«Մասնակից:Makruhi/Ավազարկղ ադ»–ի խմբագրումների տարբերություն

No edit summary |

|||

| Տող 7. | Տող 7. | ||

==Գույն== |

==Գույն== |

||

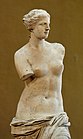

Հին աշխարհից պահպանված բազմաթիվ արձանները պարզորեն երևում են թե ինչից են պատրաստված։ Հին հունական արձանները քանդակված էին մարմարից,, սակայն կա ապացույց, որ նրանցից ոմանք ներկում էինն պայծառ գույներով։ <ref name=colorgods>{{cite web|url=http://www.archaeology.org/0801/trenches/colorgods.html |title=Archeological Institute of America: Carved in Living Color |publisher=Archaeology.org |date=23 June 2008 |accessdate=30 December 2012}}</ref> Գույներից ոմանք գունաթափվում էին ժամանակի ընթացքում, ոմանք արձանները մաքրելու ժամանակ, սակայն բոլոր դեպքերում էլ մնում էին հետքեր, որոնցով կարելի էր բնորոշել նրանց նախկին գույնը։<ref name=colorgods/> |

Հին աշխարհից պահպանված բազմաթիվ արձանները պարզորեն երևում են թե ինչից են պատրաստված։ Հին հունական արձանները քանդակված էին մարմարից,, սակայն կա ապացույց, որ նրանցից ոմանք ներկում էինն պայծառ գույներով։ <ref name=colorgods>{{cite web|url=http://www.archaeology.org/0801/trenches/colorgods.html |title=Archeological Institute of America: Carved in Living Color |publisher=Archaeology.org |date=23 June 2008 |accessdate=30 December 2012}}</ref> Գույներից ոմանք գունաթափվում էին ժամանակի ընթացքում, ոմանք արձանները մաքրելու ժամանակ, սակայն բոլոր դեպքերում էլ մնում էին հետքեր, որոնցով կարելի էր բնորոշել նրանց նախկին գույնը։<ref name=colorgods/> 20 գույներով հռոմեկան և հունական 35 բնօրինակ արձանների շրջիկ ցուցաահանդես կազմակերպվել է Եվրոպայում և ԱՄՆ–ում 2008 թվականին․ գունավոր Աստվածները․ Դասական հին աշխարհի ներկված քանդակակագործությունը։<ref name="artmuseums.harvard.edu">{{cite web|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20090104060402/http://www.artmuseums.harvard.edu/exhibitions/sackler/godsInColor.html |title=Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity September 22, 2007 Through January 20, 2008, The Arthur M. Sackler Museum |publisher=Web.archive.org |date=4 January 2009 |accessdate=30 December 2012}}</ref> Details such as whether the paint was applied in one or two coats, how finely the pigments were ground, or exactly which binding medium would have been used in each case—all elements that would affect the appearance of a finished piece—are not known. Richter goes so far as to say of classical Greek sculpture, "`All stone sculpture, whether limestone ir marble, was painted, either wholly or in part." <ref>Richter, Gosela M. A., ‘’The Handbook of Greek Art: Architecture, Sculpture, Gems, Coins, Jewellery, Metalwork, Pottery and Vase Painting, Glass, Furniture, Textiles, Paintings and Mosaics’’, Phaidon Publishers Inc., New York, 1960 p. 46</ref> |

||

Միջնադարյան արձանները սովորաբար նույնպես նեկվում էին, պահպանելով իրենց ինքնատիպ գծերը։ Արձանների ներիկելը դադարեցվում է Վերածննդի ժամանակաշրջանում, երբ պեղեցին դասական արձանները, որոնք արդեն կորցրել էին իրենց գույն, դիտվեցին որպես լավագույն նմուշներ։ |

|||

Medieval statues were also usually painted, with some still retaining their original pigments. The colouring of statues ceased during the Renaissance, as excavated classical sculptures, which had lost their colouring, became regarded as the best models. |

|||

==Historical periods== |

==Historical periods== |

||

08:33, 23 Հուլիսի 2014-ի տարբերակ

Արձանը դա մեկ կամ ավելի մարդկանց, կենդանիների ներկայացումն է քանդակագործության միջոցով, բնական չափսերով, կամ կիսանդրիի տեսքով, ավելի հսկայական չափերով, ընդհուպ մինչև այլաբանորեն ներկայացնելը։ [1] Կան նաև շատ փոքր չափի, որոնք հազիվ են տեղավորվում ձեռքի մեջ; Նմանատիպ քանդակները կոչվում են արձանիկներ։

Արձանները ստեղծվել են բազմաթիվ ազգային մշակույթներում սկսած նախապատմական շրջանից մինչև մեր օրերը։ Ամենահին հայտնի արձանը ստեղծվել է համարյա 30,000 տարի առաջ։ Աշխարհի ամենաերկար արձանի բարձրությունը հասնում է 500 ոտնաչափի։

