Մասնակից:Emptyfear/Էվոլյուցիա

Մուտացիա

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Մուտացիաները բջջի գենոմի ԴՆԹ-ի փոփոխություններն են։ Մուտացիաները կարող են փոփոխել գենի պրոդուկտ, սահմանափակել գենի ֆունկցիան կամ չունենալ որևէ ազդեցություն։ Դրոզոֆիլ պտղաճանճի վրա իրականացվախ հետազոտությունների համաձայն՝ եթե մուտացիան կարողանում է փոփոխել գենի պրոդուկտը, ապա 70%-ով այն կարող է վնասակար լինել, իսկ մնացածը սովորաբար չեզոք ազդեցություն է, քան՝ օգտակար[1]։

Մուտացիաները ներառում են նաև քրոմոսոմի որոշակի տեղամասի դուպլիացիան (սովորաբար գենետիկական ռեկոմբինացիան), որի արդյունքում գենոմում կարող են առաջանալ գենի լրացուցիչ կրկնօրինակներ[2]։ Գեների լրացուցիչ կրկնօրինակները նոր գեների էվոլյուցիայի համար կարևոր նյութ են[3]։ Սա կարևոր է, քանի որ գեների մեծ մասը էվոլուցվում են գեների ընտանիքների ներսում՝ արդեն գոյություն ունեցող նախագեների վրա, որոնք ունեն նույն նախնին[4]։ Օրինակ՝ մարդու աչքի գեները ապահովում են այն կառույցները, որոնք ընկալում են լույսը՝ երեք գեն գունային տեսողության և մեկ գեն՝ գիշերային տեսողության համար։ Այս բոլոր չորս գեները ծագել են մեկ ընդհանուր նախնի գենից[5]։

Նոր գեները ծագում են նախնի գենից, երբ նախնի գենի կրկնօրինակը մուտացվում է և ձեռք բերում նոր ֆունկցիա։ Այս գործընթացը ավելի հեշտանում է, երբ տվյալ գենը ունի կրկնօրինակ, քանի որ կրկնօրինակի առկայությունը մեծացնում է համակարգի առատությունը․ նույն գենի երկու կրկնօրինակներից մեկը կարող է շարունակել իր ֆունկցիան, այն դեպքում, երբ մյուսը կարող է էվոլուցվել՝ ձեռք բերելով նոր ֆունկցիա[6][7]։ Մյուս տեսակի մուտացիաները կարող են ձևավորել ընդհանրապես նոր գեներ՝ նախկինում չկոդավորող ԴՆԹ-ից[8][9]։

Նոր գեների սերունդը կարող է ներառել որոշ թվով այնպիսի գեներ, որոնք դուպլիկացված են, որոնք հետագայում ռեկոմբինացվում են՝ ձևավորելով նոր ֆունկցիաներ[10][11]։ Երբ նոր գեներնբ առաջանում են արդեն գոյություն ունեցող հատվածներից, դոմենները գործում են որպես պարզ անկախ միավորներ, որոնք կարող են խառնվել՝ առաջացնելով նոր վերադասավորումներ նոր կամ ավելի բարդ ֆունկցիաներով[12]։ Օրինակ՝ պոլիկետիդ սինթետազը մեծ ֆերմենտներ են, որոնք ստեղծում են հակաբիոտիկներ։ Այն պարունակում է շուրջ հարյուր անկախ դոմեններ, որոնցից յուրաքանչյուրը շղթայաբար կատալիզում է ընդհանուր գործընթացի մի մասը[13]։

Սեռ և ռեկոմբինացիա

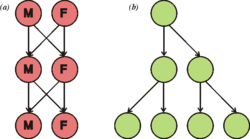

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Ասեքսուալ օրգանիզմների մոտ գեները ժառանգվում են միասնաբար կամ շղթայակցված և չեն վերարտադրման ժամանակ չեն խառնվում այլ օրգանիզմների գեների հետ։ Հակառակ դրան՝ սեռական բազմացող օրգանիզմների սերունդները պարունակում են իրենց ծնողների քրոմոսոմների պատահական խառնուրդներ, որոնք բաշխվում են անկախ բաշխման միջոցով։ Սեռական օրգանիզմների մոտ հանդիպում է հոմոլոգ ռեկոմբինացիան, որի ժամանակ երկու հոմոլոգ քրոմոսոմներ փոխանակում են ԴՆԹ-ի հատվածներ[14]։ Ռեկոմբինացիան և ռեասորտիմենտը չեն փոխում ալելների հաճախականությունները, բայց փոխում են ալելների կապերը՝ ձևավորելով ալելների նոր կոմբինացիաներ[15]։ Սեռական բազամցումը մեծանում է գենետիկական փոփոխականությունը և կարող է արագացնել էվոլյուցիայի ընթացքը.[16][17]։

Ջոն Մայնարդ Սմիթը նկարագրել է սեռի երկու արժեքները[18]։ Առաջինն այն է, որ սեռական դիմորֆիզմ ունեցող տեսակների մոտ, սեռերից միայն մեկը կարող է տանել երիտասարդներին, սա չի վերաբերում հերմաֆրոդիտ տեսակներին՝ բույսերի մեծամասնությանն ու որոշ անողնաշարավորներին։ Երկրորդն այն է, որ սեռական բազմացող անհատների մոտ գեներում պահպանվող գենետիկական նյութի միայն կեսն է անցնում սերունդներին, որը սերնդեսերունդ ավելի է պակասու[19]մ։ Սեռական բազմացումը էուկարիոտների բազմաբջիջ օրգանիզմների մոտ ավելի տարածված է։ Կարմիր թագուհու վարկածը փորձում է բացատրել սեռական բազմացման նշանակությունը որպես այլ տեսակների հետ փոփոխվող պայմաններում շարունակական էվոլյուցիայի և հարմարման հնարավորություն նպաստող երույթ

Գեների հոսք

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Գեների հոսքը պոպուլյացիայի միջև և տեսակների միջև գեների փոխանակությունն է[20]։ Այն պոպուլյացիաների և տեսակների համար կարող է լինել փոփոխականության աղբյուր։ Գեների հոսքը կարող է պայմանավորված լինել պոպուլյացիաներից անհատների շարժմամբ, ինչպես նաև տեսակի աշխարհագրական կամ միջավայրային տեղաշարժմամբ։

