Մասնակից:ArthurZQ/Ավազարկղ Բ

Հարավային Ամերիկայի պատմությունը անցյալի, հատկապես գրավոր ապացույցների, բանահյուսությունների և ավանդույթների ուսումնասիրությունն է, որոնք սերնդեսերունդ փոխանցվել են Հարավային Ամերիկա մայրցամաքում: Մայրցամաքը դեռ բնիկ ժողովուրդների տունն է, որոնցից մի քանիսը բարձր քաղաքակրթություններ են կառուցել մինչև եվրոպացիների ժամանումը 1400-ականների վերջին և 1500-ականների սկզբին: Հարավային Ամերիկայի պատմությունն ունի մարդկային մշակույթների և քաղաքակրթության ձևերի լայն շրջանակ: Կարալ Սուպե քաղաքակրթությունը, որը նաև հայտնի է որպես Պերուի Նորտե Չիկո քաղաքակրթություն, ամերիկյան մայրցամաքի ամենահին քաղաքակրթությունն է և աշխարհի առաջին վեց անկախ քաղաքակրթություններից մեկը. այն եգիպտական բուրգերի ժամանակակիցն էր: Այն նախորդել է մեզոամերիկյան օլմեկներին գրեթե երկու հազարամյակ[1][2]։

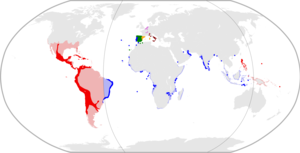

Բնիկ ժողովուրդների հազարամյա անկախ կյանքն ընդհատվեց Իսպանիայից և Պորտուգալիայից եվրոպական գաղութացման և ժողովրդագրական փլուզման պատճառով: Այնուամենայնիվ, արդյունքում առաջացած քաղաքակրթությունները մեծապես տարբերվում էին իրենց գաղութարարների քաղաքակրթություններից ՝ ինչպես մեստիզոյի, այնպես էլ մայրցամաքի բնիկ ժողովուրդների մշակույթում: Տրանսատլանտյան ստրկավաճառության շնորհիվ Հարավային Ամերիկան (հատկապես Բրազիլիան) դարձել է աֆրիկյան սփյուռքի միլիոնավոր ներկայացուցիչների տուն: Էթնիկ խմբերի խառնուրդը հանգեցրեց նոր սոցիալական կառույցների առաջացմանը:

Եվրոպացիների, բնիկ ժողովուրդների և աֆրիկացի ստրուկների և նրանց սերունդների միջև լարվածությունը ձևավորեց Հարավային Ամերիկան՝ սկսած 16-րդ դարից: Իսպանական Ամերիկայի մեծ մասը հասավ իր անկախությանը 19-րդ դարի սկզբին կատաղի պատերազմների արդյունքում, մինչդեռ պորտուգալական Բրազիլիան նախ դարձավ պորտուգալական կայսրության նստավայրը, իսկ ավելի ուշ՝ Պորտուգալիայից անկախ կայսրություն: 19-րդ դարում իսպանական թագից անկախության հեղափոխությամբ Հարավային Ամերիկան ենթարկվեց էլ ավելի սոցիալական և քաղաքական փոփոխությունների: Դրանք ներառում էին պետականաշինության նախագծեր, 19-րդ և 20-րդ դարերի վերջին Եվրոպայից ներգաղթի ալիքների կլանում ՝ կապված միջազգային առևտրի ընդլայնման, ներքին տարածքների գաղութացման և տարածքի տիրապետման և ուժերի հավասարակշռության պատերազմների հետ: Այս ժամանակահատվածում տեղի ունեցավ նաև բնիկ ժողովուրդների իրավունքների և պարտականությունների վերակազմավորում, պետությունների սահմաններում բնակվող բնիկ ժողովուրդների ենթակայություն, որը տևեց մինչև 1900-ականների սկիզբը։ Լիբերալ-պահպանողական հակամարտություններ իշխող խավերի միջև և ժողովրդագրական և բնապահպանական լուրջ փոփոխություններ, որոնք ուղեկցում են խոցելի բնակավայրերի զարգացմանը:

Նախապատմություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Պալեոզոյան և վաղ Մեզոզոյան դարաշրջանում Հարավային Ամերիկան և Աֆրիկան միացված էին Գոնդվանա կոչվող վարկածային մայրցամաքին՝ որպես Պանգեա գերմայրցամաքի մաս: Ալբիական ժամանակաշրջանում ՝ մոտ 110 միլիոն տարի առաջ, Հարավային Ամերիկան և Աֆրիկան սկսեցին ցրվել Հարավային միջինատլանտյան լեռնաշղթայի երկայնքով, որի արդյունքում ձևավորվեց Անտարկտիդայի և Հարավային Ամերիկայի ցամաքը: Ուշ էոցենում ՝ մոտ 35 միլիոն տարի առաջ, Անտարկտիդան և Հարավային Ամերիկան բաժանվեցին, և Հարավային Ամերիկան վերածվեց հսկայական, կենսաբանորեն հարուստ կղզի-մայրցամաքի: Մոտ 30 միլիոն տարվա ընթացքում Հարավային Ամերիկայի կենսաբանական բազմազանությունը մեկուսացվել է մնացած աշխարհից, ինչը հանգեցրել է մայրցամաքի ներսում տեսակների էվոլյուցիայի[3]:

66 միլիոն տարի առաջ դինոզավրերի զանգվածային ոչնչացման պատճառ դարձած իրադարձությունը հանգեցրեց նեոտրոպիկ անձրևային անտառների բիոմների առաջացմանը, ինչպիսին է Ամազոնիան՝ փոխարինելով բնիկ անտառների տեսակների կազմը և կառուցվածքը: Բույսերի բազմազանության նախկին մակարդակի վերականգնման 6 միլիոն տարվա ընթացքում դրանք զարգացել են լայնորեն տարածված, գերակշռող անտառներից մինչև խիտ պսակներով անտառներ, որոնք արգելափակում են արևի լույսը, գերակշռող ծաղկող բույսերը և բարձր ուղղահայաց շերտերը, որոնք հայտնի են այսօր[4][5]:

Երկրաբանական ապացույցները ցույց են տալիս, որ մոտ 3 միլիոն տարի առաջ Հարավային Ամերիկան կապվեց Հյուսիսային Ամերիկայի հետ, երբ անհետացավ Բոլիվարյան խրամատի ծովային պատնեշը և ձևավորվեց Պանամայի ցամաքային կամուրջը: Այս երկու ցամաքային զանգվածների միացումը հանգեցրեց ամերիկյան Մեծ փոխանակմանը, որի ընթացքում երկու մայրցամաքների բիոտան ընդլայնեց իր տիրույթները[3]: Առաջին Հայտնի տեսակը, որը գաղթեց դեպի հյուսիս, Pliometanastes-ն էր, որը մոտավորապես ժամանակակից Սև արջի չափ էր[3]: Դեպի Հարավային կիսագունդ միգրացիաները ձեռնարկվել են Հյուսիսային Ամերիկայի մի քանի մսակեր կաթնասունների կողմից: Հյուսիսամերիկյան կենդանական աշխարհի ընդլայնման արդյունքը զանգվածային ոչնչացումն էր, որի արդյունքում հարյուրավոր տեսակներ անհետացան համեմատաբար կարճ ժամանակում: Ժամանակակից հարավամերիկյան կաթնասունների մոտ 60%-ը սերում է հյուսիսամերիկյան տեսակներից[3]։ Հարավային Ամերիկայի որոշ տեսակներ կարողացան հարմարվել և տարածվել Հյուսիսային Ամերիկայում: Բացի Pliometanastes-ից, կաթնասունների ցամաքային փուլերի իրվինգթոնի փուլում, մոտ 1,9 միլիոն տարի առաջ, այնպիսի տեսակներ, ինչպիսիք են պամպատերիումը, հսկա արմադիլոն, հսկա մրջնակեր միրմեկոֆագան, նեոգեն կապիբարան (Hydrochoerus), Մեյզոնիքսը, գնացին դեպի հյուսիս[3]: Սարսափելի Տիտանիս թռչունը՝ Հարավային Ամերիկայի միակ խոշոր գիշատիչ կենդանին, տարածվել Է Հյուսիսային Ամերիկայում[3]։

Մինչկոլումբոսյան դարաշրջան[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ամենավաղ բնակիչները[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The Americas are thought to have been first inhabited by people from eastern Asia who crossed the Bering Land Bridge to present-day Alaska; the land separated and the continents are divided by the Bering Strait. Over the course of millennia, three waves of migrants spread to all parts of the Americas.[6] Genetic and linguistic evidence has shown that the last wave of migrant peoples settled across the northern tier, and did not reach South America.

Amongst the oldest evidence for human presence in South America is the Monte Verde II site in Chile, suggested to date to around 14,500 years ago.[7] From around 13,000 years ago, the Fishtail projectile point style became widespread across South America, with its disppearance around 11,000 years ago coincident with the disappearance of South America's megafauna as part of the Quaternary extinction event.[8]

Գյուղատնտեսություն և կենդանիների ընտելացում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The first evidence for the existence of agricultural practices in South America dates back to circa 6500 BCE, when potatoes, chilies and beans began to be cultivated for food in the Amazon Basin. Pottery evidence suggests that manioc, which remains a staple food supply today, was being cultivated as early as 2000 BCE.[9]

South American cultures began domesticating llamas and alpacas in the highlands of the Andes circa 3500 BCE. These animals were used for both transportation and meat; their fur was shorn or collected to use to make clothing.[9] Guinea pigs were also domesticated as a food source at this time.[10]

By 2000 BCE, many agrarian village communities had developed throughout the Andes and the surrounding regions. Fishing became a widespread practice along the coast, with fish being the primary source of food for those communities. Irrigation systems were also developed at this time, which aided in the rise of agrarian societies.[9] The food crops were quinoa, corn, lima beans, common beans, peanuts, manioc, sweet potatoes, potatoes, oca and squashes.[11] Cotton was also grown and was particularly important as the only major fiber crop.[9]

Among the earliest permanent settlements, dated to 4700 BC is the Huaca Prieta site on the coast of Peru, and at 3500 BC the Valdivia culture in Ecuador. Other groups also formed permanent settlements. Among those groups were the Muisca or "Muysca," and the Tairona, located in present-day Colombia. The Cañari of Ecuador, Quechua of Peru, and Aymara of Bolivia were the three most important Native peoples who developed societies of sedentary agriculture in South America.

