Մասնակից:Աննե Յան/Ավազարկղ

- Գերնկճախտի հետ[1]։

- Գուրմանդի համախտանիշ. հազվադեպ վիճակ, որը հանդիպում է ճակատային բլթի վնասումից հետո՝ հանգեցնելով լավ սննդամթերքի վրա կպչուն սևեռման[2]։

Նշաններ և ախտանիշներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ախտանիշները և բարդությունները տատանվում են սնման խանգարման բնույթին և ծանրությանը համապատասխան[29]։

| ակնե | քսերոզ | ամենոռեա | ատամի կորուստ, խոռոչներ |

| կոնսպիրացիա | դիարեա | ջրի կուտակում և/կամ այտուց | լանուգո |

| telogen effluvium | սրտի կանգ | հիպոկալեմիա | մահ |

| օստեոպորոզ[3] | էլեկտրոլիտների անհավասարակշռություն | հիպոնատրեմիա | ուղեղի հետաճ[4][5] |

| պելլագրա[6] | ցինգա | երիկամային անբավարարություն | ինքնասպանություն[7][8][9] |

Սնման խանգարման ֆիզիկական ախտանիշներից են թուլությունը, հոգնածությունը, զգայունությունը ցրտի նկատմամբ, տղամարդկանց մոտ մորուքի աճի նվազումը, էրեկցիայի կրճատումը, լիբիդոյի իջեցումը, քաշի կորուստը և աճի խաթարումը[10]։ Ոչ բացատրված խռպոտությունը կարող է իր հիմքում գտնվող սնման խանգարման ախտանիշ լինել՝ որպես թթվային ռեֆլյուքսի կամ ստամոքսային թթվային զանգվածի` դեպի կոկորդակերակրափողային ուղի մուտքի հետևանք։ Հիվանդները, ովքեր ինքնահարուցում են փսխում, ինչպես օրինակ, անորեքսիայի գերսնման-դուրսբերման տեսակով կամ բուլիմիայի դուրսբերման տեսակով տառապողները ենթակա են թթվային ռեֆլյուքսի վտանգի։ Պոլիկիստոզ (բազմախոռոչային) ձվարանային համախտանիշը կանանց ախտահարող ամենատարածված խանգարումն է։ Թեպետ այն հաճախ կապված է գիրության հետ, սակայն կարող է ի հայտ գալ նաև բնականոն քաշ ունեցող անհատների մոտ։ Պոլիկիստոզ ձվարանային համախտանիշը կապված է գերսնման և բուլիմիկ վարքագծի հետ [11][12][13][14][15][16]։ Այլ հնարավոր դրսևորումներ են չոր շրթունքները[17], այրվող լեզուն[17], հարականջային գեղձի այտուցը[17] և քունքաստործնոտային խանգարումները[17]։

Պրո-անա ենթամշակույթ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Պրո-անա-ն վերաբերում է անորեքսիա սնման խանգարման հետ կապված վարքագծի առաջխաղացմանը։ Առանձին կայքեր նպաստում են սնման խանգարումներին և կարող են շփման հնարավորություններ տրամադրել անհատներին սնման խանգարումները պահպանելու համար: Այս կայքերի անդամները սովորաբար մտածում են, որ իրենց սնման խանգարումը քաոսային կյանքի միակ ոլորտն է, որն իրենք կարող են վերահսկել[18]։ Այս կայքերը հաճախ ինտերակտիվ են և ունեն քննարկման հարթակներ, որտեղ անհատները կարող են բաժնեկցել իրենց մարտավարությամբ, մտքերով և փորձառությամբ, ինչպիսիք են սննդակարգը և մարզման ծրագրերը, որոնք օգնում են հասնել ծայրահեղ ցածր քաշերի[19]։ Սնման խանգարումները խթանող անձնական վեբ-բլոգերը ապաքինման և կազդուրման վրա կենտրոնացած բլոգերի հետ համեմատող հետազոտությունը բացահայտել է, որ առաջինները բնութագրվում են ցածր ճանաչողական գործընթացին բնորոշ լեզվով, գործածում են ավելի փակ գրելաոճ, պարունակում են նվազ զգայական արտահայտչականություն և ավելի քիչ հասարակական հղումներ և ավելի շատ են կենտրոնացած սննդային բովանդակության վրա, քան ապաքինման բլոգերը[20]։

Հոգեախտաբանություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Սնման խանգարումների հոգեախտաբանությունը կենտրոնանում է այնպիսի հարցերի վրա, ինչպիսիք են մարմնակազմվածքի մասին մտահոգությունը (ինչպիսիք են մարմնի քաշը և ձևը), ինքնազգացողության կախյալությունը մարմնի քաշից և ձևից, մարմնի զանգվածի ավելացման վախը անգամ թերկշիռ լինելիս, ախտանիշների ծանրության հերքումը և մարմնի աղավաղման շարունակումը[10]։

Պատճառներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Սնման խանգարումների պատճառները հստակ չեն։

Սնման խանգարումներ ունեցող շատ մարդիկ ունեն նաև մարմնի ձևախախտման խանգարում, որի ժամանակ վերափոխվում է անձի ինքնաընկալումը[21][22]։ Հետազոտությունները հայտնաբերել են, որ մարմնի ձևախախտման համախտանիշ ունեցող անհատների զգալի մասն ունի սնման խանգարման այս կամ այն տեսակը ևս, ըստ որում նրանց15% տառապում է անորեքսիայով կամ բուլիմիայով[21]։ Մարմնի ձևախախտման համախտանիշի և անորեքսիայի միջև կապը բխում է այն փաստից, որ երկուսն էլ բնութագրվում են արտաքին տեսքի մասին արտահայտված մտահոգությամբ և մարմնակազմվածքի ընկալման խեղաթյուրմամբ[22]։ Կան նաև շատ այլ հավանական գործոններ, ինչպիսիք են շրջակա միջավայրի, հասարակական և միջանձնային գործոնները, որոնք կարող են խթանել հիվանդությունների զարգացումը և նպաստել վերջիններիս պահպանմանը[23]։ Սնման խանգարումների դեպքերի աճի մեջ հաճախ մեղադրվում են ԶԼՄ-ներն այն պատճառով, որ մոդելների և հայտնի մարդկանց իդեալականացված նիհար ֆիզիկական կերպարանքը դրդում է կամ անգամ ստիպում մարդկանց, որ իրենք էլ փորձեն հասնել նման արդյունքի։ ԶԼՄ-ները մեղադրվում են իրականության խեղաթյուրման մեջ այն իմաստով, որ նրանցում պատկերված մարդիկ կամ ի բնե նիհար են և հետևաբար նորմայի համար ներկայացուցչական չեն, կամ անբնական նիհար են՝ ստիպելով իրենց ունենալ իդեալական տեսք ի հաշիվ սեփական մարմնի նկատմամբ չափազանց ճնշման կիրառման։ Թեպետ նախկին հետազոտությունները նկարագրում էին սնման խանգարումները առավելապես որպես հոգեբանական, շրջակա միջավայրի և հասարակական-մշակութային գործոնների հետ կապված խնդիրներ, հետագա ուսումնասիրությունները բացահայտեցին տվյալներ գենետիկ բաղադրիչի առկայության մասին[24]

Ժառանգականություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Բազմաթիվ հետազոտություններ ցույց են տալիս սնման խանգարումների նկատմամբ ժառանգական նախատրամադրվածության առկայությունը[25][25][26]։ Երկվորյակների ուսումնասիրությունները հայտնաբերել են ժառանգական փոփոխականության թեթև դեպքեր անորեքսիայի և բուլիմիայի տարբեր չափորոշիչները որպես ամբողջական խանգարման զարգացմանը նպաստող էնդոֆենոտիպեր դիտարկելիս[23]։ 1-ին քրոմոսոմի շրջանում հայտնաբերված է ժառանգական կապ անորեքսիա ունեցող անհատի ընտանիքի անդամների միջև[24]։ Անհատը, ով առաջին աստիճանի ազգակից է այնպիսի մարդու, որն ունեցել է կամ ունի սնման խանգարում, 7-12 անգամ ավելի մեծ հավանականությամբ կարող է ունենալ սնման խանգարում[27]։ Երկվորյակների հետազոտությունները ցույց են տալիս նաև, որ սնման խանգարումների զարգացման նկատմամբ ընկալունակությունը առնվազն որոշակիորեն կարող է ժառանգված լինել, և կան տվյալներ, որոնք ցույց են տալիս անորեքսիայի զարգացմանը հակված լինելու գենետիկ լոկուսի առկայությունը[27]։ Սնման խանգարումների դեպքերի 50% վերագրվում է ժառանգականությանը[28]։ Մյուս դեպքերը արտաքին պատճառների կամ զարգացման խնդիրների արդյունքներ են[29]։ Կան նաև այլ նյարդակենսաբանական գործոններ` կապված զգայական ռեակտիվության և իմպուլսիվության հետ, որոնք կարող են հանգեցնել գերսնման և դուրսբերման (սննդից ազատման) վարքագծի[30]։

Էպիգենետիկական մեխանիզմները միջոցներ են, որոնցով շրջակա միջավայրի ազդեցությունները փոփոխում են գենի արտահայտումն (էքսպրեսիան) այնպիսի մեթոդներով, ինչպիսին օրինակ ԴՆԹ-մեթիլացումն է․ սրանք անկախ են և չեն ազդում ԴՆԹ հաջորդականության վրա։ Նրանք ժառանգական են, բայց կարող են ի հայտ գալ նաև կյանքի ընթացքում՝ լինելով դարձելի։ Դոպամինէրգիկ նյարդափոխանցման ապակարգավորումը էպիգենետիկական մեխանիզմների շնորհիվ ներգրավված է զանազան սնման խանգարումների մեջ[31]։ Սնման խանգարումներում էպիգենետիկական ուսումնասիրությունների համար հավակնող այլ գեները ներառում են լեպտինը, նախաօփիոմելանոկորտինը և ուղեղային ծագման նեյրոտրոֆիկ գործոնը[32]։

Հոգեբանական[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Սնման խանգարումները դասակարգված են որպես Առանցք I[33] խանգարումներ Հոգեկան առողջության խանգարումների ախտորոշիչ և վիճակագրական ձեռնարկում, որը հրատարակված է Ամերիկյան հոգեբուժական ասոցիացիայի կողմից։ Կան բազմազան այլ հոգեբանական խնդիրներ, որոնք կարող են ազդել սնման խանգարումների վրա․ որոշները համապատասխանում են Առանցք I ախտորոշման կամ անձնային խանգարման չափորոշիչներին, որոնք համակարգվում են որպես Առանցք II և հետևաբար դիտարկվում են որպես ախտորոշված սնման խանգարմանն ուղեկցող խնդիրներ։ Առանցք II խանգարումները ենթաբաժանվում են 3 խմբերի՝ A, B և C։ Պատճառահետևանքային կապը անձնային և սնման խանգարումների միջև դեռևս լիովին հաստատված չէ[34]։ Որոշ մարդիկ ունեն նախորդող խանգարում, որը կարող է բարձրացնել խոցելիությունը սնման խանգարման զարգացման նկատմամբ [35][36][37]։ Որոշ մարդկանց մոտ այն զարգանում է հետագայում[38]։ Սնման խանգարման ախտանիշների ծանրությունը և տեսակը ազդում են համակցման վրա[39]։ ԱՎՁ-IV չպետք է օգտագործվի ոչ մասնագետների կողմից ինքնախտորոշման համար, քանի որ անգամ մասնագետների կողմից կիրառվելիս առկա են լինում զգալի հակասություններ՝ կապված զանազան ախտորոշումներում (այդ թվում՝ սնման խանգարումներում) գործածվող ախտորոշիչ չափանիշների հետ։ Եղել են հակասություններ ԱՎՁ-ի տարբեր հրատարակությունների միջև՝ ներառյալ վերջին հրատարակությունը՝ ԱՎՁ-V, (2013 թվականի մայիս)[40][41][42][43][44]:

Ճանաչողական-ուշադրության շեղման խնդիրներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ուշադրության շեղումները կարող են ազդել սնման խանգարումների վրա։ Իրականացվել են բազմաթիվ ուսումնասիրություններ այս վարկածը ստուգելու համար։

Անհատականության հատկանիշներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Մանկական տարիքում դիտվող անհատականության զանազան հատկանիշներ կապված են սնման խանգարումների զարգացման հետ[59]։ Չափահասության տարիքում այս հատկանիշները կարող են ուժգնանալ՝ ի հաշիվ հոգեբանական և մշակութային ազդեցությունների, ինչպիսիք են դեռահասության հետ կապված հորմոնային փոփոխությունները, իրենցից ակնկալվող հասունության պահանջի հետ կապակցված սթրեսը և հասարակական-մշակութային ազդեցություններն ու ընկալվող սպասելիքները, հատկապես մարմնակազմվածքին առնչվող հարցերում։ Սնման խանգարումները փոխկապակցված են փխրուն և զգայուն ինքնաընկալման և մտածողության խանգարման հետ[60]։ Անհատականության շատ հատկանիշներ ունեն ժառանգական բաղադրիչ և բարձր ժառանգական փոխանցելիություն։ Որոշակի հատկանիշների քիչ հարմարողական մակարդակները կարող են ձեռք բերվել որպես արդյունք այնպիսի իրավիճակների, ինչպիսիք են գլխուղեղի անօքսիկ կամ տրավմատիկ վնասումը, նյարդադեգեներատիվ հիվանդությունները, ինչպիսին Պարկինսոնի հիվանդությունն է, նյարդաթունավորումը, օրինակ՝ կապարի ազդեցությունը, բակտերիալ վարակը, օրինակ՝ Լիմի հիվանդությունը կամ մակաբուծային վարակը, ինչպիսին է Toxoplasma gondii -ն, ինչպես նաև հորմոնային ազդեցությունները։ Հետազոտությունները շարունակվում են՝ կիրառելով արտապատկերման բազմազան եղանակներ, ինչպիսին է ֆունկցիոնալ մագնիսառեզոնանսային արտապատկերումը․ ցույց է տրվել, որ այս հատկանիշները սկիզբ են առնում գլխուղեղի տարբեր շրջաններում[61], օրինակ՝ ամիգդալա[62][63] և նախաճակատային կեղև[64]։ Նախաճակատային կեղևի և կատարողական ֆունկցիոնալ համակարգի խանգարումները ազդում են սնման վարքագծի վրա[65][66]։

