], ''MOOC Components – Assessment'', 22 March 2013.</ref> Special attention has been devoted to proctoring and cheating.<ref name=NYT030212>{{cite news|last=Eisenberg|first=Anne|title=Keeping an Eye on Online Test-Takers|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/03/technology/new-technologies-aim-to-foil-online-course-cheating.html?_r=1&|accessdate=19 April 2013|newspaper=New York Times|date=2 March 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The two most common methods of MOOC assessment are machine-graded multiple-choice quizzes or tests and peer-reviewed written assignments.<ref name="DoF 1"/> Machine grading of written assignments is also underway.<ref name="IHE 1"/> |

|||

Peer review is often based upon sample answers or [[Rubric (academic)|rubrics]], which guide the grader on how many points to award different answers. These rubrics cannot be as complex for peer grading as for teaching assistants. Students are expected to learn via grading others<ref>{{cite web|last=Wong|first=Michael|title=Online Peer Assessment in MOOCs: Students Learning from Students|url=http://ctlt.ubc.ca/2013/03/28/online-peer-assessment-in-moocs-students-learning-from-students/|work=Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology Newsletter|publisher=University of British Columbia|accessdate=20 April 2013|date=28 March 2013}}</ref> and become more engaged with the course.<ref name="in AIS Electronic Library AISeL">P. Adamopoulos, "What Makes a Great MOOC? An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Student Retention in Online Courses," ''ICIS 2013 Proceedings'' (2013) pp. 1–21 [http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2013/proceedings/BreakthroughIdeas/13/ in AIS Electronic Library (AISeL)]</ref> Exams may be proctored at regional testing centers. Other methods, including "eavesdropping technologies worthy of the C.I.A." allow testing at home or office, by using webcams, or monitoring mouse clicks and typing styles.<ref name=NYT030212/> |

|||

Special techniques such as [[Computerized adaptive testing|adaptive testing]] may be used, where the test tailors itself given the student's previous answers, giving harder or easier questions accordingly. |

|||

===Lecture design=== |

|||

A study of edX student habits found that certificate-earning students generally stop watching videos longer than 6 to 9 minutes. They viewed the first 4.4 minutes (median) of 12- to 15-minute videos. |

|||

==Completion rates== |

|||

Completion rates are typically lower than 10%, with a steep participation drop starting in the first week. In the course ''Bioelectricity, Fall 2012'' at Duke University, 12,725 students enrolled, but only 7,761 ever watched a video, 3,658 attempted a quiz, 345 attempted the final exam, and 313 passed, earning a certificate.<ref>{{cite web|last=Catropa|first=Dayna|title=Big (MOOC) Data|url=http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/stratedgy/big-mooc-data|work=Inside Higher Ed|accessdate=27 March 2013|date=24 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Jordan|first=Katy|title=MOOC Completion Rates: The Data|url=http://www.katyjordan.com/MOOCproject.html|accessdate=23 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Early data from Coursera suggest a completion rate of 7%–9%.<ref name=KatW>{{cite web|title=MOOCs on the Move: How Coursera Is Disrupting the Traditional Classroom|url=http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=3109|work=Knowledge @ Wharton|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|accessdate=23 April 2013|format=text and video|date=7 November 2012}}</ref> Most registered students intend to explore the topic rather than complete the course, according to Koller and Ng. The completion rate for students who complete the first assignment is about 45 percent. Students paying $50 for a feature designed to prevent cheating on exams have completion rates of about 70 percent.<ref name=dropout>{{cite news|last=Kolowich|first=Steve|title=Coursera Takes a Nuanced View of MOOC Dropout Rates|url=http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/coursera-takes-a-nuanced-view-of-mooc-dropout-rates/43341|accessdate=19 April 2013|newspaper=The Chronicle of Higher Education|date=8 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

One online survey published a "top ten" list of reasons for dropping out.<ref name="Open culture 1">{{cite web|title=MOOC Interrupted: Top 10 Reasons Our Readers Didn’t Finish a Massive Open Online Course|url=http://www.openculture.com/2013/04/10_reasons_you_didnt_complete_a_mooc.html|work=Open Culture|accessdate=21 April 2013}}</ref> These were that the course required too much time, or was too difficult or too basic. Reasons related to poor course design included "lecture fatigue" from courses that were just lecture videos, lack of a proper introduction to course technology and format, clunky technology and trolling on discussion boards. Hidden costs were cited, including required readings from expensive textbooks written by the instructor that also significantly limited students' access to learning material.<ref name="in AIS Electronic Library AISeL"/> Other non-completers were "just shopping around" when they registered, or were participating for knowledge rather than a credential. |

|||

Providers are exploring multiple techniques to increase the often single-digit completion rates in many MOOCs. |