In the last two thousand years, there may have been contact with the Polynesians who sailed to and from the continent across the South Pacific Ocean. The sweet potato, which originated in South America, spread through some areas of the Pacific. There is no genetic legacy of human contact.[12]

Կարալ Սուպե կամ Նորտե Չիկո[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

On the north-central coast of present-day Peru, the Caral-Supe civilization, also known as the Norte Chico civilization emerged as one of six civilizations to develop independently in the world. It was roughly contemporaneous with the Egyptian pyramids. It preceded the civilization of Mesoamerica by two millennia. It is believed to have been the only civilization dependent on fishing rather than agriculture to support its population.[13]

The Caral Supe complex is one of the larger Norte Chico sites and has been dated to 27th century BCE. It is noteworthy for having absolutely no signs of warfare. It was contemporary with urbanism's rise in Mesopotamia.[14]

Կանյարի[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The Cañari were the indigenous natives of today's Ecuadorian provinces of Cañar and Azuay at the time of European contact. They were an elaborate civilization with advanced architecture and religious belief. Most of their remains were either burned or destroyed from attacks by the Inca and later the Spaniards. Their old city "Guapondelig", was replaced twice, first by the Incan city of Tomipamba, and later by the colonial city of Cuenca.[15] The city was believed by the Spanish to be the site of El Dorado, the city of gold from the mythology of Colombia.

The Cañari were most notable in having repulsed the Incan invasion with fierce resistance for many years until they fell to Tupac Yupanqui. It is said that the Inca strategically married the Cañari princess Paccha to conquer the people. Many of their descendants still reside in Cañar.[16]

Չիբչանի ժողովուրդներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The Chibcha-speaking communities were the most numerous, the most extended by territory, and the most socio-economically developed of the Pre-Hispanic Colombian cultures. They were divided into two linguistic subgroups; the Arwako-Chimila languages, with the Tairona, Kankuamo, Kogi, Arhuaco, Chimila and Chitarero people and the Kuna-Colombian languages with Kuna, Nutabe, Motilon, U'wa, Lache, Guane, Sutagao and Muisca.[17]

Մուիսկա[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Of these indigenous groups, the Muisca were the most advanced and formed one of the four grand civilisations in the Americas.[18] With the Inca in Peru, they constituted the two developed and specialised societies of South America. The Muisca, meaning "people" or "person" in their version of the Chibcha language; Muysccubun,[19] inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the high plateau in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes and surrounding valleys, such as the Tenza Valley.[20] Commonly set at 800 AD, their history succeeded the Herrera Period.[21] The people were organised in a loose confederation of rulers, later called the Muisca Confederation.[22] At the time of the Spanish conquest, their reign spread across the modern departments Cundinamarca and Boyacá with small parts of southern Santander with a surface area of approximately 25,000 կիլոմետր քառակուսիs (9,700 sq mi) and a total population of between 300,000 and two million individuals.[23][24][25]

The Muisca were known as "The Salt People", thanks to their extraction of and trade in halite from brines in various salt mines of which those in Zipaquirá and Nemocón are still the most important. This extraction process was the work of the Muisca women exclusively and formed the backbone of their highly regarded trading with other Chibcha-, Arawak- and Cariban-speaking neighboring indigenous groups.[26][27] Trading was performed using salt, small cotton cloths and larger mantles and ceramics as barter trade.[28] Their economy was agricultural in nature, profiting from the fertile soils of the Pleistocene Lake Humboldt that existed on the Bogotá savanna until around 30,000 years BP. Their crops were cultivated using irrigation and drainage on elevated terraces and mounds.[27][29][30] To the Spanish conquistadors they were best known for their advanced gold-working, as represented in the tunjos (votive offer pieces), spread in museum collections all around the world. The famous Muisca raft, centerpiece in the collection of the Museo del Oro in the Colombian capital Bogotá, shows the skilled goldworking of the inhabitants of the Altiplano. The Muisca were the only pre-Columbian civilization known in South America to have used coins (tejuelos).[31]

The gold and tumbaga (a gold-silver-copper alloy elaborated by the Muisca) created the legend of El Dorado; the "land, city or man of gold". The Spanish conquistadors who landed in the Caribbean city of Santa Marta were informed of the rich gold culture and led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and his brother Hernán Pérez, organised the most strenuous of the Spanish conquests into the heart of the Andes in April 1536. After an expedition of a year, where 80% of the soldiers died due to the harsh climate, carnivores such as caimans and jaguars and the frequent attacks of the indigenous peoples found along the route, Tisquesusa, the zipa of Bacatá, on the Bogotá savanna, was beaten by the Spanish on April 20, 1537, and died "bathing in his own blood", as prophesied by the mohan Popón.[32]

Ամազոն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

For a long time, scholars believed that Amazon forests were occupied by small numbers of hunter-gatherer tribes. Archeologist Betty J. Meggers was a prominent proponent of this idea, as described in her book Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise. However, recent archeological findings have suggested that the region was densely populated. From the 1970s, numerous geoglyphs have been discovered on deforested land dating between 0–1250 AD. Additional finds have led to conclusions that there were highly developed and populous cultures in the forests, organized as Pre-Columbian civilizations.[33] The BBC's Unnatural Histories claimed that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristine wilderness, has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such as forest gardening.[34]

The first European to travel the length of the Amazon River was Francisco de Orellana in 1542.[35] The BBC documentary Unnatural Histories presents evidence that Francisco de Orellana, rather than exaggerating his claims as previously thought, was correct in his observations that an advanced civilization was flourishing along the Amazon in the 1540s. It is believed that the civilization was later devastated by the spread of infectious diseases from Europe, such as smallpox, to which the natives had no immunity.[34] Some 5 million people may have lived in the Amazon region in 1500, divided between dense coastal settlements, such as that at Marajó, and inland dwellers.[36] By 1900 the population had fallen to 1 million, and by the early 1980s, it was less than 200,000.[36]

Researchers have found that the fertile terra preta (black earth) is distributed over large areas in the Amazon forest. It is now widely accepted that these soils are a product of indigenous soil management. The development of this soil enabled agriculture and silviculture to be conducted in the previously hostile environment. Large portions of the Amazon rainforest are therefore probably the result of centuries of human management, rather than naturally occurring as has previously been supposed.[37] In the region of the Xinguanos tribe, remains of some of these large, mid-forest Amazon settlements were found in 2003 by Michael Heckenberger and colleagues of the University of Florida. Among those remains were evidence of constructed roads, bridges and large plazas.[38]

Անդյան քաղաքակրթություններ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Չավին[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The Chavín, a South American preliterate civilization, established a trade network and developed agriculture by 900 BCE, according to some estimates and archeological finds. Artifacts were found at a site called Chavín de Huantar in modern Peru at an elevation of 3,177 meters.[39] Chavín civilization spanned 900 to 200 BCE.[40]

Մոչե[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The Moche thrived on the north coast of Peru between the first and ninth century CE.[41] The heritage of the Moche comes down to us through their elaborate burials, excavated by former UCLA professor Christopher B. Donnan in association with the National Geographic Society.[42]

Skilled artisans, the Moche were a technologically advanced people who traded with faraway peoples, like the Maya. Knowledge about the Moche has been derived mostly from their ceramic pottery, which is carved with representations of their daily lives. They practiced human sacrifice, had blood-drinking rituals, and their religion incorporated non-procreative sexual practices (such as fellatio).[43][44]

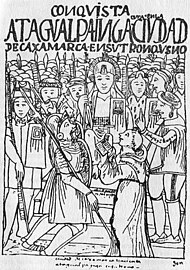

Ինկա[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Holding their capital at the great puma-shaped city of Cuzco, the Inca civilization dominated the Andes region from 1438 to 1533. Known as Tawantin suyu, or "the land of the four regions," in Quechua, the Inca civilization was highly distinct and developed. Inca rule extended to nearly a hundred linguistic or ethnic communities, some 9 to 14 million people connected by a 25,000-kilometre road system. Cities were built with precise, unmatched stonework, constructed over many levels of mountain terrain. Terrace farming was a useful form of agriculture. There is evidence of excellent metalwork and successful skull surgery in Inca civilization. The Inca had no written language, but used quipu, a system of knotted strings, to record information. [45] See notes.

Արավակի և Կարիբի քաղաքակրթությունները[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The Arawak lived along the eastern coast of South America, from present-day Guayana to as far south as what is now Brazil. Explorer Christopher Columbus described them at first encounter as a peaceful people, having already dominated other local groups such as the Ciboney. The Arawak had, however, come under increasing military pressure from the Carib, who are believed to have left the Orinoco river area to settle on islands and the coast of the Caribbean Sea. Over the century leading up to Columbus' arrival in the Caribbean archipelago in 1492, the Carib are believed to have displaced many of the Arawak who previously settled the island chains. The Carib also encroached on Arawak territory in what is modern Guyana.

The Carib were skilled boatbuilders and sailors who owed their dominance in the Caribbean basin to their military skills. The Carib war rituals included cannibalism; they had a practice of taking home the limbs of victims as trophies.