Ցելիակիա[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Աղեստամոքսային խանգարումներ ունեցող մարդկանց մոտ խանգարված սնման սովորույթների զարգացման հավանականությունն ավելի մեծ է, քան ընդհանուր բնակչության շրջանում, ինչը վերաբերում է հատկապես սահմանափակող սնման խանգարումներին[67]։ Հայտնաբերված է որոշակի փոխկապակցվածություն անորեքսիայի և ցելիակիայի միջև։ Սնման խանգարումների զարգացման մեջ աղեստամոքսային ախտանիշները բավականին բարդ դեր են խաղում։ Որոշ հեղինակներ նշում են, որ աղեստամոքսային հիվանդություն ախտորոշմանը նախորդող չլուծված ախտանիշները կարող են այս մարդկանց մոտ սննդի նկատմամբ հակակրանք և զզվանք առաջացնել՝ վերափոխելով նրանց սննդային վարքագիծը։ Այլ հեղինակներ նշում են, որ ախտանիշների արտահայտմանը զուգընթաց մեծանում է նաև վտանգը։ Հաստատված է, որ ցելիակիա, գրգռված աղու համախտանիշ և բորբոքված աղու հիվանդություն ունեցող մարդիկ, ովքեր գիտակից չեն սննդակարգը խստորեն պահպանելու կարևորությանը, հաճախ նախընտրում են օգտագործել գրգռող սնունդ քաշի կորուստը խթանելու նպատակով։ Մյուս կողմից, ճիշտ սննդակարգին հետևող մարդկանց մոտ կարող է զարգանալ անհանգստություն, հակակրանք սննդի նկատմամբ և սնման խանգարումներ՝ պայմանավորված իրենց սննդի խաչաձև աղտոտման մտահոգությամբ։ Կան հեղինակներ, ովքեր առաջարկում են բժիշկներին գնահատել չբացահայտված ցելիակիայի առկայությունը սնման խանգարումներ ունեցող բոլոր մարդկանց մոտ, հատկապես, եթե նրանք ներկայացնում են որևէ աղեստամոքսային ախտանիշ (օրինակ՝ ախորժակի նվազում, որովայնային ցավ, վքնածություն, ձգվածություն, փսխում, փորլուծություն կամ փորկապություն), քաշի կորուստ, աճի խանգարում, ինչպես նաև հարցում կատարել ցելիակիա ունեցող հիվանդների մոտ մարմնի զանգվածի կամ ձևի հետ կապված մտահոգությունների, քաշի վերահսկման համար սննդակարգ պահելու կամ փսխմանը դիմելու մասին, գնահատել սնման խանգարումների հնարավոր առկայությունը[68], հատկապես կանանց մոտ[69]։

Շրջակա միջավայրի ազդեցություններ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Երեխայի նկատմամբ վատ վերաբերմունք[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Երեխայի նկատմամբ դաժան վերաբերմունքը, որը ներառում է ֆիզիկական, հոգեբանական և սեռական ոլորտները, ինչպես նաև անտեսումն ու արհամարհանքը մոտավորապես եռապատկում են սնման խանգարումների վտանգը[70]։ Սեռական բռնությունը գրեթե կրկնապատկում է բուլիմիայի ռիսկը, մինչդեռ անորեքսիայի հետ կապը պարզորոշ չէ[70]։

Հասարակական մեկուսացում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Հասարակական մեկուսացումը կորստաբեր ազդեցություն ունի անհատի ֆիզիկական և հուզական բարօրության վրա։ Նրանք, ովքեր մեկուսացած են հասարակությունից, ունեն մահացության ավելի բարձր ցուցանիշ՝ ի համեմատ հասարակական փոխհարաբերություններ հաստատած անձանց։ Ազդեցությունը մահացության վրա զգալիորեն ավելի բարձր է այն մարդկանց մոտ, ովքեր ունեն նախապես գոյություն ունեցող բժշկական կամ հոգեբուժական ախտաբանական վիճակներ․ այս դեպքում դիտվել են առավելապես սրտի պսակային (կորոնար) հիվանդության դեպքեր։ «Հասարակական մեկուսացման հետ կապված ռիսկն իր մեծությամբ համեմատելի է ծխելու և այլ կենսաբժշկական և հոգեհասարակական ռիսկի գործոնների հետ» (Բրումմետ և այլք)։

Հասարակական մեկուսացումը կարող է լինել սթրեսածին, ընկճող և տագնապահարույց։ Փորձելով բարելավել այս սթրեսային զգացողությունները՝ անձը կարող է տարվել հուզական (զգայական) շատակերությամբ, որի դեպքում սնունդը ծառայում է որպես հարմարավետության աղբյուր։ Հասարակական մեկուսացման միայնությունը և մշտական սթրեսային ազդակները դիտվում են նաև որպես գերսնման առաջացման գործոններ[71][72][73][74]։