Բազմաթիվ արձաններ ստեղծվել են հավերժացնելու այս կամ այն պատմական իրադարձություն, ոմանք էլ՝ հայտնի և ազդեցիկ մարդկանց հիշատակը։ կան բազմաթիվ քանդակներ, որոնք ստեղծվել են որպես հասարակական արվեստի գործ բացօդյա ցուցադրությունների կամ հասարակական կառույցներում ցուցադրելու համար։ Որոշ արձաններ հայտնի դառնալու իրավունքն են ձեռք բերել, անկախ որևէ մեկին կամ որևէ սկղբունք ներկայացնելու, որոնց թվում դասվում է Ազատության արձանը։

Գույն

Հին աշխարհից պահպանված բազմաթիվ արձանները պարզորեն երևում են թե ինչից են պատրաստված։ Հին հունական արձանները քանդակված էին մարմարից,, սակայն կա ապացույց, որ նրանցից ոմանք ներկում էինն պայծառ գույներով։ [2] Գույներից ոմանք գունաթափվում էին ժամանակի ընթացքում, ոմանք արձանները մաքրելու ժամանակ, սակայն բոլոր դեպքերում էլ մնում էին հետքեր, որոնցով կարելի էր բնորոշել նրանց նախկին գույնը։[2] 20 գույներով հռոմեկան և հունական 35 բնօրինակ արձանների շրջիկ ցուցաահանդես կազմակերպվել է Եվրոպայում և ԱՄՆ–ում 2008 թվականին․ գունավոր Աստվածները․ Դասական հին աշխարհի ներկված քանդակակագործությունը։[3] Details such as whether the paint was applied in one or two coats, how finely the pigments were ground, or exactly which binding medium would have been used in each case—all elements that would affect the appearance of a finished piece—are not known. Richter goes so far as to say of classical Greek sculpture, "`All stone sculpture, whether limestone ir marble, was painted, either wholly or in part." [4]

Միջնադարյան արձանները սովորաբար նույնպես նեկվում էին, պահպանելով իրենց ինքնատիպ գծերը։ Արձանների ներիկելը դադարեցվում է Վերածննդի ժամանակաշրջանում, երբ պեղեցին դասական արձանները, որոնք արդեն կորցրել էին իրենց գույն, դիտվեցին որպես լավագույն նմուշներ։

Historical periods

Antiquity

The Lion man from the Swabian Alps in Germany is the oldest known statue in the world, and dates to 30,000-40,000 years ago.[5][6][7] The Venus of Hohle Fels, from the same area, is somewhat later.[8] Throughout history, statues have been associated with cult images in many religious traditions, from Ancient Egypt, Ancient Greece, and Ancient Rome to the present.

Egyptian statues showing kings as sphinxes have existed since the Old Kingdom, the oldest being for Djedefre (c. 2500 BC).[9] The oldest statue of a striding pharaoh dates from the reign of Senwosret I (c. 1950 BC) and is the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.[10] The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (starting around 2000 BC) witnessed the growth of block statues which then became the most popular form until the Ptolemaic period (c. 300 BC).[11]

The oldest statue of a deity in Rome was the bronze statue of Ceres in 485 BC.[12][13] The oldest statue in Rome is now the statue of Diana on the Aventine.[14]

The wonders of the world include several statues from antiquity, with the Colossus of Rhodes and the Statue of Zeus at Olympia among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Middle Ages

While Byzantine art flourished in various forms, sculpture and statue making witnessed a general decline; although statues of emperors continued to appear.[15] An example was the statue of Justinian (6th century) which stood in the square across from the Hagia Sophia until the fall of Constantinople in the 15th century.[15] Part of the decline in statue making in the Byzantine period can be attributed to the mistrust the Church placed in the art form, given that it viewed sculpture in general as a method for making and worshiping idols.[15] While making statues was not subject to a general ban, it was hardly encouraged in this period.[15] Justinian was one of the last Emperors to have a full-size statue made, and secular statues of any size became virtually non-existent after iconoclasm; and the artistic skill for making statues was lost in the process.