It is not known how many indigenous peoples lived in Venezuela and Colombia before the Spanish Conquest; it may have been approximately one million,[46] including groups such as the Auaké, Caquetio, Mariche, and Timoto-cuicas.[47] The number of people fell dramatically after the Conquest, mainly due to high mortality rates in epidemics of infectious Eurasian diseases introduced by the explorers, who carried them as an endemic disease.[46] There were two main north–south axes of pre-Columbian population; producing maize in the west and manioc in the east.[46] Large parts of the llanos plains were cultivated through a combination of slash and burn and permanent settled agriculture.[46]

Եվրոպական գաղութացում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Մինչև եվրոպացիների ժամանումը Հարավային Ամերիկայում ապրում էր 20-30 միլիոն մարդ[48]։

1452-1493 թվականներին պապական բուլեր (Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontifex և Inter caetera) նոր աշխարհում ճանապարհ հարթեցին եվրոպական գաղութացման և կաթոլիկ առաքելությունների համար: Նրանք թույլ տվեցին եվրոպական քրիստոնյա ազգերին «տիրել» ոչ քրիստոնեական հողերին և խրախուսեցին Աֆրիկայի և Ամերիկայի ոչ քրիստոնյա ժողովուրդների հպատակությունն ու դարձը[փա՞ստ]։

1494 թվականին Պորտուգալիան և Իսպանիան՝ ժամանակի երկու մեծ ծովային տերությունները, ստորագրեցին Տորդեսիլյասի պայմանագիրը՝ սպասելով Արևմուտքում նոր հողերի հայտնաբերմանը ։ Պայմանագրի համաձայն ՝ նրանք համաձայնել են, որ Եվրոպայից դուրս գտնվող բոլոր հողերը պետք է լինեն բացառիկ երկիշխանություն երկու երկրների միջև։ Պայմանագրով ստեղծվել է երևակայական գիծ Հյուսիսհարավ միջօրեականի երկայնքով՝ հրվանդանի կղզիներից 370 լիգա դեպի արևմուտք, մոտավորապես 46° 37' արևմտյան երկայնություն: Պայմանագրի պայմանների համաձայն, գծից արևմուտք գտնվող բոլոր հողերը (որոնք այժմ հայտնի են, որ ներառում են հարավամերիկյան տարածքի մեծ մասը) պատկանելու են Իսպանիային, իսկ արևելքում գտնվող բոլոր հողերը ՝ Պորտուգալիային: Քանի որ այդ ժամանակ երկայնության ճշգրիտ չափումները հնարավոր չէին, գիծը խստորեն չպահպանվեց, ինչը հանգեցրեց Բրազիլիայի պորտուգալական ընդլայնմանը միջօրեականի երկայնքով[փա՞ստ]:

1498 թվականին, Ամերիկա կատարած իր երրորդ ճանապարհորդության ժամանակ, Քրիստոֆեր Կոլումբոսը նավարկեց Օրինոկո Դելտայի մոտ, այնուհետև իջավ Պարիա ծոցում (ներկայիս Վենեսուելա): Զարմանալով քաղցրահամ ջրի հզոր առափնյա պաշարներով, Կոլումբոսը Իզաբելլա I-ին և Ֆերդինանդ II-ին ուղղված իր հուզիչ նամակում հայտնեց, որ նա հասել է դրախտ երկրի վրա:

1499 թվականից սկսած ՝ Հարավային Ամերիկայի բնակչությունն ու բնական պաշարները բազմիցս շահագործվել են օտարերկրյա նվաճողների կողմից ՝ Նախ Իսպանիայի, ապա Պորտուգալիայի: Այս մրցակից գաղութային տերությունները հայտարարեցին հողի և ռեսուրսների նկատմամբ իրենց իրավունքները և բաժանեցին այն գաղութների[49]:

Եվրոպական հիվանդությունները (ջրծաղիկ, գրիպ, կարմրուկ և տիֆ), որոնց նկատմամբ բնիկ բնակչությունը դիմադրություն չուներ, Ամերիկայի բնիկ բնակչության ապաբնակեցման հիմնական պատճառն էին[50]: Իսպանիայի վերահսկողության տակ գտնվող բռնի հարկադիր աշխատանքային համակարգերը (ինչպիսիք են էնկոմիենդասը և mita-ն հանքարդյունաբերության մեջ) նույնպես նպաստեցին բնակչության տեղահանմանը: Ստորին սահմանի գնահատականները խոսում են բնակչության մոտ 20-50 տոկոս կրճատման մասին, մինչդեռ բարձր գնահատականները հասնում են 90 տոկոսի[51]: Դրանից հետո նրանց արագ փոխարինեցին ստրկացած Աֆրիկացիները, որոնց մոտ իմունիտետ էր առաջացել այդ հիվանդությունների նկատմամբ[52]։

Իսպանացիները, հավատարիմ մնալով իրենց՝ ամերիկացի հպատակներին քրիստոնեություն դարձնելու ծրագրին, արագորեն ոչնչացրեցին տեղական մշակութային սովորույթները, որոնք խոչընդոտում էին այդ նպատակին: Այնուամենայնիվ, այս ուղղությամբ նախնական փորձերի մեծ մասը միայն մասամբ էր հաջող. ամերիկյան խմբերը պարզապես խառնում էին կաթոլիկությունը իրենց ավանդական հավատալիքների հետ: Իսպանացիները չեն պարտադրել իրենց լեզուն այնքանով, որքանով պարտադրել են իրենց կրոնը: Փաստորեն, Հռոմեական կաթոլիկ եկեղեցու միսիոներական գործունեությունը Կեչուա, Նահուատլ և Գուարանի լեզուներով իրականում նպաստեց այս ամերիկյան լեզուների տարածմանը՝ դրանք մատակարարելով գրային համակարգերով[փա՞ստ]:

Ի վերջո, բնիկներն ու իսպանացիները խաչասերվեցին ՝ կազմելով մետիսների դաս: Մետիսները և բնիկ ամերիկացիները հաճախ ստիպված էին անարդար հարկեր վճարել Իսպանիայի կառավարությանը (չնայած հարկերը վճարում էին բոլոր հպատակները) և խստորեն պատժվում էին իրենց օրենքներին չենթարկվելու համար: Տեղական արվեստի շատ գործեր համարվում էին հեթանոսական կուռքեր և ոչնչացվեցին իսպանացի հետազոտողների կողմից: Սա ներառում էր մեծ թվով ոսկե և արծաթե քանդակներ, որոնք հալվել էին նախքան Եվրոպա ուղարկվելը[53]:

17-րդ և 18-րդ դարեր[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

1616 թվականին Հոլանդացիները Էլդորադոյի լեգենդով ոգևորված, հիմնեցին բերդ Գուայանայում և հաստատեցին երեք գաղութներ[54]։

1624 թվականին Ֆրանսիան փորձեց բնակություն հաստատել ներկայիս Ֆրանսիական Գվիանայի տարածքում, բայց ստիպված եղավ հրաժարվել դրանից ՝ Ի դեմս պորտուգալացիների թշնամանքի, որոնք դա դիտում էին որպես Տորդեսիլյասի խաղաղության պայմանագրի խախտում: Այնուամենայնիվ, ֆրանսիացիները վերադարձան 1630 թվականին և 1643 թվականին Նրանց հաջողվեց բնակություն հաստատել Կայեննայում ՝ մի քանի փոքր տնկարկներով[փա՞ստ]:

16-րդ դարից սկսած ՝ իսպանական և պորտուգալական գաղութային համակարգից դժգոհության մի քանի շարժումներ են եղել։ Այս շարժումների շարքում առավել հայտնի էր Մարոնների շարժումը. ստրուկներ, ովքեր փախան իրենց տերերից և անտառային համայնքների քողի տակ կազմակերպեցին ազատ համայնքներ: Թագավորական բանակի կողմից նրանց իրենց հպատակեցնելու փորձերը ձախողվեցին, քանի որ մարոնները սովորեցին ապրել հարավամերիկյան ջունգլիներին: 1713 թվականի թագավորական հրամանագրով թագավորը օրինականություն տվեց մայրցամաքի առաջին ազատ բնակչությանը՝ ներկայիս Կոլումբիայի Պալենկե դե Սան Բազիլիոն, որը ղեկավարում էր Բենկոս Բիոհոն: Բրազիլիան ականատես եղավ իր հողում իսկական Աֆրիկյան Թագավորության ձևավորմանը՝ Պալմարիսը[փա՞ստ]:

1721-1735 թվականներին Պարագվայի կոմուներոսի ապստամբությունը տեղի ունեցավ պարագվայցի բնակիչների և ճիզվիտների միջև բախումների պատճառով, որոնք ղեկավարում էին խոշոր և բարգավաճ ճիզվիտական համայնքները և վերահսկում էին մեծ թվով քրիստոնեություն ընդունած բնիկների[փա՞ստ]:

1742-1756 թվականներին Պերուի Կենտրոնական ջունգլիներում տեղի ունեցավ Խուան Սանտոս Աթահուալպայի ապստամբությունը։ 1780 թվականին Պերուի փոխարքայությունը բախվեց կուրակ Ջոզեֆ Գաբրիել Կոնդորկանկիի կամ Տուպակ Ամարուիի-ի ապստամբությանը, որը շարունակվեց վերին Պերուում Տուպակ Կատարիի կողմից[փա՞ստ]։

1763 թվականին աֆրիկացի Քոֆին առաջնորդեց Գայանայի ապստամբությունը, որը արյունահեղորեն ճնշվեց հոլանդացիների կողմից[55]։ 1781 թվականին կոմուներոսի ապստամբությունը (Նոր Գրանադա), գյուղացիների ապստամբությունը Նոր Գրանադայի փոխարքայությունում, ժողովրդական հեղափոխություն էր, որը միավորում էր բնիկ բնակչությանը և մետիսներին։ Գյուղացիները փորձեցին դառնալ գաղութային տերություն, և չնայած հանձնման՝ կապիտուլիացիայի ստորագրմանը, փոխարքա Մանուել Անտոնիո Ֆլորեսը չհնազանդվեց և փոխարենը դիմեց գլխավոր առաջնորդներին՝ Խոսե Անտոնիո Գալանին:

1796 թվականին Էսսեկիբոյի հոլանդական գաղութը գրավվեց անգլիացիների կողմից ֆրանսիական հեղափոխական պատերազմների ժամանակ[56]։

1806-1807 թվականներին Բրիտանական զինված ուժերը փորձեցին ներխուժել Ռիո դե լա Պլատա տարածք՝ Հոմս Ռիգս Պոպհեմի, Ուիլյամ քար Բերեսֆորդի և Ջոն Ուայթլոկի հրամանատարությամբ։ Արշավանքները հետ մղվեցին, բայց մեծապես ազդեցին իսպանական իշխանության վրա[փա՞ստ]:

Անկախություն և 19-րդ դար[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Իսպանական գաղութները նվաճեցին իրենց անկախությունը 19-րդ դարի առաջին քառորդում՝ իսպանա-ամերիկյան անկախության պատերազմների ընթացքում։ Սիմոն Բոլիվարը (Մեծ Կոլումբիա, Պերու, Բոլիվիա), Խոսե դե Սան Մարտինը (Ռիվեր Փլեյթ, Չիլի և Պերու) և Բերնարդո Օ'Հիգինսը (Չիլի) առաջնորդեցին իրենց պայքարը անկախության համար: Չնայած Բոլիվարը փորձեց պահպանել մայրցամաքի իսպանախոս մասերի քաղաքական միասնությունը, այնուամենայնիվ նրանք արագորեն անկախացան միմյանցից:

Ի տարբերություն իսպանական գաղութների, Բրազիլիայի անկախությունը Պորտուգալիա նապոլեոնյան արշավանքների անուղղակի հետևանքն էր. ֆրանսիական ներխուժումը գեներալ Յունոտի հրամանատարությամբ հանգեցրեց Լիսաբոնի գրավմանը 1807 թվականի դեկտեմբերի 8-ին: Իր ինքնիշխանությունը չկորցնելու համար Պորտուգալիայի արքունիքը մայրաքաղաքը Լիսաբոնից տեղափոխեց Ռիո դե Ժանեյրո որը Պորտուգալիայի կայսրության մայրաքաղաքն էր 1808-1821 թվականներին և մեծացրեց Բրազիլիայի կարևորությունը պորտուգալական կայսրության շրջանակներում: 1820 թվականի Պորտուգալիայի ազատական հեղափոխությունից և Պարայում և Բահիայում մի քանի մարտերից և փոխհրաձգություններից հետո Պեդրոն՝ Պորտուգալիայի թագավոր Հովհաննես VI-ի որդին, 1822 թվականին հռչակեց երկրի անկախությունը և դարձավ Բրազիլիայի առաջին կայսրը (Հետագայում նա նաև ղեկավարեց որպես Պեդրու IV Պորտուգալացի): Դա մարդկության պատմության մեջ երբևէ տեսած ամենախաղաղ գաղութային անկախություններից մեկն էր:

Իշխանության համար պայքարը սկսվեց նոր ազգերի միջև, և շուտով հաջորդեցին ևս մի քանի պատերազմներ:

Առաջին մի քանի պատերազմները մղվեցին մայրցամաքի հյուսիսային և հարավային մասերում գերիշխանության համար: Հյուսիսային պատերազմը Գրան Կոլումբիայի և Պերուի միջև և Ցիսպլատինյան պատերազմը (Բրազիլական կայսրության և Միացյալ Ռիվեր Փլեյթ Նահանգների միջև) փակուղով ավարտվեցին, չնայած վերջինս հանգեցրեց Ուրուգվայի անկախությանը (1828): Մի քանի տարի անց՝ 1831 թվականին Մեծ Կոլումբիայի փլուզումից հետո, ուժերի հավասարակշռությունը փոխվեց հօգուտ նորաստեղծ Պերու-Բոլիվիայի Համադաշնության (1836-1839): Այնուամենայնիվ, իշխանության այս կառուցվածքը ժամանակավոր եղավ՝ կապված Բոլիվիայի հետ համադաշնային պատերազմում (1836-1839) Հարավային Պերուի պետության նկատմամբ Հյուսիսային Պերուական պետության հաղթանակի և Գուերա Գրանդեում Արգենտինայի Համադաշնության պարտության արդյունքում (1839-1852):

Ավելի ուշ Հարավամերիկյան ազգերի միջև հակամարտությունները շարունակում էին որոշել նրանց սահմանները և տերության կարգավիճակը: Խաղաղ օվկիանոսի ափին Չիլին և Պերուն շարունակում էին ցույց տալ իրենց աճող գերակայությունը՝ հաղթելով Իսպանիային Չինչա կղզիների համար պատերազմում: Վերջապես, Խաղաղ օվկիանոսի պատերազմի ընթացքում Պերուի անվստահ պարտությունից հետո (1879-1883) Չիլին դարձավ գերիշխող տերություն Հարավային Ամերիկայի Խաղաղ օվկիանոսի ափին: Ատլանտյան ափին Պարագվայը փորձեց ավելի գերիշխող կարգավիճակ ձեռք բերել տարածաշրջանում, բայց Արգենտինայի, Բրազիլիայի և Ուրուգվայի միությունը (1864-1870 թվականների Եռակի դաշինքի պատերազմի արդյունքում) վերջ դրեց Պարագվայի հավակնություններին: Դրանից հետո Հարավային կոնի երկրները ՝ Արգենտինան, Բրազիլիան և Չիլին, մտան 20-րդ դար ՝ որպես ամենամեծ մայրցամաքային տերություններ:

Մի քանի երկրներ անկախություն ձեռք բերեցին միայն 20-րդ դարում:

- Պանամա, Կոլումբիայից, 1903 թվականին

- Տրինիդադ և Տոբագո, Մեծ Բրիտանիայից, 1962 թվականին

- Գայանա, Մեծ Բրիտանիայից, 1966 թվականին

- Սուրինամ, Հոլանդիայից, 1975 թվականին

Ֆրանսիական Գվիանան մնում է Ֆրանսիայի անդրծովյան դեպարտամենտը ։

20-րդ դար[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

1900–1920[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

By the start of the century, the United States continued its interventionist attitude, which aimed to directly defend its interests in the region. This was officially articulated in Theodore Roosevelt's Big Stick Doctrine, which modified the old Monroe Doctrine, which had simply aimed to deter European intervention in the hemisphere.

1930–1960[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The Great Depression posed a challenge to the region. The collapse of the world economy meant that the demand for raw materials drastically declined, undermining many of the economies of South America.

Intellectuals and government leaders in South America turned their backs on the older economic policies and turned toward import substitution industrialization. The goal was to create self-sufficient economies, which would have their own industrial sectors and large middle classes and which would be immune to the ups and downs of the global economy. Despite the potential threats to United States commercial interests, the Roosevelt administration (1933–1945) understood that the United States could not wholly oppose import substitution. Roosevelt implemented a good neighbor policy and allowed the nationalization of some American companies in South America. The Second World War also brought the United States and most Latin American nations together.

The history of South America during World War II is important because of the significant economic, political, and military changes that occurred throughout much of the region as a result of the war. In order to better protect the Panama Canal, combat Axis influence, and optimize the production of goods for the war effort, the United States through Lend-Lease and similar programs greatly expanded its interests in Latin America, resulting in large-scale modernization and a major economic boost for the countries that participated.[57]

Strategically, Brazil was of great importance because of its having the closest point in the Americas to Africa where the Allies were actively engaged in fighting the Germans and Italians. For the Axis, the Southern Cone nations of Argentina and Chile were where they found most of their South American support, and they utilised it to the fullest by interfering with internal affairs, conducting espionage, and distributing propaganda.[57][58][59]

Brazil was the only country to send an Expeditionary force to the European theatre; however, several countries had skirmishes with German U-boats and cruisers in the Caribbean and South Atlantic. Mexico sent a fighter squadron of 300 volunteers to the Pacific, the Escuadrón 201 were known as the Aztec Eagles (Aguilas Aztecas).

The Brazilian active participation on the battle field in Europe was divined after the Casablanca Conference. The President of the U.S., Franklin D. Roosevelt on his way back from Morocco met the President of Brazil, Getulio Vargas, in Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, this meeting is known as the Potenji River Conference, and defined the creation of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force.

Economics[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

According to author Thomas M. Leonard, World War II had a major impact on Latin American economies. Following the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, most of Latin America either severed relations with the Axis powers or declared war on them. As a result, many nations (including all of Central America, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Argentina, and Venezuela) suddenly found that they were now dependent on the United States for trade. The United States' high demand for particular products and commodities during the war further distorted trade. For example, the United States wanted all of the platinum produced in Colombia, all the silver of Chile, and all of cotton, gold and copper of Peru. The parties agreed upon set prices, often with a high premium, but the various nations lost their ability to bargain and trade in the open market.