Գեների փոխանակումը տեսակների միջև ներառում է հիբրիդ օրգանիզմների առաջացումը և գեների հորիզոնական տեղափոխումը։ Գեների հորիզոնական տեղափոխումը միմյանց սերունդ չհանդիսացող տեսակների միջև գենետիկական նյութի փոխանակումն է, որը սովորաբար հանդիպում է բակտերիաների մոտ[21]։ Բժշկության մեջ սա օգնում է օրինակ հակաբիոտիկների հանդեպ կայունության տարածմանը, երբ բակտերիաներից մեկը ձեռք է բերում հակաբիոտիկների հանդեպ կայունություն, այն շատ արագ տարածվում է մյուս տեսակների մեջ[22]։ Էուկարիոտների և բակտերիաների մոտ նույնպես հայտնաբերվել է գեների հորիզոնական տեղափոխություն[23][24]։ Մեծածավալ գեների հորիզոնական տեղափոխության օրինակ է Bdelloidea ռոտիֆերները, որոնք գեներ են ստացել բակտերիաներից, սնկերից և բույսերից[25]։ Վիրուսները նույնպես կարող են գեներ տեղափոխել մեկ օրգանիզմից մյուսը՝ թույլ տալով գեների փոխանակման իրականացումը անգամ կենսաբանության տարբեր դոմենների միջև[26]։

Հնարավոր է, որ մեծածավալ գեների փոխանակում տեղի է ունեցել էուկարիոտ բջիջներների նախնիների և բակտերիաների միջև՝ քլորոպլաստների և միտքոնդրիումների ձեռքբերման ժամանակ։ Հնարավոր է, որ էուկարիոտները ծագել են բակտերիաների և արքեաների միջև գեների փոխանակման արդյունքում[27]։

Մեխանիզմներ

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Նեոդարվինյան տեսանկյունից էվոլյուցիան ընթանում է, երբ պոպուլյացիայի ներսում ազատ խաչասերման պայմաններում տեղի են ունենում ալելների հաճախականությունների փոփոխություններ։ Օրինակ՝ գիշերային թիթեռների պոպուլյացիայում սև գույնի ալելը հետզհետե դառնում է դոմինանտ[28]։ Ալելի հաճախականության վրա կարող են ազդել բնական ընտրությունը, գեների դրեյֆը, գեների հիչհայքինգը, մուտացիան և գեների հոսքը։

Բնական ընտրություն

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Բնական ընտրության միջոցով տեղի ունեցող բնական ընտրությունը գործընթաց է, որի ժամանակ այն հատկանիշները, որոնք բարձրացնում են բազմացման և գոյատևման արդյունավերտությունը պոպուլյացիայում սերնդեսերունդ դառնում են ավելի տարածված։ Բնական ընտրությունը կարելի է ապացուցել երեք պարզ փաստերով՝

- պոպուլյացիայում օրգանիզմները միմյանցից տարբերվում են ձևաբանական, ֆիզիոլոգիական և վարքային հատկանիշներով (ֆենոտիպային փոփոխականություն),

- տարբեր հատկանիշներ ապահովում են գոյատևման և վերարտադրման տարբեր հաճախականություն (տարբերակող հարմարողականություն),

- հատկանիշները կարող են ժառանգվել մի սերնդից մյուսը (հարմարողականության ժառանգում[29]։

Սերունդները ստեղծվում են միշտ ավելի շատ, քան կարող են գոյատևել, որի պատճարով պայմանները ստեղծում են մրցակցություն տարբեր օրգանիզմների միջև, որոնք պայքարում են բազմացման և գոյատևման համար։ Սրա հետևանքով այն օրգանիզմները, որոնք ունեն մրցակցության մեջ առավելություն տվող հատկանիշներ ավելի հավանական է, որ կփոխանցվեն հաջորդ սերունդներին[30]։

Բնական ընտրության կենտրոնական գաղափարը օրգանիզմի էվոլյուցիոն հարմարողականությունն է[31]։ Հարմարողականությունը չափվում է օրգանիզմի՝ գոյատևելու և բազմանալու ընդունակությամբ, որը որոշում է հաջորդ սերնդում կատարված գենետիկական ներդրումը[31]։ Հարմարողականությունը, սակայն, չի նկարագրվում սերունդների ընդհանուր թվով, այլ հաջորդող սերունդների այն հարաբերությամբ, որոնք պարունակում են ծնողական ձևի գեները։ Օրինակ՝ օրգանիզմը կարող է գոյատևել և բազմանալ շատ արագ, բայց սերունդները լինեն թույլ և փոքր գոյատևելու համար․ այդ դեպքում օրգանիզմը շատ քիչ գենետիկական ներդրում կունենա հաջորդ սերունդներում և հետևաբար կունենա ցածր հարամարողականություն[31]։

Եթե տվյալ ալելն ավելի է բարձրացնում հարմարողականությունը գենի մյուս ալելների նկատմամբ, այն ամեն նոր սերնդում հետզհետե կդառնա ավելի ու ավելի տարածված։ Ասում են, որ այսպիսի հատկանիշները ընտրության են ենթարկվել[32]։ Ալելի հարմարողականությունը կայուն հատկանիշ չէ․ շրջակա միջավայրի փոփոխության դեպքում, նախկին չեզոք կամ վնասակար հատկանիշները կարող են վերածվել օգտակարի և հակառակը՝ նախկինում օգտակար հատկանիշները՝ դառնալ վնասակար[33]։ Այնուամենայնիվ, այն հատկանիշները, որոնք անցյալում բնական ընտրության ճանապարհով անհետացել են, չեն կարող վերաէվոլուցվել և հայտնվել նույնական տեսքով (Դոլլոյի օրենք)[34][35]:

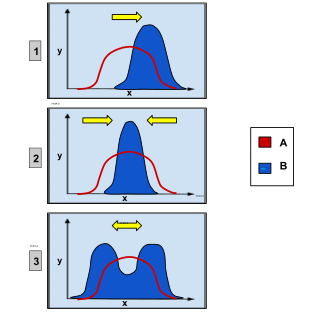

Պոպուլյացիայի ներսում բնական ընտրությունը կարող է լինել երեք տեսակի այն հատկանիշների համար, որոնք կարող են ստանալ տարբեր հատկանիշներ, օրինակ՝ հասակը։ Առաջինը շարժական ընտրությունն է, որը ժամանակի ընթացքում փոփոխում է հատկանիշի միջին արժեքը, օրինակ՝ օրգանիզմները դանդաղորեն ավելի բարձրահասակ են դառնում[36]։ Հաջորդը՝ կործանիչ ընտրությունը հատկանիշի ծայրահեղ արժեքներին ուղղված ընտրությունն է , որի արդյունքում սովորաբար առաջանում են երկու տարբեր հատկանիշներ։ Այս դեպքում առավելություն ունեն կարճահասակ կամ բարձրահասակ տեսակները, բայց ոչ միջին հասակ ունեցողները։ Եվ վերջինը՝ կայունացնող ընտրությունը բերում է ծայրահեղ արժեքների նվազմանը, որի ադյունքում պահպանվում է միայն միջին արժեքը, նվազում է բազմազանությունը[30][37]։

Բնական ընտրության հատուկ տեսակ է սեռական ընտրությունը, որը ուղղված է այնպիսի հատկանիշների ուղղությամբ, որոնք մեծացնում են խաչասերվելու հավանականությունը՝ մեծանցելով օրգանիզմի գրավչությունը հնարավոր զույգի համար[38]։ Սեռական ընտրության հետևռանքով առաջացած հատկանիշները կենդանիների մեծ մասի մոտ ավելի աչքի են ընկնում արուների մոտ։ Չնայած սեռական առումով առավելությանը, մեծ չափերը, բարձր կանչերը և վառ գունավորումը հաճախ է գրավում գիշատիչներին[39][40]։

Սեռական այս հատկանիշների գոյատևման համար անբարենտպաստ լինելը կարգավորում է բարձր արդյունավետությամբ բազմացող արուների քանակը[41]։

Բնական ընտրությունը բնությունը դարձնում է որոշիչ՝ առանձնյակների այս կամ այն հատկանիշների գոյատևման համար։ «Բնություն» ասելով այս դեպքում նկատի է առնվում էկոհամակարգը, որը այն համակարգն է, որտեղ օրգանիզմները փոխհարաբերվում են միմյանց, ինչպես նաև իրենց ֆիզիկական, կենսաբանական միջավայրի յուրաքանչյուր տարրի հետ։ Էվգեն Օդումը էկոլոգիայի հիմնադիրը, էկոլոգիան սահմանել է որպես՝ «Տվյալ տարածքում բոլոր օրգանիզմների ամբողջությունը, որոնք փոխհարաբերվում են ֆիզիկական միջավայրի հետ այնպես, որ էներգիայի հոսքը բերում է սննդային կառուցվածքի, կենսաբազմազանության և օրգանիզմների միջև նյութերի փոխանակման ստեղծմանը[42]։ Էկոհամակարգի յուրաքանչյուր օրգանիզմ զբաղեցնում է որոշակի տարածք՝ խուց կամ դիրք և որոշակի հարաբերությունների մեջ է էկոհամակարգի այլ հատվածների հետ։ Այս հարաբերությունները ներառում են օրգանիզմի կյանքի պատմությունը, նրա դիրքը սննդային շղթայում և աշխարհագրական տարածումը։ Բնության այսպիսի ընկալումը գիտնականներին թույլ է տալիս նկարագրել այն ուժերը, որոնք միասին ձևավորում են բնական ընտրությունը։

Բնական ընտրությունը կարող է ազդել կյանքի կազմավորման տարբեր մակարդակներում՝ գեներ, բջիջներ, օրգանիզմներ, օրգանիզմների կամ տեսակների խմբեր[43][44][45] ։ Բնական ընտրությունը կարող է միաժամանակ ընթանալ տարբեր մակարդակներում[46]։ Գենային մակարդակում տեղի ունեցող բնական ընտրության օրինակ են տրանսպոզոնները, որոնք կարող են կրկնապատկվել և տարածվել գենոմում[47]։ Առանձնյակի մակարդակից բարձր մակարդակներում ընթացող բնական ընտրությունը, օրինակ՝ խմբային ընտրությունը, կարող է բերել օրգանիզմների միջև համագործակցության ձևավորմանը[48]։

Կողմնակալ մուտացիաներ

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Բացի փոփոխականության կարևոր աղբյուր լինելուց, մուտացիաները մուտացիաները կարող են լինել նաև էվոլյուցիայի մեխանիմներ, երբ մոլեկուլային մակարդակում տարբեր մուտացիաների իրականացման համար կան տարբեր հավանականություններ, որը հայտնի է կողմնակալ մուտացիաներ անունով[49]։ Եթե երկու կան երկու գենոտիպներից նույն դիրքում մեկը ունի Գ նուկլեոտիդ, մյուսը՝ Ա և ունեն նույն հարմարողականությունը, բայց Գ-ից Ա մուտացիան ավելի հաճախ է իրականանում, քան՝ Ա-ից Գ-ն, ապա Ա-ով գենոտիպերը միտված են էվոլուցվել[50]։ Տարբեր տաքսոներում տարբեր ինսերցիաների և դելեցիաների կողմնակալ մուտացիաները բերում են տարբեր գենոմների չափերի առաջացման[51][52]։ Զարգացման և մուտացիաների կողմնակալությունները դիտարկվել են նաև ձևաբանական էվոլյուցիայում[53][54]։ Օրինակ՝ «սկզբում ֆենոտիպը» էվոլյուցիոն տեսության՝ մուտացիաները վերջում կարող են հանգեցնել միջավայրով պայմանավորված հատկանիշների գենետիկական ասիմիլյացիային[55][56][57]։

Կողմնակալ մուտացիաների ազդեցությունը ուսումնասիրվել է նաև այլ գործընթացներում։ Եթե ընտրությունը

Mutation bias effects are superimposed on other processes. If selection would favor either one out of two mutations, but there is no extra advantage to having both, then the mutation that occurs the most frequently is the one that is most likely to become fixed in a population.[58][59] Mutations leading to the loss of function of a gene are much more common than mutations that produce a new, fully functional gene. Most loss of function mutations are selected against. But when selection is weak, mutation bias towards loss of function can affect evolution.[60] For example, pigments are no longer useful when animals live in the darkness of caves, and tend to be lost.[61] This kind of loss of function can occur because of mutation bias, and/or because the function had a cost, and once the benefit of the function disappeared, natural selection leads to the loss. Loss of sporulation ability in Bacillus subtilis during laboratory evolution appears to have been caused by mutation bias, rather than natural selection against the cost of maintaining sporulation ability.[62] When there is no selection for loss of function, the speed at which loss evolves depends more on the mutation rate than it does on the effective population size,[63] indicating that it is driven more by mutation bias than by genetic drift. In parasitic organisms, mutation bias leads to selection pressures as seen in Ehrlichia. Mutations are biased towards antigenic variants in outer-membrane proteins.