|||

===Human interaction=== |

|||

"The most important thing that helps students succeed in an online course is interpersonal interaction and support," says Shanna Smith Jaggars, assistant director of [[Columbia University]]'s [[Community College Research Center]]. Her research compared online-only and face-to-face learning in studies of community-college students and faculty in Virginia and Washington state. Among her findings: In Virginia, 32% of students failed or withdrew from for-credit online courses, compared with 19% for equivalent in-person courses.<ref name=wsj1013/> |

|||

Assigning mentors to students is another interaction-enhancing technique.<ref name=wsj1013/> In 2013 Harvard offered a popular class, ''The Ancient Greek Hero'', instructed by [[Gregory Nagy]] and taken by thousands of Harvard students over prior decades. It appealed to alumni to volunteer as online mentors and discussion group managers. About 10 former teaching fellows also volunteered. The task of the volunteers, which required 3–5 hours per week, was to focus online class discussion. The edX course registered 27,000 students.<ref name=NYT032513>{{cite news|title=Harvard Asks Graduates to Donate Time to Free Online Humanities Class By RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA Published:|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/26/education/harvard-asks-alumni-to-donate-time-to-free-online-course.html|accessdate=26 March 2013|newspaper=The New York Times|date=25 March 2013|author=Richard Perez-Pena}}</ref> |

|||

===Flipped classrooms=== |

|||

Some traditional schools blend online and offline learning, sometimes called flipped classrooms. Students watch lectures online at home and work on projects and interact with faculty while in class. Such hybrids can even improve student performance in traditional in-person classes. One fall 2012 test by San Jose State and edX found that incorporating content from an online course into a for-credit campus-based course increased pass rates to 91% from as low as 55% without the online component. "We do not recommend selecting an online-only experience over a blended learning experience," says Coursera's Ng.<ref name=wsj1013/> |

|||

===Encouragement=== |

|||

Techniques for maintaining connection with students include adding audio comments on assignments instead of writing them, participating with students in the discussion forums, asking brief questions in the middle of the lecture, updating weekly videos about the course and sending congratulatory emails on prior accomplishments to students who are slightly behind.<ref name=wsj1013/> |

|||

===Preliminaries=== |

|||

Some instructors make students begin with self-assessment surveys and videos. They asked, "What do you think it takes to be successful in online education, and do you feel that you are ready for it?" Asking those kinds of questions "improved the engagement right off the bat." |

|||

===Student fees=== |

|||

Coursera found that students who paid $30 to $90 were substantially more likely to finish the course. The fee was ostensibly for the company's identity-verification program, which confirms that they took and passed a course.<ref name=wsj1013/> |

|||

===Student scores=== |

|||

Research found that time spent on homework exercises was the largest grade predictor—more than time spent watching videos or reading. Among comparable students, one additional hour yielded a 2.2-point score increase on a 100-point scale (with a 60 required to pass). "Organizing the course around exercises and mental challenges is much more effective than around lectures", says [[Sebastian Thrun|Thrun]]. |

|||

== Industry == |

|||

MOOCs are widely seen as a major part of a larger [[disruptive innovation]] taking place in higher education.<ref name="avalanche">{{cite book|last=Barber|first=Michael|title=An Avalanche is Coming; Higher Education and the Revolution Ahead|publisher=[[Institute for Public Policy Research]] |location=London|page=71 |url=http://www.insidehighered.com/sites/default/server_files/files/FINAL%20Embargoed%20Avalanche%20Paper%20130306%20(1).pdf|authorlink=Sir Michael Barber|coauthors=Katelyn Donnelly, Saad Rizvi. Forward by [[Lawrence Summers]]|accessdate=14 March 2013|date=March 2013}}</ref><ref name="Times HE">{{cite news|last=Parr|first=Chris|title=Fund ‘pick-and-mix’ MOOC generation, ex-wonk advises|url=http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/news/fund-pick-and-mix-mooc-generation-ex-wonk-advises/2002535.article|accessdate=14 March 2013|newspaper=Times Higher Education (London)|date=14 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Watters|first=Audrey|title=Unbundling and Unmooring: Technology and the Higher Ed Tsunami|url=http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/unbundling-and-unmooring-technology-and-higher-ed-tsunami|work=Educause Review|accessdate=14 March 2013|date=5 September 2012}}</ref> In particular, the many services offered under traditional university business models are predicted to become [[unbundling|unbundled]] and sold to students individually or in newly formed bundles.<ref name=KCarey>{{cite web|last=Carey|first=Kevin|title=Into the Future With MOOC's|date=3 September 2012|url=http://chronicle.com/article/Into-the-Future-With-MOOCs/134080/|publisher=[[Chronicle of Higher Education]]|accessdate=20 March 2013}}</ref><ref name=NHarden>{{cite web|last=Harden|first=Nathan|title=The End of the University as We Know It|url=http://the-american-interest.com/article.cfm?piece=1352|publisher=The American Interest|accessdate=26 March 2013|date=January 2013}}</ref> These services include research, curriculum design, content generation (such as textbooks), teaching, assessment and certification (such as granting degrees) and student placement. MOOCs threaten existing business models by potentially selling teaching, assessment, and/or placement separately from the current package of services.<ref name="avalanche"/><ref name=Zhu>{{cite web|last=Zhu|first=Alex|title=Massive Open Online Courses – A Threat Or Opportunity To Universities?|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/sap/2012/09/06/massive-open-online-course-a-threat-or-opportunity-to-universities/|publisher=Forbes|accessdate=14 March 2013|date=6 September 2012}}</ref><ref name=Shirky>{{cite news|last=Shirky|first=Clay|title=Higher education: our MP3 is the mooc|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2012/dec/17/moocs-higher-education-transformation|accessdate=14 March 2013|newspaper=[[The Guardian]]|date=17 December 2012}}</ref> |