Cold War[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Wars became less frequent in the 20th century, with Bolivia-Paraguay and Peru-Ecuador fighting the last inter-state wars. Early in the 20th century, the three wealthiest South American countries engaged in a vastly expensive naval arms race which was catalyzed by the introduction of a new warship type, the "dreadnought". At one point, the Argentine government was spending a fifth of its entire yearly budget for just two dreadnoughts, a price that did not include later in-service costs, which for the Brazilian dreadnoughts was sixty percent of the initial purchase.[60][61]

The continent became a battlefield of the Cold War in the late 20th century. Some democratically elected governments of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay were overthrown or displaced by military dictatorships in the 1960s and 1970s. To curtail opposition, their governments detained tens of thousands of political prisoners, many of whom were tortured and/or killed on inter-state collaboration. Economically, they began a transition to neoliberal economic policies. They placed their own actions within the US Cold War doctrine of "National Security" against internal subversion. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Peru suffered from an internal conflict. South America, like many other continents, became a battlefield for the superpowers during the Cold War in the late 20th century. In the postwar period, the expansion of communism became the greatest political issue for both the United States and governments in the region. The start of the Cold War forced governments to choose between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Late 20th century military regimes and revolutions[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

By the 1970s, leftists had acquired a significant political influence which prompted the right-wing, ecclesiastical authorities and a large portion of each individual country's upper class to support coups d'état to avoid what they perceived as a communist threat. This was further fueled by Cuban and United States intervention which led to a political polarisation. Most South American countries were in some periods ruled by military dictatorships that were supported by the United States of America.

Also around the 1970s, the regimes of the Southern Cone collaborated in Operation Condor killing many leftist dissidents, including some urban guerrillas.[62] However, by the early 1990s all countries had restored their democracies.

Colombia has had an ongoing, though diminished internal conflict, which started in 1964 with the creation of Marxist guerrillas (FARC-EP) and then involved several illegal armed groups of leftist-leaning ideology as well as the private armies of powerful drug lords. Many of these are now defunct, and only a small portion of the ELN remains, along with the stronger, though also greatly reduced FARC. These leftist groups smuggle narcotics out of Colombia to fund their operations, while also using kidnapping, bombings, land mines and assassinations as weapons against both elected and non-elected citizens.

Revolutionary movements and right-wing military dictatorships became common after World War II, but since the 1980s, a wave of democratisation came through the continent, and democratic rule is widespread now.[63] Nonetheless, allegations of corruption are still very common, and several countries have developed crises which have forced the resignation of their governments, although, in most occasions, regular civilian succession has continued.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the governments of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay were overthrown or displaced by U.S.-aligned military dictatorships. These detained tens of thousands of political prisoners, many of whom were tortured and/or killed (on inter-state collaboration, see Operation Condor). Economically, they began a transition to neoliberal economic policies. They placed their own actions within the U.S. Cold War doctrine of "National Security" against internal subversion. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Peru suffered from an internal conflict (see Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement and Shining Path). Revolutionary movements and right-wing military dictatorships have been common, but starting in the 1980s a wave of democratization came through the continent, and democratic rule is now widespread. Allegations of corruption remain common, and several nations have seen crises which have forced the resignation of their presidents, although normal civilian succession has continued. International indebtedness became a recurrent problem, with examples like the 1980s debt crisis, the mid-1990s Mexican peso crisis and Argentina's 2001 default.

Washington Consensus[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The set of specific economic policy prescriptions that were considered the "standard" reform package were promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, DC-based institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and the US Treasury Department during the 1980s and '90s.

21st century[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

A turn to the left[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

According to the BBC, a "common element of the 'pink tide' is a clean break with what was known at the outset of the 1990s as the 'Washington consensus', the mixture of open markets and privatisation pushed by the United States".[64] According to Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a pink tide president herself, Hugo Chávez of Venezuela (inaugurated 1999), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil (inaugurated 2003) and Evo Morales of Bolivia (inaugurated 2006) were "the three musketeers" of the left in South America.[65] By 2005, the BBC reported that out of 350 million people in South America, three out of four of them lived in countries ruled by "left-leaning presidents" elected during the preceding six years.[64]

Despite the presence of a number of Latin American governments which profess to embrace a leftist ideology, it is difficult to categorize Latin American states "according to dominant political tendencies, like a red-blue post-electoral map of the United States."[66] According to the Institute for Policy Studies, a liberal non-profit think-tank based in Washington, D.C.: "a deeper analysis of elections in Ecuador, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Mexico indicates that the "pink tide" interpretation—that a diluted trend leftward is sweeping the continent—may be insufficient to understand the complexity of what's really taking place in each country and the region as a whole".[66]

While this political shift is difficult to quantify, its effects are widely noticed. According to the Institute for Policy Studies, 2006 meetings of the South American Summit of Nations and the Social Forum for the Integration of Peoples demonstrated that certain discussions that "used to take place on the margins of the dominant discourse of neoliberalism, (have) now moved to the centre of public debate."[66]

Pink tide[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The term 'pink tide' (իսպ.՝ marea rosa, պորտ.՝ onda rosa) or 'turn to the Left' (Sp.: vuelta hacia la izquierda, Pt.: Guinada à Esquerda) are phrases which are used in contemporary 21st century political analysis in the media and elsewhere to describe the perception that leftist ideology in general, and left-wing politics in particular, were increasingly becoming influential in Latin America.[64][67][68]

Since the 2000s or 1990s in some countries, left-wing political parties have risen to power. Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, Fernando Lugo in Paraguay, Néstor and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in Argentina, Tabaré Vázquez and José Mujica in Uruguay, the Lagos and Bachelet governments in Chile, Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Rafael Correa of Ecuador are all part of this wave of left-wing politicians who also often declare themselves socialists, Latin Americanists or anti-imperialists.

- The list of leftist South American presidents is, by date of election, the following

- 1998: {{{2}}} Hugo Chávez, Venezuela[69]

- 1999: {{{2}}} Ricardo Lagos, Chile[70][71]

- 2002: {{{2}}} Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil[72][73][74][75]

- 2002: {{{2}}} Lucio Gutiérrez, Ecuador[76][77]

- 2003: {{{2}}} Néstor Kirchner, Argentina[78][79][80]

- 2004: {{{2}}} Tabaré Vázquez, Uruguay[81][82][83]

- 2005: {{{2}}} Evo Morales, Bolivia[84][Ն 1][93]

- 2006: {{{2}}} Michelle Bachelet, Chile[94][95]

- 2006: {{{2}}} Rafael Correa, Ecuador[96][97][98][99]

- 2007: {{{2}}} Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Argentina[100][101][note 1][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111]

- 2008: {{{2}}} Fernando Lugo, Paraguay[112][113]

- 2010: {{{2}}} José Mujica, Uruguay[114][115][116][117]

- 2010: {{{2}}} Dilma Rousseff, Brazil[118][119][120]

- 2011: {{{2}}} Ollanta Humala, Peru[121][122][123][124][125]

- 2013: {{{2}}} Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela[126][127][128][129]

- 2014: {{{2}}} Michelle Bachelet, Chile [130]

- 2015: {{{2}}} Tabaré Vázquez, Uruguay [131]

- 2017: {{{2}}} Lenín Moreno, Ecuador[132]

- 2019: {{{2}}} Alberto Fernández, Argentina

- 2020: {{{2}}} Luis Arce, Bolivia

- 2021: {{{2}}} Pedro Castillo, Peru[133]

- 2022: {{{2}}} Gabriel Boric Font, Chile [134]

- 2022: {{{2}}} Gustavo Petro, Colombia [135]

- 2023: {{{2}}} Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil [136]

Politics[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Կաղապար:Update section During the first decade of the 21st century, South American governments move to the political left, with leftist leaders being elected in Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela. Most South American countries are making an increasing use of protectionist policies, undermining a greater global integration but helping local development.

In 2008, the Union of South American Nations (USAN) was founded, which aimed to merge the two existing customs unions, Mercosur and the Andean Community, thus forming the third-largest trade bloc in the world.[137] The organization is planning for political integration in the European Union style, seeking to establish free movement of people, economic development, a common defense policy and the elimination of tariffs.[փա՞ստ] According to Noam Chomsky, USAN represents that "for the first time since the European conquest, Latin America began to move towards integration".[138][139][140][141][142][143][144][145]

Կաղապար:South America government from 1990

Most recent heads of state in South America[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- 2010: {{{2}}} Dilma Rousseff, Brazil[118][119][120]

- 2010: {{{2}}} José Mujica, Uruguay [146]

- 2010: {{{2}}} Sebastián Piñera, Chile [147]

- 2010: {{{2}}} Juan Manuel Santos[148]

- 2011: {{{2}}} Ollanta Humala, Peru[121][122][123][124][125]

- 2013: {{{2}}} Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela[126][127][128][129]

- 2013: {{{2}}} Horacio Cartés, Paraguay [149]

- 2014: {{{2}}} Michelle Bachelet, Chile [150]

- 2015: {{{2}}} Mauricio Macri, Argentina [151]

- 2015: {{{2}}} Tabaré Vázquez, Uruguay [152]

- 2015: {{{2}}} David Granger, Guyana [153]

- 2016: {{{2}}} Michel Temer, Brazil [154]

- 2016: {{{2}}} Pedro Pablo Kuczynski Godard, Peru

- 2017: {{{2}}} Lenín Moreno, Ecuador[132]

- 2018: {{{2}}} Sebastián Piñera, Chile [155]

- 2018: {{{2}}} Iván Duque Márquez, Colombia [156]

- 2018: {{{2}}} Martín Vizcarra, Peru [157]

- 2018: {{{2}}} Mario Abdo, Paraguay [158]

- 2019: {{{2}}} Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil [159]

- 2019: {{{2}}} Alberto Fernández, Argentina [160]

- 2020: {{{2}}} Luis Lacalle, Uruguay [161]

- 2020: {{{2}}} Luis Arce, Bolivia [162]

- 2020: {{{2}}} Manuel Merino de Lama, Peru [163]

- 2020: {{{2}}} Chandrikapersad "Chan" Santokhi, Suriname [164]

- 2020: {{{2}}} Irfaan Ali, Guyana [165]

- 2020: {{{2}}} Francisco Sagasti, Peru [166]

- 2021: {{{2}}} Guillermo Lasso, Ecuador[167]

- 2021: {{{2}}} Pedro Castillo, Peru[133]

- 2022: {{{2}}} Gabriel Boric Font, Chile [134]

- 2022: {{{2}}} Gustavo Petro, Colombia [135]

- 2022: {{{2}}} Dina Boluarte, Peru [168]

- 2023: {{{2}}} Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil [169]

- 2023: {{{2}}} Santiago Peña, Paraguay [170]

- 2023: {{{2}}} Daniel Noboa, Ecuador[171]

- 2023: {{{2}}} Javier Milei, Argentina [172]

See also[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- Inca Empire

- Gran Colombia

- History of Latin America

- Military history of South America

- Peru–Bolivian Confederation

- Simón Bolívar

- José de San Martín

- Francisco Pizarro

Notes[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ongoing Kiphu research suggests that the Inca used a phonetic system as a form of writing in the kiphu. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/journals/ca/pr/170419

References[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- ↑ Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs : America's First Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson. էջեր 9–25. ISBN 0-500-28503-9.