Biased mutation

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]In addition to being a major source of variation, mutation may also function as a mechanism of evolution when there are different probabilities at the molecular level for different mutations to occur, a process known as mutation bias.[64] If two genotypes, for example one with the nucleotide G and another with the nucleotide A in the same position, have the same fitness, but mutation from G to A happens more often than mutation from A to G, then genotypes with A will tend to evolve.[65] Different insertion vs. deletion mutation biases in different taxa can lead to the evolution of different genome sizes.[66][67] Developmental or mutational biases have also been observed in morphological evolution.[68][69] For example, according to the phenotype-first theory of evolution, mutations can eventually cause the genetic assimilation of traits that were previously induced by the environment.[70][71][72]

Mutation bias effects are superimposed on other processes. If selection would favor either one out of two mutations, but there is no extra advantage to having both, then the mutation that occurs the most frequently is the one that is most likely to become fixed in a population.[73][74] Mutations leading to the loss of function of a gene are much more common than mutations that produce a new, fully functional gene. Most loss of function mutations are selected against. But when selection is weak, mutation bias towards loss of function can affect evolution.[75] For example, pigments are no longer useful when animals live in the darkness of caves, and tend to be lost.[76] This kind of loss of function can occur because of mutation bias, and/or because the function had a cost, and once the benefit of the function disappeared, natural selection leads to the loss. Loss of sporulation ability in Bacillus subtilis during laboratory evolution appears to have been caused by mutation bias, rather than natural selection against the cost of maintaining sporulation ability.[77] When there is no selection for loss of function, the speed at which loss evolves depends more on the mutation rate than it does on the effective population size,[78] indicating that it is driven more by mutation bias than by genetic drift. In parasitic organisms, mutation bias leads to selection pressures as seen in Ehrlichia. Mutations are biased towards antigenic variants in outer-membrane proteins.

Genetic drift

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

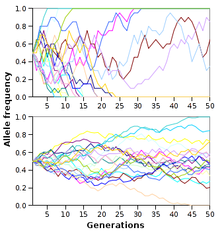

Genetic drift is the change in allele frequency from one generation to the next that occurs because alleles are subject to sampling error.[79] As a result, when selective forces are absent or relatively weak, allele frequencies tend to "drift" upward or downward randomly (in a random walk). This drift halts when an allele eventually becomes fixed, either by disappearing from the population, or replacing the other alleles entirely. Genetic drift may therefore eliminate some alleles from a population due to chance alone. Even in the absence of selective forces, genetic drift can cause two separate populations that began with the same genetic structure to drift apart into two divergent populations with different sets of alleles.[80]

It is usually difficult to measure the relative importance of selection and neutral processes, including drift.[81] The comparative importance of adaptive and non-adaptive forces in driving evolutionary change is an area of current research.[82]

The neutral theory of molecular evolution proposed that most evolutionary changes are the result of the fixation of neutral mutations by genetic drift.[83] Hence, in this model, most genetic changes in a population are the result of constant mutation pressure and genetic drift.[84] This form of the neutral theory is now largely abandoned, since it does not seem to fit the genetic variation seen in nature.[85][86] However, a more recent and better-supported version of this model is the nearly neutral theory, where a mutation that would be effectively neutral in a small population is not necessarily neutral in a large population.[87] Other alternative theories propose that genetic drift is dwarfed by other stochastic forces in evolution, such as genetic hitchhiking, also known as genetic draft.[79][88][89]

The time for a neutral allele to become fixed by genetic drift depends on population size, with fixation occurring more rapidly in smaller populations.[90] The number of individuals in a population is not critical, but instead a measure known as the effective population size.[91] The effective population is usually smaller than the total population since it takes into account factors such as the level of inbreeding and the stage of the lifecycle in which the population is the smallest.[91] The effective population size may not be the same for every gene in the same population.[92]

Genetic hitchhiking

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Recombination allows alleles on the same strand of DNA to become separated. However, the rate of recombination is low (approximately two events per chromosome per generation). As a result, genes close together on a chromosome may not always be shuffled away from each other and genes that are close together tend to be inherited together, a phenomenon known as linkage.[93] This tendency is measured by finding how often two alleles occur together on a single chromosome compared to expectations, which is called their linkage disequilibrium. A set of alleles that is usually inherited in a group is called a haplotype. This can be important when one allele in a particular haplotype is strongly beneficial: natural selection can drive a selective sweep that will also cause the other alleles in the haplotype to become more common in the population; this effect is called genetic hitchhiking or genetic draft.[94] Genetic draft caused by the fact that some neutral genes are genetically linked to others that are under selection can be partially captured by an appropriate effective population size.[88]

Gene flow

[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]Gene flow involves the exchange of genes between populations and between species.[95] The presence or absence of gene flow fundamentally changes the course of evolution. Due to the complexity of organisms, any two completely isolated populations will eventually evolve genetic incompatibilities through neutral processes, as in the Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller model, even if both populations remain essentially identical in terms of their adaptation to the environment.

If genetic differentiation between populations develops, gene flow between populations can introduce traits or alleles which are disadvantageous in the local population and this may lead to organisms within these populations evolving mechanisms that prevent mating with genetically distant populations, eventually resulting in the appearance of new species. Thus, exchange of genetic information between individuals is fundamentally important for the development of the biological species concept.