|||

James Mazoue, Director of Online Programs at [[Wayne State University]] describes one possible innovation: |

|||

{{Quote|The next disruptor will likely mark a tipping point: an entirely free online curriculum leading to a degree from an accredited institution. With this new business model, students might still have to pay to certify their credentials, but not for the process leading to their acquisition. If free access to a degree-granting curriculum were to occur, the business model of higher education would dramatically and irreversibly change.<ref name=Mazoue>{{cite web|last=Mazoue|first=James G.|title=The MOOC Model: Challenging Traditional Education|url=http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/mooc-model-challenging-traditional-education|publisher=EDUCAUSE Review Online|accessdate=26 March 2013|date=28 January 2013}}</ref>}} |

|||

But how universities will benefit by "giving our product away free online" is unclear.<ref name=NYT010613/> |

|||

{{quote|No one's got the model that's going to work yet. I expect all the current ventures to fail, because the expectations are too high. People think something will catch on like wildfire. But more likely, it's maybe a decade later that somebody figures out how to do it and make money.|James Grimmelmann, New York Law School professor<ref name=NYT010613>{{cite news|last=Lewin|first=Tamar|title=Students Rush to Web Classes, but Profits May Be Much Later|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/07/education/massive-open-online-courses-prove-popular-if-not-lucrative-yet.html|accessdate=6 March 2013|newspaper=[[New York Times]]|date=6 January 2013}}</ref> }} |

|||

=== Fee opportunities === |

|||

In the [[freemium]] business model the basic product – the course content – is given away free. "Charging for content would be a tragedy," said Andrew Ng. But "premium" services such as certification or placement would be charged a fee.<ref name=SA31313>{{cite journal|last=Waldrop|first=M. Mitchell|author2=Nature magazine|title=Massive Open Online Courses, aka MOOCs, Transform Higher Education and Science|journal=Scientific American|date=13 March 2013|url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=massive-open-online-courses-transform-higher-education-and-science|accessdate=28 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Course developers could charge licensing fees for educational institutions that use its materials. Introductory or "gateway" courses and some remedial courses may earn the most fees. Free introductory courses may attract new students to follow-on fee-charging classes. Blended courses supplement MOOC material with face-to-face instruction. Providers can charge employers for recruiting its students. Students may be able to pay to take a proctored exam to earn transfer credit at a degree-granting university, or for certificates of completion.<ref name=NYT010613/> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+ Overview of potential revenue sources for three MOOC providers<ref name="TechCrunch">{{cite web | title = Edukart Raises $500K To Bring Better Online Education To India And The Developing World | author= | publisher = [[TechCrunch]]| date = 2013-05-30 | url = http://techcrunch.com/2013/05/30/edukart-raises-500k-to-bring-better-online-education-to-india-and-the-developing-world/ | accessdate = 2013-09-16}}</ref><ref name="YourStory">{{cite web | title = Online education startup EduKart opens 25 franchisees to accelerate growth | author= Jubin Mehta | publisher = Your Story| date = 2013-02-13 | url = http://yourstory.in/2013/02/online-education-startup-edukart-opens-25-franchisees-to-accelerate-growth/ | accessdate = 2013-09-16}}</ref><ref name="CETIS">Yuan, Li, and Stephen Powell. MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education White Paper. University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013.http://publications.cetis.ac.uk/2013/667, p.10</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! edX |