Modern Era

Կաղապար:Contradict-other Starting with the work of Maillol around 1900, the human figures embodied in statues began to move away from the various schools of realism that had held them bound for thousands of years. The Futurist and Cubist schools took this metamorphism even further until statues, often still nominally representing humans, had lost all but the most rudimentary relationship to the human firm. By the 1920s and 1930s statues began to appear that were completely abstract in design and execution.[16]

The notion that the position of the hooves of horses in equestrian statues indicated the rider's cause of death has been disproved.[17][18]

Gallery

-

Lion man, from Hohlenstein-Stadel, Germany, now in Ulmer Museum, Ulm, Germany, the oldest known zoomorphic statuette, Aurignacian era, 40,000 BC-30,000 BC

-

Venus of Willendorf, one of the oldest known Statuettes, Upper Paleolithic, 24,000 BC-22,000 BC

-

Great Sphinx of Giza, c. 2558–2532 BC, the largest monolith statue in the world, standing 73.5 metres (241 ft) long, 6 metres (20 ft) wide, and 20.22 m (66.34 ft) high. Giza, Egypt.

-

The Charioteer of Delphi, 474 BC, Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece

-

Hermes and the Infant Dionysus by Praxiteles, 4th century BC, Archaeological Museum of Olympia, Greece

-

Moai of Easter Island facing inland, Ahu Tongariki, c. 1250 - 1500, restored by Chilean archaeologist Claudio Cristino in the 1990s

-

The Great Buddha of Kamakura, c. 1252, Japan

-

The Mermaid of Copenhagen, 1903

-

A closeup of the replica statue of Roman Emperor, Marcus Aurelius, 1981, The original c. 200 AD is in the nearby Capitoline Museum, Rome

-

The Ushiku Daibutsu, Amitabha Buddha, 1993, Japan. The third tallest statue in the world, overall 394 feet in height.

-

Spring Temple Buddha, the world's tallest statue, overall 502 feet in height, completed 2002, China.

-

Kailashnath Mahadev Statue, Bhaktapur, Nepal. The world's tallest Statue of Lord Shiva, 143 feet, 2003-Present.

See also

References

- ↑ Merriam Webster's Dictionary defines a statue as: "a three-dimensional representation usually of a person, animal, or mythical being that is produced by sculpturing, modeling, or casting" [1]

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 «Archeological Institute of America: Carved in Living Color». Archaeology.org. 23 June 2008. Վերցված է 30 December 2012-ին.

- ↑ «Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity September 22, 2007 Through January 20, 2008, The Arthur M. Sackler Museum». Web.archive.org. 4 January 2009. Վերցված է 30 December 2012-ին.

- ↑ Richter, Gosela M. A., ‘’The Handbook of Greek Art: Architecture, Sculpture, Gems, Coins, Jewellery, Metalwork, Pottery and Vase Painting, Glass, Furniture, Textiles, Paintings and Mosaics’’, Phaidon Publishers Inc., New York, 1960 p. 46

- ↑ "Lion man takes pride of place as oldest statue" by Rex Dalton, Nature 425, 7 (4 September 2003) doi:10.1038/425007a also Nature News 4 September 2003

- ↑ "Ice Age Lion Man is world’s earliest figurative sculpture" by Martin Bailey, The Art Newspaper 31 January 2013

- ↑ Musical behaviours and the archaeological record: a preliminary study, University of Cambridge

- ↑ Painted Caves: Palaeolithic Rock Art in Western Europe by Andrew J. Lawson (13 July 2012) ISBN 0199698228 Oxford UP page 125

- ↑ The Egyptian Museum in Cairo by Abeer El-Shahawy and Farid Atiya (10 November 2005) ISBN 9771721836 page 117

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt by Donald B. Redford (15 December 2000) ISBN 0195102347 page 230

- ↑ Egyptian Statues by Gay Robins (4 March 2008) ISBN 0747805202 page 28

- ↑ Famous Firsts in the Ancient Greek and Roman World by David Matz (Jun 2000) ISBN 0786405996 page 87

- ↑ The Art of Rome c.753 B.C.-A.D. 337 by Jerome Jordan Pollitt (30 June 1983) ISBN 052127365X page 19

- ↑ Samnium and the Samnites by E. T. Salmon (2 September 1967) ISBN 0521061857 page 181

- ↑ 15,0 15,1 15,2 15,3 Byzantine Art by Charles Bayet (1 October 2009) ISBN 1844846202 page 54

- ↑ Giedion-Welcker, Carola, ‘’Contemporary Sculpture: An Evolution in Volume and Space, A revised and Enlarged Edition’’, Faber and Faber, London, 1961 pp. X to XX

- ↑ Barbara Mikkelson (2 August 2007). «Statue of Limitations». Snopes.com. Վերցված է 9 June 2011-ին.

- ↑ Cecil Adams (6 October 1989). «In statues, does the number of feet the horse has off the ground indicate the fate of the rider?». The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader. Վերցված է 9 June 2011-ին.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(օգնություն)

External links

| Վիքիպահեստ նախագծում կարող եք այս նյութի վերաբերյալ հավելյալ պատկերազարդում գտնել Makruhi/Ավազարկղ ադ կատեգորիայում։ |