During the development of the modern synthesis, Sewall Wright developed his shifting balance theory, which regarded gene flow between partially isolated populations as an important aspect of adaptive evolution.[96] However, recently there has been substantial criticism of the importance of the shifting balance theory.[97]

- ↑ Sawyer, Stanley A.; Parsch, John; Zhang Zhi; Hartl, Daniel L. (April 17, 2007). «Prevalence of positive selection among nearly neutral amino acid replacements in Drosophila». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 104 (16): 6504–6510. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6504S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701572104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1871816. PMID 17409186.

- ↑ Hastings, P. J.; Lupski, James R.; Rosenberg, Susan M.; Ira, Grzegorz (August 2009). «Mechanisms of change in gene copy number». Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 10 (8): 551–564. doi:10.1038/nrg2593. ISSN 1471-0056. PMC 2864001. PMID 19597530.

- ↑ Carroll, Grenier & Weatherbee 2005[Հղում աղբյուրներին]

- ↑ Harrison, Paul M.; Gerstein, Mark (May 17, 2002). «Studying Genomes Through the Aeons: Protein Families, Pseudogenes and Proteome Evolution». Journal of Molecular Biology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 318 (5): 1155–1174. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00109-2. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 12083509.

- ↑ Bowmaker, James K. (May 1998). «Evolution of colour vision in vertebrates». Eye. London: Nature Publishing Group on behalf of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. 12 (3b): 541–547. doi:10.1038/eye.1998.143. ISSN 0950-222X. PMID 9775215.

- ↑ Gregory, T. Ryan; Hebert, Paul D. N. (April 1999). «The Modulation of DNA Content: Proximate Causes and Ultimate Consequences». Genome Research. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 9 (4): 317–324. doi:10.1101/gr.9.4.317. ISSN 1088-9051. PMID 10207154. Վերցված է 2014-12-11-ին.

- ↑ Hurles, Matthew (July 13, 2004). «Gene Duplication: The Genomic Trade in Spare Parts». PLOS Biology. San Francisco, CA: Public Library of Science. 2 (7): e206. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020206. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 449868. PMID 15252449.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 սպաս․ չպիտակված ազատ DOI (link) - ↑ Siepel, Adam (October 2009). «Darwinian alchemy: Human genes from noncoding DNA». Genome Research. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 19 (10): 1693–1695. doi:10.1101/gr.098376.109. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 2765273. PMID 19797681. Վերցված է 2014-12-11-ին.

- ↑ Liu, Na; Okamura, Katsutomo; Tyler, David M.; և այլք: (October 2008). «The evolution and functional diversification of animal microRNA genes». Cell Research. London: Nature Publishing Group on behalf of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences. 18 (10): 985–996. doi:10.1038/cr.2008.278. ISSN 1001-0602. PMC 2712117. PMID 18711447. Վերցված է 2014-12-11-ին.

- ↑ Long, Manyuan; Betrán, Esther; Thornton, Kevin; Wang, Wen (November 2003). «The origin of new genes: glimpses from the young and old». Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 4 (11): 865–875. doi:10.1038/nrg1204. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 14634634.

- ↑ Orengo, Christine A.; Thornton, Janet M. (July 2005). «Protein families and their evolution—a structural perspective». Annual Review of Biochemistry. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 74: 867–900. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133029. ISSN 0066-4154. PMID 15954844.

- ↑ Wang, Minglei; Caetano-Anollés, Gustavo (January 14, 2009). «The Evolutionary Mechanics of Domain Organization in Proteomes and the Rise of Modularity in the Protein World». Structure. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 17 (1): 66–78. doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.11.008. ISSN 1357-4310. PMID 19141283.

- ↑ Weissman, Kira J.; Müller, Rolf (April 14, 2008). «Protein–Protein Interactions in Multienzyme Megasynthetases». ChemBioChem. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. 9 (6): 826–848. doi:10.1002/cbic.200700751. ISSN 1439-4227. PMID 18357594.

- ↑ Radding, Charles M. (December 1982). «Homologous Pairing and Strand Exchange in Genetic Recombination». Annual Review of Genetics. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 16: 405–437. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.16.120182.002201. ISSN 0066-4197. PMID 6297377.

- ↑ Agrawal, Aneil F. (September 5, 2006). «Evolution of Sex: Why Do Organisms Shuffle Their Genotypes?». Current Biology. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 16 (17): R696–R704. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.063. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 16950096.

- ↑ Peters, Andrew D.; Otto, Sarah P. (June 2003). «Liberating genetic variance through sex». BioEssays. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. 25 (6): 533–537. doi:10.1002/bies.10291. ISSN 0265-9247. PMID 12766942.

- ↑ Goddard, Matthew R.; Godfray, H. Charles J.; Burt, Austin (March 31, 2005). «Sex increases the efficacy of natural selection in experimental yeast populations». Nature. London: Nature Publishing Group. 434 (7033): 636–640. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..636G. doi:10.1038/nature03405. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15800622.

- ↑ Maynard Smith 1978[Հղում աղբյուրներին]

- ↑ Ridley 1993[Հղում աղբյուրներին]

- ↑ Morjan, Carrie L.; Rieseberg, Loren H. (June 2004). «How species evolve collectively: implications of gene flow and selection for the spread of advantageous alleles». Molecular Ecology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. 13 (6): 1341–1356. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02164.x. ISSN 0962-1083. PMC 2600545. PMID 15140081.

- ↑ Boucher, Yan; Douady, Christophe J.; Papke, R. Thane; և այլք: (December 2003). «Lateral gene transfer and the origins of prokaryotic groups». Annual Review of Genetics. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 37: 283–328. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.050503.084247. ISSN 0066-4197. PMID 14616063.

- ↑ Walsh, Timothy R. (October 2006). «Combinatorial genetic evolution of multiresistance». Current Opinion in Microbiology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 9 (5): 476–482. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.009. ISSN 1369-5274. PMID 16942901.

- ↑ Kondo, Natsuko; Nikoh, Naruo; Ijichi, Nobuyuki; և այլք: (October 29, 2002). «Genome fragment of Wolbachia endosymbiont transferred to X chromosome of host insect». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 99 (22): 14280–14285. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914280K. doi:10.1073/pnas.222228199. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 137875. PMID 12386340.

