Մասնակից:WildAndWhite/Ավազարկղ

Աֆրիկյան պատմություններ և գրառումներ

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Եգիպտոս

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

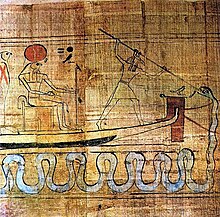

Հին Եգիպտոսի դիցաբանությունում Ապեպը կամ Ապոպիսը հսկա օձակերպ արարած է, որն ապրում է Դուատ՝ Եգիպտական անդրաշխարհում[1][2]։ Մոտ Ք․ա․ 310 թվականին գրված Bremner-Rhind պապիրուսն իր մեջ ներառում է ավելի հին եգիպտական ավանդույթի մասին տեղեկատվություն, արևի մայրամուտը պայմանավորված է նրանով, որ Ռա իջնում է դեպի Դուատ՝ Ապեպի դեմ պայքարելու համար[1][2]։ Որոշ աղբյուրների համաձայն՝ Ապեպն ունի կայծքարային ապարներից կազմված գլուխներով ութ տղամարդու հասակ[2]։ Thunderstorms and earthquakes were thought to be caused by Apep's roar[2] and solar eclipses were thought to be the result of Apep attacking Ra during the daytime.[2] In some myths, Apep is slain by the god Set.[2] Nehebkau is another giant serpent who guards the Duat and aided Ra in his battle against Apep.[2] Nehebkau was so massive in some stories that the entire earth was believed to rest atop his coils.[2] Denwen is a giant serpent mentioned in the Pyramid Texts whose body was made of fire and who ignited a conflagration that nearly destroyed all the gods of the Egyptian pantheon.[2] He was ultimately defeated by the Pharaoh, a victory which affirmed the Pharaoh's divine right to rule.[2]

The ouroboros was a well-known Egyptian symbol of a serpent swallowing its own tail.[3] The precursor to the ouroboros was the "Many-Faced",[3] a serpent with five heads, who, according to the Amduat, the oldest surviving Book of the Afterlife, was said to coil around the corpse of the sun god Ra protectively.[3] The earliest surviving depiction of a "true" ouroboros comes from the gilded shrines in the tomb of Tutankhamun.[3] In the early centuries AD, the ouroboros was adopted as a symbol by Gnostic Christians[3] and chapter 136 of the Pistis Sophia, an early Gnostic text, describes "a great dragon whose tail is in its mouth".[3] In medieval alchemy, the ouroboros became a typical western dragon with wings, legs, and a tail.[3] A famous image of the dragon gnawing on its tail from the eleventh-century Codex Marcianus was copied in numerous works on alchemy.[3]