- ↑ Haas, Jonathan; Winifred Creamer; Alvaro Ruiz (23 December 2004). «Dating the Late Archaic occupation of the Norte Chico region in Peru». Nature. 432 (7020): 1020–1023. Bibcode:2004Natur.432.1020H. doi:10.1038/nature03146. PMID 15616561. S2CID 4426545.

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 3,2 3,3 3,4 3,5 Marshall, Larry (July–August 1988). «Land Mammals and the Great American Interchange». American Scientist. 76 (4): 380–388. Bibcode:1988AmSci..76..380M.

- ↑ «Dinosaur-killing asteroid strike gave rise to Amazon rainforest». BBC News. 2 April 2021. Վերցված է 9 May 2021-ին.

- ↑ Carvalho, Mónica R.; Jaramillo, Carlos; Parra, Felipe de la; Caballero-Rodríguez, Dayenari; Herrera, Fabiany; Wing, Scott; Turner, Benjamin L.; D'Apolito, Carlos; Romero-Báez, Millerlandy; Narváez, Paula; Martínez, Camila; Gutierrez, Mauricio; Labandeira, Conrad; Bayona, German; Rueda, Milton; Paez-Reyes, Manuel; Cárdenas, Dairon; Duque, Álvaro; Crowley, James L.; Santos, Carlos; Silvestro, Daniele (2 April 2021). «Extinction at the end-Cretaceous and the origin of modern Neotropical rainforests». Science (անգլերեն). 372 (6537): 63–68. Bibcode:2021Sci...372...63C. doi:10.1126/science.abf1969. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33795451. S2CID 232484243. Վերցված է 9 May 2021-ին.

- ↑ «Native Americans migrated to the New World in three waves, Harvard-led DNA analysis shows | Boston.com». www.boston.com.

- ↑ Pino, Mario; Dillehay, Tom D. (June 2023). «Monte Verde II: an assessment of new radiocarbon dates and their sedimentological context». Antiquity (անգլերեն). 97 (393): 524–540. doi:10.15184/aqy.2023.32. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ↑ Prates, Luciano; Perez, S. Ivan (2021-04-12). «Late Pleistocene South American megafaunal extinctions associated with rise of Fishtail points and human population». Nature Communications (անգլերեն). 12 (1): 2175. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22506-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8041891. PMID 33846353.

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 9,2 9,3 O'Brien, Patrick. (General Editor). Oxford Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. p. 25

- ↑ Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: Norton, 1999, p. 100

- ↑ Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: Norton, 1999 (pp. 126–27)

- ↑ Howe, Kerry R., The Quest for Origins, Penguin Books, 2003, 0-14-301857-4, pp. 81, 129

- ↑ Solis, Ruth Shady; Haas, Jonathan; Creamer, Winifred (April 27, 2001). «Dating Caral, a Preceramic Site in the Supe Valley on the Central Coast of Peru». Science. 292 (5517): 723–726. Bibcode:2001Sci...292..723S. doi:10.1126/science.1059519. PMID 11326098. S2CID 10172918 – via science.sciencemag.org.

- ↑ «Oldest evidence of city life in the Americas reported in Science, early urban planners emerge as power players». EurekAlert!. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2017-12-13-ին. Վերցված է 2016-03-22-ին.

- ↑ «Historia» (իսպաներեն). Fundación Municipal "Turismo Para Cuenca". Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 17 May 2015-ին. Վերցված է 13 August 2015-ին.

- ↑ «The Cañari of Ecuador, a 'palace' and a pig». August 12, 2014.

- ↑ «Glottolog 2.7 – Core Chibchan». glottolog.org.

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, p.26

- ↑ (es) Muysca – Muysccubun Dictionary Online

- ↑ «Official website Tenza». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից June 2, 2015-ին.

- ↑ Kruschek, 2003

- ↑ Gamboa Mendoza, 2016

- ↑ Although sources state "47,000", this cannot be correct as that would be whole Boyacá and Cundinamarca and include Panche, Lache and Muzo

- ↑ (es) Muisca Confederation area almost 47,000 km2, page 12

- ↑ Palacios, Marco; Safford, Frank (March 22, 2002). Colombia: país fragmentado, sociedad dividida: su historia. Grupo Editorial Norma. ISBN 9789580465096 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Groot, 2014

- ↑ 27,0 27,1 Daza, 2013, p. 23

- ↑ Francis, 1993, p. 44

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, p. 207

- ↑ García, 2012, p. 43

- ↑ Daza, 2013, p. 26

- ↑ (es) Biography Tisquesusa – Pueblos Originarios

- ↑ Simon Romero (January 14, 2012). «Once Hidden by Forest, Carvings in Land Attest to Amazon's Lost World». The New York Times.

- ↑ 34,0 34,1 «Unnatural Histories – Amazon». BBC Four.

- ↑ Smith, A (1994). Explorers of the Amazon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-76337-8.

- ↑ 36,0 36,1 Chris C. Park (2003). Tropical Rainforests. Routledge. էջ 108. ISBN 9780415062398.

- ↑ The influence of human alteration has been generally underestimated, reports Darna L. Dufour: "Much of what has been considered natural forest in Amazonia is probably the result of hundreds of years of human use and management." "Use of Tropical Rainforests by Native Amazonians", BioScience 40, no. 9 (October 1990):658. For an example of how such peoples integrated planting into their nomadic lifestyles, see Rival, Laura, 1993. "The Growth of Family Trees: Understanding Huaorani Perceptions of the Forest", Man 28(4):635–652.

- ↑ Heckenberger, M.J.; Kuikuro, A; Kuikuro, UT; Russell, JC; Schmidt, M; Fausto, C; Franchetto, B (19 September 2003), «Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland?», Science (published 2003), vol. 301, no. 5640, էջեր 1710–1714, Bibcode:2003Sci...301.1710H, doi:10.1126/science.1086112, PMID 14500979, S2CID 7962308

- ↑ «Chavín de Huántar Information». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2018-01-11-ին. Վերցված է 2018-01-13-ին.

- ↑ «Chavin Civilization». World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ «Moche Civilization». World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ «Rich Tombs from Moche Culture Uncovered on Peruvian Coast | UCLA». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2018-01-15-ին. Վերցված է 2018-01-14-ին.

- ↑ «Moche | ancient South American culture». Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Bourget, Steve (2010-06-28). Sex, Death, and Sacrifice in Moche Religion and Visual Culture. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292783188.

- ↑ «quipu: Incan counting tool». Encyclopædia Britannica (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2017-10-13-ին.

- ↑ 46,0 46,1 46,2 46,3 Wunder, Sven (2003), Oil Wealth and the Fate of the Forest: A Comparative Study of Eight Tropical Countries, Routledge. p. 130, 0-203-98667-9.

- ↑ This is disputed by modern Caribs.

- ↑ Butzer, Karl W. (1992). «The Americas before and after 1492: An Introduction to Current Geographical Research». Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 347. ISSN 0004-5608. JSTOR 2563350.

- ↑ Rutherford, Adam (2017-10-03). «A New History of the First Peoples in the Americas». The Atlantic (ամերիկյան անգլերեն). Վերցված է 2020-02-21-ին.

- ↑ Cook, Noble David. Born To Die, p. 13.

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. էջ 163. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ↑ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2010-05-01). «The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas». Journal of Economic Perspectives (անգլերեն). 24 (2): 163–188, 181. doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ↑ Cartwright, Mark. «The Gold of the Conquistadors». World History Encyclopedia (անգլերեն). Վերցված է 26 October 2022-ին.

- ↑ Robertson, Ian A. (December 1977). «Dutch creole languages in Guayana». Boletín de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe. 23 (23): 61–67. JSTOR 25674996.

- ↑ «Berbice Uprising in 1763». Slavenhandel MCC (Provincial Archives of Zeeland). Վերցված է 7 August 2020-ին.

- ↑ Hoonhout, Bram; Mareite, Thomas (2019-01-02). «Freedom at the fringes? Slave flight and empire-building in the early modern Spanish borderlands of Essequibo–Venezuela and Louisiana–Texas». Slavery & Abolition. 40 (1): 61–86. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2018.1447806. hdl:1887/60431. ISSN 0144-039X. S2CID 148984945.

- ↑ 57,0 57,1 Leonard, Thomas M.; John F. Bratzel (2007). Latin America during World War II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-3741-5.

- ↑ «Cryptologic Aspects of German Intelligence Activities in South America during World War II» (PDF). David P. Mowry. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից (PDF) 2013-09-18-ին. Վերցված է August 9, 2013-ին.

- ↑ Richard Hough, The Big Battleship (London: Michael Joseph, 1966), 19. Կաղապար:Oclc.

- ↑ Robert Scheina, Latin America: A Naval History, 1810–1987 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987), 86. 0-87021-295-8. Կաղապար:Oclc.

- ↑ Victor Flores Olea. «Editoriales – El Universal – 10 de abril 2006: Operacion Condor» (իսպաներեն). El Universal (Mexico). Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2007-06-28-ին. Վերցված է 2009-03-24-ին.