- ↑ Sprague, George F., Jr. (December 1991). «Genetic exchange between kingdoms». Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 1 (4): 530–533. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(05)80203-5. ISSN 0959-437X. PMID 1822285.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 սպաս․ բազմաթիվ անուններ: authors list (link) - ↑ Gladyshev, Eugene A.; Meselson, Matthew; Arkhipova, Irina R. (May 30, 2008). «Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bdelloid Rotifers». Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 320 (5880): 1210–1213. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1210G. doi:10.1126/science.1156407. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18511688.

- ↑ Baldo, Angela M.; McClure, Marcella A. (September 1999). «Evolution and Horizontal Transfer of dUTPase-Encoding Genes in Viruses and Their Hosts». Journal of Virology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology. 73 (9): 7710–7721. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 104298. PMID 10438861.

- ↑ Rivera, Maria C.; Lake, James A. (September 9, 2004). «The ring of life provides evidence for a genome fusion origin of eukaryotes». Nature. London: Nature Publishing Group. 431 (7005): 152–155. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..152R. doi:10.1038/nature02848. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15356622.

- ↑ Ewens 2004[Հղում աղբյուրներին]

- ↑ Lewontin, R. C. (November 1970). «The Units of Selection» (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 1: 1–18. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.01.110170.000245. ISSN 1545-2069. JSTOR 2096764.

- ↑ 30,0 30,1 Hurst, Laurence D. (February 2009). «Fundamental concepts in genetics: genetics and the understanding of selection». Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 10 (2): 83–93. doi:10.1038/nrg2506. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 19119264.

- ↑ 31,0 31,1 31,2 Orr, H. Allen (August 2009). «Fitness and its role in evolutionary genetics». Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 10 (8): 531–539. doi:10.1038/nrg2603. ISSN 1471-0056. PMC 2753274. PMID 19546856.

- ↑ Lande, Russell; Arnold, Stevan J. (November 1983). «The Measurement of Selection on Correlated Characters». Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution. 37 (6): 1210–1226. doi:10.2307/2408842. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2408842.

- ↑ Futuyma 2005[Հղում աղբյուրներին]

- ↑ Goldberg, Emma E.; Igić, Boris (November 2008). «On phylogenetic tests of irreversible evolution». Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution. 62 (11): 2727–2741. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00505.x. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 18764918.

- ↑ Collin, Rachel; Miglietta, Maria Pia (November 2008). «Reversing opinions on Dollo's Law». Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 23 (11): 602–609. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.013. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 18814933.

- ↑ Hoekstra, Hopi E.; Hoekstra, Jonathan M.; Berrigan, David; և այլք: (July 31, 2001). «Strength and tempo of directional selection in the wild». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 98 (16): 9157–9160. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.9157H. doi:10.1073/pnas.161281098. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 55389. PMID 11470913.

- ↑ Felsenstein, Joseph (November 1979). «Excursions along the Interface between Disruptive and Stabilizing Selection». Genetics. Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America. 93 (3): 773–795. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1214112. PMID 17248980.

- ↑ Andersson, Malte; Simmons, Leigh W. (June 2006). «Sexual selection and mate choice» (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 21 (6): 296–302. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.015. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 16769428.

- ↑ Quinn, Thomas P.; Hendry, Andrew P.; Buck, Gregory B. (2001). «Balancing natural and sexual selection in sockeye salmon: interactions between body size, reproductive opportunity and vulnerability to predation by bears» (PDF). Evolutionary Ecology Research. 3: 917–937. ISSN 1522-0613. Վերցված է 2014-12-15-ին.

- ↑ Kokko, Hanna; Brooks, Robert; McNamara, John M.; Houston, Alasdair I. (July 7, 2002). «The sexual selection continuum». Proceedings of the Royal Society B. London: Royal Society. 269 (1498): 1331–1340. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2020. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1691039. PMID 12079655.

- ↑ Hunt, John; Brooks, Robert; Jennions, Michael D.; և այլք: (December 23, 2004). «High-quality male field crickets invest heavily in sexual display but die young». Nature. London: Nature Publishing Group. 432 (7020): 1024–1027. Bibcode:2004Natur.432.1024H. doi:10.1038/nature03084. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15616562.

- ↑ Odum 1971, էջ. 8

- ↑ Okasha 2006

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (February 28, 1998). «Gulliver's further travels: the necessity and difficulty of a hierarchical theory of selection». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. London: Royal Society. 353 (1366): 307–314. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0211. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1692213. PMID 9533127.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (March 18, 1997). «The objects of selection». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 94 (6): 2091–2094. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.2091M. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.6.2091. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 33654. PMID 9122151.

- ↑ Maynard Smith 1998, էջեր. 203–211, discussion 211–217

- ↑ Hickey, Donal A. (1992). «Evolutionary dynamics of transposable elements in prokaryotes and eukaryotes». Genetica. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 86 (1–3): 269–274. doi:10.1007/BF00133725. ISSN 0016-6707. PMID 1334911.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay; Lloyd, Elisabeth A. (October 12, 1999). «Individuality and adaptation across levels of selection: how shall we name and generalise the unit of Darwinism?». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 96 (21): 11904–11909. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9611904G. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.11904. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 18385. PMID 10518549.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (May 15, 2007). «The frailty of adaptive hypotheses for the origins of organismal complexity». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 104 (Suppl. 1): 8597–8604. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8597L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702207104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1876435. PMID 17494740.

- ↑ Smith, Nick G.C.; Webster, Matthew T.; Ellegren, Hans (September 2002). «Deterministic Mutation Rate Variation in the Human Genome». Genome Research. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 12 (9): 1350–1356. doi:10.1101/gr.220502. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 186654. PMID 12213772.

- ↑ Petrov, Dmitri A. (May 2002). «DNA loss and evolution of genome size in Drosophila». Genetica. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 115 (1): 81–91. doi:10.1023/A:1016076215168. ISSN 0016-6707. PMID 12188050.

- ↑ Petrov, Dmitri A.; Sangster, Todd A.; Johnston, J. Spencer; և այլք: (February 11, 2000). «Evidence for DNA Loss as a Determinant of Genome Size». Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 287 (5455): 1060–1062. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.1060P. doi:10.1126/science.287.5455.1060. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10669421.