|||

! Coursera |

|||

! UDACITY |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

* Certification |

|||

| |

|||

* Certification |

|||

* Secure assessments |

|||

* Employee recruitment |

|||

* Applicant screening |

|||

* Human tutoring or assignment marking |

|||

* Enterprises pay to run their own training courses |

|||

* Sponsorships |

|||

* Tuition fees |

|||

| |

|||

* Certification |

|||

* Employers paying to recruit talented students |

|||

* Students résumés and job match services |

|||

* Sponsored high-tech skills courses |

|||

|} |

|||

In February 2013 the [[American Council on Education]] (ACE) recommended that its members provide transfer credit from a few MOOC courses, though even the universities who deliver the courses had said that they would not.<ref name=WSJ020713>{{cite news|last=Korn|first=Melissa|title=Big MOOC Coursera Moves Closer to Academic Acceptance|url=http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324906004578288341039095024.html|accessdate=8 March 2013|newspaper=[[Wall Street Journal]]|date=7 February 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The [[University of Wisconsin]] offered multiple, [[Competency-based learning|competency-based]] [[Bachelor's degree|bachelor's]] and [[Master's degree|master's]] degrees starting Fall 2013, the first public university to do so on a system-wide basis. The university encouraged students to take online-courses such as MOOCs and complete assessment tests at the university to receive credit. ACE president Molly Corbett Broad called the UW Flexible Option program "quite visionary."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://sks.sirs.com.ezproxy.socccd.edu/cgi-bin/hst-article-display?id=SCA0984-0-1819&artno=0000348156&type=ART&shfilter=U&key=Competency+based+education&title=College+Degree%2C+No+Class+Time+Required&res=Y&ren=N&gov=Y&lnk=N&ic=N |title=Saddleback College Library |publisher=Sks.sirs.com.ezproxy.socccd.edu |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> |

|||

As of 2013 few students had applied for college credit for MOOC classes. [[Colorado State University-Global Campus]] received no applications in the year after they offered the option.<ref name="no takers">{{cite web|last=Kolowich|first=Steve|title=A University's Offer of Credit for a MOOC Gets No Takers|url=http://chronicle.com/article/A-Universitys-Offer-of-Credit/140131/|work=Chronicle of Higher Education|accessdate=25 July 2013|date=8 July 2013}} Udacity, which is offering an online master's degree in computer science in partnership with Georgia Tech, reported in October 2013 that applications for the term starting in January 2014 were more than double the number of applications that Georgia Tech receives for its traditional program. {{cite web|last=Belkin|first=douglas|title= First-of-Its-Kind Online Master’s Draws Wave of Applicants|url=http://stream.wsj.com/story/latest-headlines/SS-2-63399/SS-2-368104/|accessdate=31 October 2013|date=30 October 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Academic Partnerships is a company that helps public universities move their courses online. According to its chairman, Randy Best "We started it, frankly, as a campaign to grow enrollment. But 72 to 84 percent of those who did the first course came back and paid to take the second course."<ref name=NYT012313>Tamar Lewin. [http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/23/education/public-universities-to-offer-free-online-classes-for-credit.html Public Universities to Offer Free Online Classes for Credit]. 23 January 2013</ref> |

|||

While Coursera takes a larger cut of any revenue generated – but requires no minimum payment – the not-for-profit EdX has a minimum required payment from course providers, but takes a smaller cut of any revenues, tied to the amount of support required for each course.<ref>{{cite web|last=Kolowich |first=Steve |url=http://chronicle.com/article/How-EdX-Plans-to-Earn-and/137433/ |title=How EdX Plans to Earn, and Share, Revenue From Free Online Courses - Technology - The Chronicle of Higher Education |publisher=Chronicle.com |date=2013-02-21 |accessdate=2013-05-30}}</ref> |

|||

=== Industry structure === |

|||

The industry has an unusual structure, consisting of linked groups including MOOC providers, the larger non-profit sector, universities, related companies and [[venture capitalist]]s. ''[[The Chronicle of Higher Education]]'' lists the major providers as the non-profits [[Khan Academy]] and [[edX]], and the for-profits [[Udacity]] and [[Coursera]].<ref name="Major players">{{cite web|title=Major Players in the MOOC Universe|url=http://chronicle.com/article/The-Major-Players-in-the-MOOC/138817/#id=overview|work=Chronicle of Higher Education|accessdate=29 April 2013|date=29 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The larger non-profit organizations include the [[Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation]], the [[MacArthur Foundation]], the [[National Science Foundation]], and the [[American Council on Education]]. University pioneers include [[Stanford]], [[Harvard]], [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology|MIT]], the [[University of Pennsylvania]], [[California Institute of Technology|CalTech]], the [[University of Texas at Austin]], the [[University of California at Berkeley]], [[San Jose State University]]<ref name="Major players"/> and the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay [[IIT Bombay]]. |

|||

Related companies include [[Google]] and educational publisher [[Pearson PLC]]. Venture capitalists include [[Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers]], [[New Enterprise Associates]] and [[Andreessen Horowitz]].<ref name="Major players"/> |

|||

The changes predicted from MOOCs generated objections in some quarters. The San Jose State University philosophy faculty wrote in an open letter to Harvard University professor and MOOC teacher [[Michael Sandel]]: |

|||

{{Quote|Should one-size-fits-all vendor-designed blended courses become the norm, we fear two classes of universities will be created: one, well-funded colleges and universities in which privileged students get their own real professor; the other, financially stressed private and public universities in which students watch a bunch of video-taped lectures.<ref name="Dear Sandel">{{cite news|title=San Jose State to Michael Sandel: Keep your MOOC off our campus|url=http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/brainiac/2013/05/san_jose_state.html|accessdate=7 May 2013|newspaper=[[Boston Globe]]|date=3 May 2013}}</ref> }} |