- ↑ "The Cambridge History of Latin America", edited by Leslie Bethell, Cambridge University Press (1995) 0-521-39525-9

- ↑ 64,0 64,1 64,2 BBC News Americas (2 March 2005). «South America's leftward sweep». bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Noel, Andrea (29 December 2015). «The Year the 'Pink Tide' Turned: Latin America in 2015». VICE News (ամերիկյան անգլերեն). Վերցված է 30 December 2015-ին.

- ↑ 66,0 66,1 66,2 «Foreign Policy in Focus | Latin America's Pink Tide?». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից September 10, 2009-ին. Վերցված է March 24, 2016-ին. Institute for Policy Studies: Latin America's Pink Tide?

- ↑ «Arquivo.pt». arquivo.pt. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2016-05-16-ին. Վերցված է 2016-03-24-ին.

- ↑ «The many stripes of anti-Americanism – The Boston Globe». boston.com.

- ↑ McCoy, Jennifer L; Myers, David J. (2006). The Unraveling of Representative Democracy in Venezuela. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. էջ 310. ISBN 978-0-8018-8428-3.

- ↑ Góngora, Álvaro; de la Taille, Alexandrine; Vial, Gonzalo. Jaime Eyzaguirre en su tiempo (իսպաներեն). Zig-Zag. էջեր 173–174.

- ↑ «Watson Institute for International Studies». Brown University. 2009. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից August 18, 2009-ին. Վերցված է 2009-09-14-ին.

- ↑ «Lula leaves office as Brazil's 'most popular' president». BBC. 31 December 2010. Վերցված է 4 January 2011-ին.

- ↑ «The Most Popular Politician on Earth». Newsweek. 31 December 2010. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 29 December 2010-ին. Վերցված է 4 January 2011-ին.

- ↑ «Lula's last lap». The Economist. 8 January 2009. Վերցված է 4 January 2011-ին.

- ↑ Throssell, Elizabeth 'Liz' (30 September 2010). «Lula's legacy for Brazil's next president». BBC News. Վերցված է 29 March 2012-ին.

- ↑ «Ecuador lifts state of emergency». BBC News. April 17, 2005. Վերցված է May 11, 2010-ին.

- ↑ «Perfil de Lucio Gutiérrez». hoy.com.ec (իսպաներեն). Explored. November 25, 2002. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից August 3, 2013-ին. Վերցված է September 19, 2013-ին.

- ↑ «Elections in Argentina: Cristina's Low-Income Voter Support Base». Upsidedownworld.org. 24 October 2007.

- ↑ «Latin American Program». Wilson Center. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2009-01-01-ին. Վերցված է 2016-03-22-ին.

- ↑ «Archived copy» (PDF). Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից (PDF) June 24, 2010-ին. Վերցված է October 30, 2011-ին.

{{cite web}}: CS1 սպաս․ արխիվը պատճենվել է որպես վերնագիր (link) - ↑ «Social democracy lives in Latin America». Project Syndicate. 10 August 2009.

- ↑ Verónica Amarante and Andrea Vigorito (August 2012). «The Expansion of Non-Contributory Transfers in Uruguay in Recent Years» (PDF). International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից (PDF) 2016-04-04-ին. Վերցված է 2016-03-22-ին.

- ↑ «Uruguay: A Chance to Leave Poverty Behind». IPS News. 3 September 2009. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից November 7, 2009-ին.

- ↑ Harten 2011, p. 35; Webber 2011, p. 62.

- ↑ Muñoz-Pogossian, 2008, էջ 180

- ↑ Webber, 2011, էջ 1

- ↑ Philip, Panizza, էջ 57

- ↑ Farthing, Kohl, էջ 1

- ↑ «Profile: Bolivia's President Evo Morales». BBC News. 13 October 2014.

- ↑ 90,0 90,1 90,2 Harten, 2011, էջ 7

- ↑ Farthing, Kohl, էջ 22

- ↑ Sivak 2010, p. 82–83; Harten 2011, pp. 112–118; Farthing & Kohl 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ Carroll, Rory (7 December 2009). «Evo Morales wins landslide victory in Bolivian presidential elections». The Guardian. London. Վերցված է 20 August 2011-ին.

- ↑ «Michelle Bachelet: primera mujer presidenta y primer presidente reelecto desde 1932». www.facebook.com/RadioBioBio. 16 December 2013. Վերցված է 11 March 2016-ին.

- ↑ «Bachelet critica a la derecha por descalificarla por ser agnóstica» [Bachelet criticises the political right for discounting her because of her agnosticism]. El Mercurio (իսպաներեն). 30 December 2005. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 25 December 2014-ին. Վերցված է 25 November 2014-ին.

- ↑ "Avenger against oligarchy" wins in Ecuador The Real News, 27 April 2009.

- ↑ Soto, Alonso (14 April 2007). «Ecuador's Correa admits father was drug smuggler». Reuters UK. Վերցված է 14 Apr 2007-ին.

- ↑ Guy Hedgecoe (29 April 2009). «Rafael Correa: An Ecuadorian Journey». openDemocracy. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 4 March 2016-ին. Վերցված է 22 March 2016-ին.

- ↑ «Rafael Correa Icaza». GeneAll.net. 23 March 1934. Վերցված է 4 December 2011-ին.

- ↑ «CFK back at Olivos presidential residency after CELAC summit». Buenos Aires Herald. 29 January 2014. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2 February 2014-ին.

- ↑ 101,0 101,1 «CFK to Harvard students: there is no 'dollar clamp'; don't repeat monochord questions». MercoPress. 28 September 2012.

- ↑ 102,0 102,1 «Profile: Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner». BBC News. 8 October 2013.

- ↑ «Aerolineas takeover shadows Cristina K visit to Spain». MercoPress. 9 February 2009. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 28 June 2014-ին.

- ↑ «Latin America's crony capitalism. (Alvaro Vargas Llosa)(Interview)». Reason. 28 January 2013.(չաշխատող հղում)

- ↑ Roberts, James M. (22 April 2010). «Cronyism and Corruption are Killing Economic Freedom in Argentina». Heritage Foundation. HighBeam Research. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 14 May 2013-ին.

- ↑ Barbieri, Pierpaolo (8 August 2012). «Pierpaolo Barbieri: A Lesson in Crony Capitalism». WSJ.

- ↑ «Don't lie to me, Argentina». The Economist. 25 February 2012. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 7 March 2013-ին.

- ↑ «The price of cooking the books». The Economist. 25 February 2012. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 14 February 2013-ին.

- ↑ «Knock, knock». The Economist. 21 June 2012. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 5 March 2013-ին.

- ↑ «El Gobierno usó a Fútbol para Todos para atacar a Macri». Clarín. August 11, 2012.

- ↑ «El Gobierno difundió un aviso polémico aviso sobre el subte». La Nación. August 11, 2012. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից January 10, 2016-ին. Վերցված է March 22, 2016-ին.

- ↑ Orsi, Peter (2012-06-24). «Does Paraguay risk pariah status with president's ouster?». Associated Press.

- ↑ «Frente Guasu». frenteguasu.org.py. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից May 3, 2013-ին.

- ↑ Hernandez, Vladimir (14 November 2012). «Jose Mujica: The World's 'Poorest' President». BBC News Magazine.

- ↑ Jonathan Watts (13 December 2013). Uruguay's president José Mujica: no palace, no motorcade, no frills. The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Mujica paseará por Muxika, la tierra de sus antepasados Արխիվացված 2016-03-28 Wayback Machine, Diario La República

- ↑ Mujica recibió las llaves de la ciudad de Muxika Արխիվացված 2016-03-28 Wayback Machine, Diario La República

- ↑ 118,0 118,1 EFE. "Dilma, 1ª mulher presidente e única economista em 121 anos de República". BOL. 31 October 2010.

- ↑ 119,0 119,1 Bennett, Allen "Dilma Rousseff biography" (չաշխատող հղում) , Agência Brasil, 9 August 2010

- ↑ 120,0 120,1 Daniel Schwartz (31 October 2010). «Dilma Rousseff». CBC News CBC.ca. Վերցված է 27 October 2014-ին.

- ↑ 121,0 121,1 The Guardian, April 11, 2011, Peru elections: Fujimori and Humala set for runoff vote

- ↑ 122,0 122,1 Leahy, Joe. «Peru president rejects link to Petrobras scandal». FT.com. Financial Times. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 2022-12-10-ին. Վերցված է 24 February 2016-ին.

- ↑ 123,0 123,1 Post, Colin (23 February 2016). «Peru: Ollanta Humala implicated in Brazil's Carwash scandal». www.perureports.com. Վերցված է 23 February 2016-ին.

- ↑ 124,0 124,1 Diario Hoy, October 31, 2000, PERU, CORONELAZO NO CUAJA

- ↑ 125,0 125,1 (es) BBC, January 4, 2005, Perú: insurgentes se rinden

- ↑ 126,0 126,1 "Nicolas Maduro sworn in as new Venezuelan president". BBC News. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013

- ↑ 127,0 127,1 «Perfil | ¿Quién es Nicolás Maduro?». El Mundo (իսպաներեն). 27 December 2012. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2 October 2013-ին. Վերցված է 9 March 2013-ին.

- ↑ 128,0 128,1 «Profile: Nicolas Maduro – Americas». Al Jazeera English. March 2013. Վերցված է 9 March 2013-ին.

- ↑ 129,0 129,1 Lopez, Virginia; Watts, Jonathan (15 April 2013). «Who is Nicolás Maduro? Profile of Venezuela's new president». The Guardian. Վերցված է 27 March 2015-ին.

- ↑ «Ex-president Michelle Bachelet wins Chile poll run-off». BBC News. 15 December 2013.

- ↑ «Tabare Vazquez wins Uruguay's run-off election». BBC News. 30 November 2014.