- ↑ Kiontke, Karin; Barriere, Antoine; Kolotuev, Irina; և այլք: (November 2007). «Trends, Stasis, and Drift in the Evolution of Nematode Vulva Development». Current Biology. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 17 (22): 1925–1937. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.061. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 18024125.

- ↑ Braendle, Christian; Baer, Charles F.; Félix, Marie-Anne (March 12, 2010). Barsh, Gregory S. (ed.). «Bias and Evolution of the Mutationally Accessible Phenotypic Space in a Developmental System». PLOS Genetics. San Francisco, CA: Public Library of Science. 6 (3): e1000877. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000877. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 2837400. PMID 20300655.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 սպաս․ չպիտակված ազատ DOI (link) - ↑ Palmer, A. Richard (October 29, 2004). «Symmetry breaking and the evolution of development» (PDF). Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 306 (5697): 828–833. Bibcode:2004Sci...306..828P. doi:10.1126/science.1103707. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15514148.

- ↑ West-Eberhard 2003, էջեր. 140

- ↑ Pocheville, Arnaud; Danchin, Etienne (January 1, 2017). «Chapter 3: Genetic assimilation and the paradox of blind variation». In Huneman, Philippe; Walsh, Denis (eds.). Challenging the Modern Synthesis. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Stoltzfus, Arlin; Yampolsky, Lev Y. (September–October 2009). «Climbing Mount Probable: Mutation as a Cause of Nonrandomness in Evolution». Journal of Heredity. Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Genetic Association. 100 (5): 637–647. doi:10.1093/jhered/esp048. ISSN 0022-1503. PMID 19625453.

- ↑ Yampolsky, Lev Y.; Stoltzfus, Arlin (March 2001). «Bias in the introduction of variation as an orienting factor in evolution». Evolution & Development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. 3 (2): 73–83. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003002073.x. ISSN 1520-541X. PMID 11341676.

- ↑ Haldane, J. B. S. (January–February 1933). «The Part Played by Recurrent Mutation in Evolution». The American Naturalist. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. 67 (708): 5–19. doi:10.1086/280465. ISSN 0003-0147. JSTOR 2457127.

- ↑ Protas, Meredith; Conrad, Melissa; Gross, Joshua B.; և այլք: (March 6, 2007). «Regressive Evolution in the Mexican Cave Tetra, Astyanax mexicanus». Current Biology. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 17 (5): 452–454. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.051. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 2570642. PMID 17306543.

- ↑ Maughan, Heather; Masel, Joanna; Birky, C. William, Jr.; Nicholson, Wayne L. (October 2007). «The Roles of Mutation Accumulation and Selection in Loss of Sporulation in Experimental Populations of Bacillus subtilis». Genetics. Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America. 177 (2): 937–948. doi:10.1534/genetics.107.075663. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 2034656. PMID 17720926.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 սպաս․ բազմաթիվ անուններ: authors list (link) - ↑ Masel, Joanna; King, Oliver D.; Maughan, Heather (January 2007). «The Loss of Adaptive Plasticity during Long Periods of Environmental Stasis». The American Naturalist. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. 169 (1): 38–46. doi:10.1086/510212. ISSN 0003-0147. PMC 1766558. PMID 17206583.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (May 15, 2007). «The frailty of adaptive hypotheses for the origins of organismal complexity». Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 104 (Suppl. 1): 8597–8604. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8597L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702207104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1876435. PMID 17494740.

- ↑ Smith, Nick G.C.; Webster, Matthew T.; Ellegren, Hans (September 2002). «Deterministic Mutation Rate Variation in the Human Genome». Genome Research. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 12 (9): 1350–1356. doi:10.1101/gr.220502. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 186654. PMID 12213772.

- ↑ Petrov, Dmitri A.; Sangster, Todd A.; Johnston, J. Spencer; և այլք: (February 11, 2000). «Evidence for DNA Loss as a Determinant of Genome Size». Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 287 (5455): 1060–1062. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.1060P. doi:10.1126/science.287.5455.1060. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10669421.

- ↑ Petrov, Dmitri A. (May 2002). «DNA loss and evolution of genome size in Drosophila». Genetica. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 115 (1): 81–91. doi:10.1023/A:1016076215168. ISSN 0016-6707. PMID 12188050.

- ↑ Kiontke, Karin; Barriere, Antoine; Kolotuev, Irina; և այլք: (November 2007). «Trends, Stasis, and Drift in the Evolution of Nematode Vulva Development». Current Biology. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 17 (22): 1925–1937. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.061. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 18024125.

- ↑ Braendle, Christian; Baer, Charles F.; Félix, Marie-Anne (March 12, 2010). Barsh, Gregory S. (ed.). «Bias and Evolution of the Mutationally Accessible Phenotypic Space in a Developmental System». PLOS Genetics. San Francisco, CA: Public Library of Science. 6 (3): e1000877. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000877. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 2837400. PMID 20300655.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 սպաս․ չպիտակված ազատ DOI (link) - ↑ Palmer, A. Richard (October 29, 2004). «Symmetry breaking and the evolution of development» (PDF). Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 306 (5697): 828–833. Bibcode:2004Sci...306..828P. doi:10.1126/science.1103707. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15514148.

- ↑ West-Eberhard 2003, էջեր. 140

- ↑ Pocheville, Arnaud; Danchin, Etienne (January 1, 2017). «Chapter 3: Genetic assimilation and the paradox of blind variation». In Huneman, Philippe; Walsh, Denis (eds.). Challenging the Modern Synthesis. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Stoltzfus, Arlin; Yampolsky, Lev Y. (September–October 2009). «Climbing Mount Probable: Mutation as a Cause of Nonrandomness in Evolution». Journal of Heredity. Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Genetic Association. 100 (5): 637–647. doi:10.1093/jhered/esp048. ISSN 0022-1503. PMID 19625453.

- ↑ Yampolsky, Lev Y.; Stoltzfus, Arlin (March 2001). «Bias in the introduction of variation as an orienting factor in evolution». Evolution & Development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. 3 (2): 73–83. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003002073.x. ISSN 1520-541X. PMID 11341676.

- ↑ Haldane, J. B. S. (January–February 1933). «The Part Played by Recurrent Mutation in Evolution». The American Naturalist. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. 67 (708): 5–19. doi:10.1086/280465. ISSN 0003-0147. JSTOR 2457127.