|||

== Technology == |

|||

Unlike traditional courses, MOOCs require additional skills, provided by videographers, instructional designers, IT specialists and platform specialists. [[Georgia Institute of Technology|Georgia Tech]] professor Karen Head reports that 19 people work on their MOOCs and that more are needed.<ref name=GTech>{{cite news|last=Head|first=Karen|title=Sweating the Details of a MOOC in Progress|url=http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/sweating-the-details-of-a-mooc-in-progress/43315|accessdate=6 April 2013|newspaper=[[Chronicle of Higher Education]]|date=3 April 2013}}</ref> The platforms have availability requirements similar to media/content sharing websites, due to the large number of enrollees. MOOCs typically use [[cloud computing]]. |

|||

Course delivery involves asynchronous access to videos and other learning material, exams and other assessment, as well as online forums. Before 2013 each MOOC tended to develop its own delivery platform. EdX in April 2013 joined with Stanford University, which previously had its own platform called Class2Go, to work on [[XBlock]] SDK, a joint open-source platform. It is available to the public under the [[Affero GPL]] open source license, which requires that all improvements to the platform be publicly posted and made available under the same license.<ref name=edXPressRelease>{{cite web|title=edX Takes First Step toward Open Source Vision by Releasing XBlock SDK |url=https://www.edx.org/press/edx-takes-first-step-toward-open-source|work=www.edx.org|publisher=edX|accessdate=6 April 2013}}{{dead link|date=July 2013}}</ref> Stanford Vice Provost John Mitchell said that the goal was to provide the "[[Linux]] of online learning."<ref name="Open Source">{{cite news|last=Young|first=Jeffrey R.|title=Stanford U. and edX Will Jointly Build Open-Source Software to Deliver MOOCs|url=http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/stanford-u-and-edx-will-jointly-build-open-source-software-to-deliver-moocs/43301|accessdate=3 April 2013|newspaper=[[Chronicle of Higher Education]]|date=5 April 2013}}</ref> This is unlike companies such as Coursera that have developed their own platform.<ref name="courserastack">{{cite web|title=What is Coursera's Stack?|url=http://www.quora.com/Coursera/What-is-Courseras-stack|work=www.quora.org|publisher=Qoura|accessdate=8 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

== Potential benefits == |

|||

The MOOC Guide<ref name="MoocGuide">{{cite web | url=http://moocguide.wikispaces.com/2.+Benefits+and+challenges+of+a+MOOC | title=Benefits and Challenges of a MOOC | publisher=MoocGuide | date=7 Jul 2011<!-- 11:27 pm -->| accessdate=4 February 2013}}</ref> lists 12 benefits: |

|||

# Appropriate for any setting that has connectivity (Web or Wi-Fi) |

|||

# Any language or multiple languages |

|||

# Any online tools |

|||

# Escape time zones and physical boundaries |

|||

# Produce and deliver in short timeframe (e.g. for relief aid) |

|||

# Contextualized content can be shared by all |

|||

# Informal setting |

|||

# Peer-to-peer contact can trigger serendipitous learning |

|||

# Easier to cross disciplines and institutional barriers |

|||

# Lower barriers to student entry |

|||

# Enhance personal learning environment and/or network by participating |

|||

# Improve lifelong learning skills |

|||

== Experience and feedback == |

|||

About 10% of the students who sign up typically complete the course.<ref name="NYTimes030613"/> Most participants participate peripherally ("lurk"). For example, one of the first MOOCs in 2008 had 2200 registered members, of whom 150 actively interacted at various times.<ref>Mackness, Jenny, Mak, Sui Fai John, and Williams, Roy [http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fss/organisations/netlc/past/nlc2010/abstracts/PDFs/Mackness.pdf "The Ideals and Reality of Participating in a MOOC"], Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networked Learning 2010</ref> |

|||

Learners control where, what, how and with whom they learn, although different learners choose to exercise more or less of that control.<ref name="oltraining6">Kop, Rita, and Fournier, Helene [http://www.oltraining.com/SDLwebsite/IJSDL/IJSDL7.2-2010.pdf#page=6 "New Dimensions to Self-Directed Learning in an Open Networked Learning Environment"]{{dead link|date=July 2013}}, ''International Journal of Self-Directed Learning'', Volume 7, Number 2, Fall 2010</ref> |

|||

Students include traditional university students, along with degreed professionals, educators, business people, researchers and others interested in internet culture.<ref name=KatW/> |

|||

Principles of [[openness]] inform the creation, structure and operation of MOOCs. The extent to which practices of Open Design in educational technology<ref>{{cite book|last1=Iiyoshi |first1=Toru |last2=Kumar |first2=M. S. Vijay |title=Opening Up Education: The Collective Advancement of Education through Open Technology, Open Content, and Open Knowledge |publisher=MIT Press |year=2008 |ISBN=0262033712}}</ref> are applied vary. Research by Kop and Fournier<ref name="oltraining6"/> highlighted as major challenges the lack of social presence and the high level of autonomy required. |