- ↑ 132,0 132,1 Santiago Piedra Silva (2017-05-24). «New leftist Ecuador president takes office». Yahoo.com. Վերցված է 2017-07-16-ին.

- ↑ 133,0 133,1 «Peru: Pedro Castillo sworn in as president». Deutsche Welle. 28 July 2021.

- ↑ 134,0 134,1 «Gabriel Boric, 36, sworn in as president to herald new era for Chile». the Guardian (անգլերեն). 11 March 2022.

- ↑ 135,0 135,1 «Ex-rebel takes oath as Colombia's first left-wing president». www.aljazeera.com (անգլերեն).

- ↑ «Lula sworn in as Brazil president as predecessor Bolsonaro flies to US». BBC News. 1 January 2023.

- ↑ «Globalpolicy.org». Globalpolicy.org. 2008-10-29. Վերցված է 2010-10-24-ին.

- ↑ (pt) Giovana Sanchez. "Noam Chomsky critica os EUA e elogia o papel do Brasil na crise de Honduras". G1. September 30, 2009,

- ↑ The phrase has been used in the past for this same purpose. It has never been officially proposed or used. Collazo, Ariel B. La Federación de Estados: Única solución para el drama de América Latina. n/d, circa 1950–1960.

- ↑ Duhalde, Eduardo (13 July 2004). "Hacia los Estados Unidos de Sudamérica."(չաշխատող հղում) La Nación.

- ↑ Grorjovsky, Nestor (14 July 2004). "Duhalde señaló que el Mercosur es un paso para la Unión Sudamericana" Արխիվացված 2012-02-05 Wayback Machine Reconquista-Popular.

- ↑ Collazo, Ariel (15 July 2004). "Los Estados Unidos de Sudamérica" La República.

- ↑ 29 July 2004,interview Արխիվացված 5 Ապրիլ 2016 Wayback Machine with Mexican President Vicente Fox by Andrés Oppenheimer. Mexico:Presidencia de la República

- ↑ "Estados Unidos de Sudamérica" Արխիվացված 2015-01-03 Wayback Machine Herejías y silencios. (22 November 2005).

- ↑ Duhalde, Eduardo (6 December 2004). "Sudamérica y un viejo sueño." Արխիվացված 2008-10-13 Wayback Machine Clarín

- ↑ «Ex-rebel inaugurated in Uruguay». 1 March 2010.

- ↑ «Billionaire sworn in as Chilean president - CNN.com». www.cnn.com (անգլերեն). 11 March 2010.

- ↑ «New Colombian president sworn in». BBC News. 8 August 2010.

- ↑ «Ecuador did not attend the assumption of the President of Paraguay». Ecuador Times. 15 August 2013.

- ↑ «Michelle Bachelet sworn in as Chile's president». BBC News. 11 March 2014.

- ↑ «Argentine President Mauricio Macri sworn in». France 24 (անգլերեն). 10 December 2015.

- ↑ «Vazquez sworn in as Uruguay's president». France 24 (անգլերեն). 2 March 2015.

- ↑ «Granger sworn in as President». Stabroek News. 16 May 2015.

- ↑ «Temer officially sworn in as Brazilian president». euronews (անգլերեն). 31 August 2016.

- ↑ «Sebastian Piñera sworn in as Chile's president». www.efe.com (անգլերեն). 11 March 2018.

- ↑ «Iván Duque: Colombia's new president sworn into office». BBC News. 8 August 2018.

- ↑ «Martin Vizcarra sworn in as Peru's president». www.aljazeera.com (անգլերեն).

- ↑ «New Paraguayan President Abdo Benítez sworn in». BBC News. 15 August 2018.

- ↑ «Brazil's Jair Bolsonaro sworn in as new president». www.timesofisrael.com. 1 January 2019.

- ↑ Aires, Reuters in Buenos (10 December 2019). «'We're back': Alberto Fernández sworn in as Argentina shifts to the left». the Guardian (անգլերեն).

{{cite news}}:|first1=has generic name (օգնություն) - ↑ «Uruguay's new center-right president sworn in». France 24 (անգլերեն). 1 March 2020.

- ↑ «Luis Arce sworn in as Bolivia's president». www.aa.com.tr. 9 November 2020.

- ↑ Collyns, Dan (2020-11-10). «Peru's new president accused of coup after ousting of predecessor». The Guardian (բրիտանական անգլերեն). ISSN 0261-3077. Վերցված է 2023-12-29-ին.

- ↑ «Chan Santokhi sworn is as new president of Suriname». CARICOM. 16 July 2020. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 15 December 2021-ին. Վերցված է 15 December 2021-ին.

- ↑ «Guyana swears in Irfaan Ali as president after long stand-off». BBC News. 3 August 2020.

- ↑ «Peru's new president Sagasti sworn in – DW – 11/17/2020». dw.com (անգլերեն).

- ↑ «Conservative Guillermo Lasso sworn in as Ecuador's new president». The Río Times. 24 May 2021.

- ↑ «Peru's President Pedro Castillo replaced by Dina Boluarte after impeachment». BBC News. 7 December 2022.

- ↑ «Lula sworn in as Brazil president as predecessor Bolsonaro flies to US». BBC News. 1 January 2023.

- ↑ Desantis, Daniela; Elliott, Lucinda; Elliott, Lucinda (16 August 2023). «Paraguay's President Pena sworn in, Taiwan VP in attendance». Reuters (անգլերեն).

- ↑ «Business heir Daniel Noboa sworn in as Ecuador president». Al Jazeera (անգլերեն).

- ↑ «In inaugural speech, Argentina's Javier Milei prepares nation for painful shock adjustment». AP News (անգլերեն). 2023-12-10. Վերցված է 2023-12-18-ին.

Historiography[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- Deforestation. World Geography. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill/Glencoe, 2000. 202–204

- Farthing, Linda C.; Kohl, Benjamin H. (2014). Evo's Bolivia: Continuity and Change. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75868-1.

- Harten, Sven (2011). The Rise of Evo Morales and the MAS. London and New York: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84813-523-9.

- Hensel, Silke. "Was There an Age of Revolution in Latin America?: New Literature on Latin American Independence." Latin American Research Review (2003) 38#3 pp. 237–249. online

- Muñoz-Pogossian, Betilde (2008). Electoral Rules and the Transformation of Bolivian Politics: The Rise of Evo Morales. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-60819-1.

- Philip, George; Panizza, Francisco (2011). The Triumph of Politics: The Return of the Left in Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-4749-4.

- Sheil, D.; Wunder, S. (2002). «The value of tropical forest to local communities: complications, caveats, and cautions» (PDF). Conservation Ecology. 6 (2): 9. doi:10.5751/ES-00458-060209. hdl:10535/2768.

- Sivak, Martín (2010). Evo Morales: The Extraordinary Rise of the First Indigenous President of Bolivia. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-62305-7.

- Uribe, Victor M. "The Enigma of Latin American Independence: Analyses of the Last Ten Years," Latin American Research Review (1997) 32#1 pp. 236–255 in JSTOR

- Wade, Lizzie. (2015). "Drones and satellites spot lost civilizations in unlikely places." Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science),

- Webber, Jeffrey R. (2011). From Rebellion to Reform in Bolivia: Class Struggle, Indigenous Liberation, and the Politics of Evo Morales. Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-60846-106-6.

Bibliography[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Prehistory[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- Marshall, Larry G. (1988). «Land Mammals and the Great American Interchange» (PDF). American Scientist. 76 (4): 380–388. Bibcode:1988AmSci..76..380M. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից (PDF) 2016-08-27-ին. Վերցված է 2016-08-26-ին.

Muisca[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- Daza, Blanca Ysabel (2013). Historia del proceso de mestizaje alimentario entre Colombia y España – History of the integration process of foods between Colombia and Spain (PhD thesis) (իսպաներեն). Barcelona, Spain: Universitat de Barcelona.

- Francis, John Michael (1993). "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (Masters thesis). University of Alberta.

- Gamboa Mendoza, Jorge (2016). Los muiscas, grupos indígenas del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Una nueva propuesta sobre su organizacíon socio-política y su evolucíon en el siglo XVI – The Muisca, indigenous groups of the New Kingdom of Granada. A new proposal on their social-political organization and their evolution in the 16th century (իսպաներեն). Banrepcultural. Արխիվացված օրիգինալից 2019-11-03. Վերցված է 2016-07-08-ին – via YouTube.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 սպաս․ bot: original URL status unknown (link) - García, Jorge Luis (2012). The Foods and crops of the Muisca: a dietary reconstruction of the intermediate chiefdoms of Bogotá (Bacatá) and Tunja (Hunza), Colombia (PDF) (Masters thesis). University of Central Florida. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից (PDF) 2014-05-03-ին. Վերցված է 2016-07-08-ին.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María (2008). Sal y poder en el altiplano de Bogotá, 1537–1640 (իսպաներեն). Universidad Nacional de Colombia. ISBN 978-958-719-046-5.

- Kruschek, Michael H. (2003). The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Pittsburgh. Վերցված է 2016-07-08-ին.

- Ocampo López, Javier (2007). Grandes culturas indígenas de América – Great indigenous cultures of the Americas (իսպաներեն). Bogotá: Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A. ISBN 978-958-14-0368-4.

Further reading[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

| Վիքիպահեստ նախագծում կարող եք այս նյութի վերաբերյալ հավելյալ պատկերազարդում գտնել ArthurZQ/Ավազարկղ Բ կատեգորիայում։ |

- Harvey, Robert (2000). Liberators: Latin America's Struggle For Independence, 1810–1830. John Murray, London. ISBN 0-7195-5566-3.

Կաղապար:History of South America

Կաղապար:South America topics

Կաղապար:History by continent

Կաղապար:Americas topic

Քաղվածելու սխալ՝ <ref> tags exist for a group named "Ն", but no corresponding <references group="Ն"/> tag was found