- ↑ Protas, Meredith; Conrad, Melissa; Gross, Joshua B.; և այլք: (March 6, 2007). «Regressive Evolution in the Mexican Cave Tetra, Astyanax mexicanus». Current Biology. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 17 (5): 452–454. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.051. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 2570642. PMID 17306543.

- ↑ Maughan, Heather; Masel, Joanna; Birky, C. William, Jr.; Nicholson, Wayne L. (October 2007). «The Roles of Mutation Accumulation and Selection in Loss of Sporulation in Experimental Populations of Bacillus subtilis». Genetics. Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America. 177 (2): 937–948. doi:10.1534/genetics.107.075663. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 2034656. PMID 17720926.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 սպաս․ բազմաթիվ անուններ: authors list (link) - ↑ Masel, Joanna; King, Oliver D.; Maughan, Heather (January 2007). «The Loss of Adaptive Plasticity during Long Periods of Environmental Stasis». The American Naturalist. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. 169 (1): 38–46. doi:10.1086/510212. ISSN 0003-0147. PMC 1766558. PMID 17206583.

- ↑ 79,0 79,1 Masel, Joanna (October 25, 2011). «Genetic drift». Current Biology. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 21 (20): R837–R838. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.007. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 22032182.

- ↑ Lande, Russell (1989). «Fisherian and Wrightian theories of speciation». Genome. Ottawa: National Research Council of Canada. 31 (1): 221–227. doi:10.1139/g89-037. ISSN 0831-2796. PMID 2687093.

- ↑ Mitchell-Olds, Thomas; Willis, John H.; Goldstein, David B. (November 2007). «Which evolutionary processes influence natural genetic variation for phenotypic traits?». Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 8 (11): 845–856. doi:10.1038/nrg2207. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 17943192.

- ↑ Nei, Masatoshi (December 2005). «Selectionism and Neutralism in Molecular Evolution». Molecular Biology and Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (12): 2318–2342. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi242. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 1513187. PMID 16120807.

- Nei, Masatoshi (May 2006). «Selectionism and Neutralism in Molecular Evolution». Molecular Biology and Evolution (Erratum). Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (5): 1095. doi:10.1093/molbev/msk009. ISSN 0737-4038.

- ↑ Kimura, Motoo (1991). «The neutral theory of molecular evolution: a review of recent evidence». The Japanese Journal of Human Genetics. Mishima, Japan: Genetics Society of Japan. 66 (4): 367–386. doi:10.1266/jjg.66.367. ISSN 0021-504X. PMID 1954033.

- ↑ Kimura, Motoo (1989). «The neutral theory of molecular evolution and the world view of the neutralists». Genome. Ottawa: National Research Council of Canada. 31 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1139/g89-009. ISSN 0831-2796. PMID 2687096.

- ↑ Kreitman, Martin (August 1996). «The neutral theory is dead. Long live the neutral theory». BioEssays. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. 18 (8): 678–683, discussion 683. doi:10.1002/bies.950180812. ISSN 0265-9247. PMID 8760341.

- ↑ Leigh, E. G., Jr. (November 2007). «Neutral theory: a historical perspective». Journal of Evolutionary Biology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the European Society for Evolutionary Biology. 20 (6): 2075–2091. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01410.x. ISSN 1010-061X. PMID 17956380.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 սպաս․ բազմաթիվ անուններ: authors list (link) - ↑ Hurst, Laurence D. (February 2009). «Fundamental concepts in genetics: genetics and the understanding of selection». Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 10 (2): 83–93. doi:10.1038/nrg2506. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 19119264.

- ↑ 88,0 88,1 Gillespie, John H. (November 2001). «Is the population size of a species relevant to its evolution?». Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution. 55 (11): 2161–2169. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00732.x. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 11794777.

- ↑ Neher, Richard A.; Shraiman, Boris I. (August 2011). «Genetic Draft and Quasi-Neutrality in Large Facultatively Sexual Populations». Genetics. Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America. 188 (4): 975–996. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128876. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 3176096. PMID 21625002.

- ↑ Otto, Sarah P.; Whitlock, Michael C. (June 1997). «The Probability of Fixation in Populations of Changing Size» (PDF). Genetics. Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America. 146 (2): 723–733. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1208011. PMID 9178020. Վերցված է 2014-12-18-ին.

- ↑ 91,0 91,1 Charlesworth, Brian (March 2009). «Fundamental concepts in genetics: effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation». Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 10 (3): 195–205. doi:10.1038/nrg2526. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 19204717.

- ↑ Cutter, Asher D.; Choi, Jae Young (August 2010). «Natural selection shapes nucleotide polymorphism across the genome of the nematode Caenorhabditis briggsae». Genome Research. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 20 (8): 1103–1111. doi:10.1101/gr.104331.109. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 2909573. PMID 20508143.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(օգնություն) - ↑ Lien, Sigbjørn; Szyda, Joanna; Schechinger, Birgit; և այլք: (February 2000). «Evidence for Heterogeneity in Recombination in the Human Pseudoautosomal Region: High Resolution Analysis by Sperm Typing and Radiation-Hybrid Mapping». American Journal of Human Genetics. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press on behalf of the American Society of Human Genetics. 66 (2): 557–566. doi:10.1086/302754. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1288109. PMID 10677316.

- ↑ Barton, Nicholas H. (November 29, 2000). «Genetic hitchhiking». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. London: Royal Society. 355 (1403): 1553–1562. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0716. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1692896. PMID 11127900.

- ↑ Morjan, Carrie L.; Rieseberg, Loren H. (June 2004). «How species evolve collectively: implications of gene flow and selection for the spread of advantageous alleles». Molecular Ecology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. 13 (6): 1341–1356. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02164.x. ISSN 0962-1083. PMC 2600545. PMID 15140081.

- ↑ Wright, Sewall (1932). «The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding and selection in evolution». Proceedings of the VI International Congress of Genetrics. 1: 356–366. Վերցված է 2014-12-18-ին.

- ↑ Coyne, Jerry A.; Barton, Nicholas H.; Turelli, Michael (June 1997). «Perspective: A Critique of Sewall Wright's Shifting Balance Theory of Evolution». Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution. 51 (3): 643–671. doi:10.2307/2411143. ISSN 0014-3820.