|||

{|class=wikitable align=right |

|||

|+Attributes of major MOOC providers<ref>Yuan, Li, and Stephen Powell. MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education White Paper. University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013. http://publications.cetis.ac.uk/2013/667.</ref> |

|||

! Initiatives !! For profit !! Free to access !! Certification fee !! Institutional credits |

|||

|- |

|||

! EdX |

|||

| {{no}} || {{yes}} || {{yes}} || {{no}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Coursera |

|||

| {{yes}} || {{yes}} || {{yes}} || {{partial}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Udacity |

|||

| {{yes}} || {{yes}} || {{yes}} || {{partial}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Udemy |

|||

| {{yes}} || {{partial}} || {{yes}} || {{partial}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! P2PU |

|||

| {{no}} || {{yes}} || {{no}} || {{no}} |

|||

|} |

|||

Grading by peer review has had mixed results. In one example, three fellow students grade one assignment for each assignment that they submit. The grading key or rubric tends to focus the grading, but discourages more creative writing.<ref name="BG Haber"/> |

|||

[[A. J. Jacobs]] in an op-ed in the ''[[New York Times]]'' graded his experience in 11 MOOC classes overall as a "B".<ref name=AJJ>{{cite news|last=Jacobs|first=A.J.|title=Two Cheers for Web U!|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/21/opinion/sunday/grading-the-mooc-university.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0|accessdate=23 April 2013|newspaper=New York Times, Sunday Review|date=21 April 2013}}</ref> He rated his professors as '"B+", despite "a couple of clunkers", even comparing them to pop stars and "A-list celebrity professors." Nevertheless he rated teacher-to-student interaction as a "D" since he had almost no contact with the professors. The highest rated ("A") aspect of Jacobs' experience was the ability to watch videos at any time. Student-to-student interaction and assignments both received "B-". Study groups that didn't meet, [[Troll (Internet)|trolls]] on message boards and the relative slowness of online vs. personal conversations lowered that rating. Assignments included multiple choice quizzes and exams as well as essays and projects. He found the multiple choice tests stressful and peer graded essays painful. He completed only 2 of the 11 classes.<ref name=AJJ/><ref name="NPR AJ">{{cite web|title=Making the most of MOOCs: the ins and outs of e-learning|url=http://www.npr.org/player/v2/mediaPlayer.html?action=1&t=1&islist=false&id=178623872&m=178623848|work=Talk of the Nation|publisher=National Public Radio|accessdate=23 April 2013|format=Radio interview and call-in|date=23 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

=== Humanities vs science === |

|||

Many popular MOOC sites were created by scientists. However, MOOCs are also useful for teaching poetry. "There was a real question of whether this would work for humanities and social science," says Ng. However, psychology and philosophy courses are among Coursera's most popular. Student feedback and completion rates suggest that they are as successful as math and science courses.<ref name=wsj1013/> |

|||

In the community-college study, Ms. Jaggars found lower online grades in English than in natural-science classes, although no definitive explanations emerged.<ref name=wsj1013/> |

|||

=== Students served === |

|||

By June 2012 more than 1.5 million people had registered for classes through Coursera, Udacity and/or edX.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/06/11/experts-speculate-possible-business-models-mooc-providers |title=Experts speculate on possible business models for MOOC providers |author=Steve Kolowich |publisher=Inside Higher Ed |date=2012-06-11| accessdate=2013-10-04}}</ref><ref>See, e.g. the first 3 minutes of the video {{cite web|title=Daphne Koller: What we're learning from online education|url={{TED|talks/daphne_koller_what_we_re_learning_from_online_education.html}}|publisher=TED|accessdate=23 April 2013|date=June 2012}}</ref> As of 2013, the range of students registered appears to be broad, diverse and non-traditional, but concentrated among English-speakers in rich countries. By March 2013, Coursera alone had registered about 2.8 million learners.<ref name="SA31313"/> |

|||

{|class="wikitable" align=right |

|||

|+Coursera enrollees |

|||

! Country!! Percentage |

|||

|- |

|||

| United States || 27.7% |

|||

|- |

|||

| India || 8.8% |

|||

|- |

|||

| Brazil || 5.1% |

|||

|- |

|||

| United Kingdom || 4.4% |

|||

|- |

|||

| Spain || 4.0% |

|||

|- |

|||

| Canada || 3.6% |

|||

|- |

|||

| Australia || 2.3% |

|||

|- |

|||

| Russia || 2.2% |

|||

|- |

|||

| Rest of world || 41.9% |

|||

|} |

|||

By October 2013, Coursera enrollment continued to surge, surpassing 5 million, while edX had independently reached 1.3 million.<ref name=wsj1013>{{cite web|last=Fowler |first=Geoffrey A. |url=http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303759604579093400834738972.html |title=An early report card on MOOCs |work=Wall Street Journal |date=2013-10-08 |accessdate=2013-10-14}}</ref> |

|||

A course billed as "Asia's first MOOC" given by the [[Hong Kong University of Science and Technology]] through Coursera starting in April 2013 registered 17,000 students. About 60% were from "rich countries" with many of the rest from middle-income countries in Asia, South Africa, Brazil or Mexico. Fewer students enrolled from areas with more limited access to the internet, and students from the People's Republic of China may have been discouraged by Chinese government policies.<ref name="HK MOOC">{{cite web|last=Sharma|first=Yojana|title=Hong Kong MOOC Draws Students from Around the World|url=http://chronicle.com/article/Hong-Kong-MOOC-Draws-Students/138723/|work=Chronicle of Higher Education|accessdate=23 April 2013|date=22 April 2013}} reprinted from ''University World News''</ref> |

|||

"We have the whole gamut of older and younger, experienced and less experienced students, and also academics and probably some people who are experts in related fields," according to Naubahar Sharif who teaches the class on ''Science, Technology and Society in China.'' "We do have students from China as well, in places where Internet connections are more reliable."<ref name="HK MOOC"/> |

|||

Koller stated in May 2013 that a majority of the people taking Coursera courses had already earned college degrees.<ref>Steve Kolowich, [http://chronicle.com/article/In-Deals-With-10-Public/139533/?cid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en "In Deals With 10 Public Universities, Coursera Bids for Role in Credit Courses," ''Chronicle of Higher Education'' 30 May 2013]</ref> |

|||

According to a Stanford University study of a more general group of students "active learners" – anybody who participated beyond just registering – found that 64% of high school active learners were male and 88% were male for undergraduate- and graduate-level courses.<ref name="lytics"/> |

|||

In 2013, the [[Chronicle of Higher Education]] surveyed 103 professors who had taught MOOCs. "Typically a professor spent over 100 hours on his MOOC before it even started, by recording online lecture videos and doing other preparation," though some instructors' pre-class preparation was "a few dozen hours." The professors then spent 8–10 hours per week on the course, including participation in discussion forums.<ref name="Chron survey"/> |

|||

The medians were: 33,000 students enrollees; 2,600 passing; and 1 teaching assistant helping with the class. 74% of the classes used automated grading, and 34% used peer grading. 97% of the instructors used original videos, 75% used open educational resources and 27% used other resources. 9% of the classes required a physical textbook and 5% required an e-book.<ref name="Chron survey">{{cite news|last=Kolowich|first=Steven|title=The Professors Who Make the MOOCs|url=http://chronicle.com/article/The-Professors-Behind-the-MOOC/137905/#id=overview|accessdate=26 March 2013|newspaper=[[Chronicle of Higher Education]]|date=26 March 2013}}</ref><ref name="additional results">{{cite news|title=Additional Results From The Chronicle's Survey|url=http://chronicle.com/article/The-Professors-Behind-the-MOOC/137905/#id=results|accessdate=26 March 2013|newspaper=[[Chronicle of Higher Education]]|date=26 March 2013}}</ref> |

|||

=== Student demographics === |

|||

A study from Stanford University's Learning Analytics group identified four types of students: auditors, who watched video throughout the course, but took few quizzes or exams; completers, who viewed most lectures and took part in most assessments; disengaged learners, who quickly dropped the course; and sampling learners, who might only occasionally watch lectures.<ref name="lytics">{{cite web|last=MacKay|first=R.F.|title=Learning analytics at Stanford takes huge leap forward with MOOCs|url=http://news.stanford.edu/news/2013/april/online-learning-analytics-041113.html|work=Stanford Report|publisher=Stanford University|accessdate=22 April 2013|date=11 April 2013}}</ref> They identified the following percentages in each group:<ref name="Decon Diseng">{{cite web|title=Deconstructing Disengagement: Analyzing Learner Subpopulations in Massive Open Online Courses|url=http://www.stanford.edu/~cpiech/bio/papers/deconstructingDisengagement.pdf|work=LAK conference presentation|accessdate=22 April 2013|author=René F. Kizilcec|author2=Chris Piech |author3=Emily Schneider }}</ref> |

|||

{|class="wikitable unsortable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Course |

|||

! Auditing |

|||

! Completing |

|||

! Disengaging |

|||

! Sampling |

|||

|- |

|||

! High school |

|||

| 6% |

|||

| 27% |

|||

| 28% |

|||

| 39% |

|||

|- |

|||

! Undergraduate |

|||

| 6% |

|||

| 8% |

|||

| 12% |

|||

| 74% |

|||

|- |

|||

! Graduate |

|||

| 9% |

|||

| 5% |

|||

| 6% |

|||

| 80% |

|||

|} |

|||

Jonathan Haber focused on questions of what students are learning and student demographics. About half the students taking US courses are from other countries and do not speak English as their first language. He found some courses to be meaningful, especially about reading comprehension. Video lectures followed by multiple choice questions can be challenging since they are often the "right questions." Smaller discussion boards paradoxically offer the best conversations. Larger discussions can be "really, really thoughtful and really, really misguided," with long discussions becoming rehashes or "the same old stale left/right debate."<ref name="BG Haber">{{cite news|last=Bombardieri|first=Marcella|title=Can you MOOC your way through college in one year?|url=http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/04/13/can-you-mooc-your-way-through-college-one-year-can-you-mooc-your-way-through-college-one-year/lAPwwe2OYNLbP9EHitgc3L/story.html|accessdate=23 April 2013|newspaper=Boston Globe|date=14 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

== Challenges and criticisms == |

|||

The MOOC Guide<ref name="MoocGuide" /> lists 5 possible challenges for collaborative-style MOOCs: |

|||

# Participants must create their own content |

|||

# [[Digital literacy]] is necessary |

|||

# Time and effort required from participants<!-- seriously? --> |

|||

# It is organic, which means the course will take on its own trajectory (you have got to let go).<!-- what can this possibly mean? --> |

|||

# Participants must self-regulate and set their own goals |

|||

Other concerns include: |

|||

The 'territorial' nature of MOOCs<ref name="TerritorialDimensions">{{cite web | url=http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/globalhighered/territorial-dimensions-moocs | title=On the territorial dimensions of MOOCs | publisher=Inside Higher Ed | date=3 December 2012 | accessdate=4 February 2013 | author=Olds, Kris}}</ref> with little discussion around: 1) who enrolls in/completes courses; 2) The implications of courses scaling across country borders, and potential difficulties with relevance and knowledge transfer; 3) the need for territory-specific study of locally relevant issues and needs. |

|||

Other features associated with early MOOCs, such as open licensing of content, open structure and learning goals, community-centeredness, etc., may not be present in all MOOC projects.<ref name="MOOC Misnomer"/> |

|||

Effects on the structure of higher education were lamented for example by [[Moshe Y. Vardi]], who finds an "absence of serious pedagogy in MOOCs", indeed in all of higher education. He criticized the format of "short, unsophisticated video chunks, interleaved with online quizzes, and accompanied by social networking."{{clarify|reason=Reads like a description rather than a critique.|date=October 2013}} An underlying reason is simple cost cutting pressures, which could hamstring the higher education industry.<ref name=Vardi>{{cite journal|last=Vardi|first=Moshe Y.|title=Will MOOCs destroy academia?|journal=Communications of the ACM|date=November 2012|volume=55|issue=11|page=5|url=http://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2012/11/156587-will-moocs-destroy-academia/fulltext|accessdate=23 April 2013|doi=10.1145/2366316.2366317}}</ref> |

|||

[[Cary Nelson]], former president of the [[American Association of University Professors]] claimed that MOOCs are not a reliable means of supplying credentials, stating that "It’s fine to put lectures online, but this plan only degrades degree programs if it plans to substitute for them." Sandra Schroeder, chair of the Higher Education Program and Policy Council for the [[American Federation of Teachers]] expressed concern that "These students are not likely to succeed without the structure of a strong and sequenced academic program."<ref>{{cite web|last=Basu |first=Kaustuv |url=http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/05/23/faculty-groups-consider-how-respond-moocs |title=Faculty groups consider how to respond to MOOCs |publisher=Inside Higher Ed |date=2012-05-23 |accessdate=2013-10-13}}</ref> |

|||

With a 60% majority, the [[Amherst College]] faculty rejected the opportunity to work with edX based on a perceived incompatibility with their seminar-style classes and personalized feedback. Some were concerned about issues such as the "information dispensing" teaching model of lectures followed by exams, the use of multiple-choice exams and peer-grading. The [[Duke University]] faculty took a similar stance in the spring of 2013. The effect of MOOCs on second- and third-tier institutions and of creating a professorial "star system" were among other concerns.<ref name="IHE 1">{{cite web|last=Rivard|first=Ry|title=EdX Rejected|url=http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/04/19/despite-courtship-amherst-decides-shy-away-star-mooc-provider|publisher=Inside Higher Education|accessdate=22 April 2013|date=19 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

In April 2013, the Philosophy Department faculty of San Jose State University wrote an open letter to Harvard Professor Michael Sandel outlining their concerns about MOOCs, most notably their "fear that two classes of universities will be created: one, well- funded colleges and universities in which privileged students get their own real professor; the other, financially stressed private and public universities in which students watch a bunch of video-taped lectures and interact, if indeed any interaction is available on their home campuses, with a professor that this model of education has turned into a glorified teaching assistant." The letter was published in The Chronicle of Higher Education.<ref>http://chronicle.com/article/The-Document-Open-Letter-From/138937/</ref> |

|||