Ուոլլերը, Կեններլին և Օհանյանը (2007 թվական) վիճաբանում են այն հարցի շուրջը, որ և գերսնման/փսխման, և սահմանափակման խանգարումները հույզերը ճնշելու մարտավարություններ են, պարզապես օգտագործվում են տարբեր ժամանակահատվածներում։ Օրինակ, սահմանափակումը կիրառվում է որևէ հուզական ակտիվություն կանխելու համար, մինչդեռ գերսնում/փսխում դիտվում է, երբ հույզերն արդեն իսկ ակտիվացված են[75]։

Ծնողական ազդեցություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Ծնողական ազդեցությունը երեխաների մոտ սնման խանգարումների զարգացման բնորոշ բաղադրիչ է։ Այս ազդեցությունը դրսևորվում և ձևավորվում է մի շարք գործոնների բազմազանությամբ, ինչպիսիք են ընտանեկան ժառանգական նախատրամադրվածությունը, սննդակարգի ընտրությունը՝ թելադրված մշակութային կամ ազգային նախապատվություններով, ծնողների մարմնակազմվածքը և սնման վարքագիծը, իրենց երեխաների սնման վարքագծում նրանց ներգրավվածության և ակնկալիքների աստիճանը, ինչպես նաև ծնող-երեխա միջանձնային հարաբերությունը։ Այս ամենը դեր է խաղում՝ ի լրումն ընդհանուր ընտանեկան հոգեհասարակական մթնոլորտին և կերակրման կայուն միջավայրի առկայությանը կամ բացակայությանը։ Հաստատված է, որ ոչ բարեխիղճ ծնողական վարքագիծը կարևոր դեր ունի սնման խանգարումների զարգացման հարցում։ Ինչ վերաբերում է ծնողական ազդեցության ավելի նուրբ կողմերին, ապա ցույց է տրված, որ սնման սովորույթները հաստատվում են վաղ մանկության շրջանում, և դեռևս երկու տարեկան հասակում երեխաներին պետք է թույլ տրվի ինքնուրույն որոշել, թե երբ են իրենք հագեցած։ Հայտնաբերված է հստակ կապ գիրության և ծնողական ճնշման միջև, որ երեխան ավելի շատ ուտի։

Ապացուցված է, որ սննդակարգին առնչվող հարկադրանքն անարդյունավետ է երեխայի սնման վարքագիծը վերահսկելու համար։ Հակառակը, հոգատարությունը, սերը և ուշադրությունը դրական են ազդում երեխայի քմահաճության վրա, և ավելի բազմազան սննդակարգն ընդունելի է դառնում նրանց համար[76][77][78][79][80][81]։

Ադամսը և Քրեյնը (1980 թվական) ցույց են տվել, որ ծնողների վրա ազդում են կարծրատիպերը, որոնք որոշում են նրանց կողմից իրենց երեխայի մարմնի ընկալումը։ Այս բացասական կարծրատիպերն ազդում են նաև երեխայի կողմից իր մարմնի ընկալման և ինքնաբավության վրա[82]։ Հիլդա Բրուքը, ով առաջամարտիկ է սնման խանգարումների ուսումնասիրության ոլորտում, պնդում է, որ նյարդային անորեքսիան հաճախ ի հայտ է գալիս այն աղջիկների մոտ, որ գերազանց են սովորում, հնազանդ են և մշտապես փորձում են գոհացնել իրենց ծնողներին։ Նրանց ծնողները գերվերահսկման հակում ունեն և թերանում են իրենց երեխաների հույզերի արտահայտումը քաջալերելու հարցում՝ խոչընդոտելով իրենց դուստրերի կողմից սեփական զգացմունքներն ու ցանկություններն ընդունելուն։ Այսպիսի իշխող ընտանիքներում անգամ չափահաս կանայք հնարավորություն չունեն անկախ լինել, թեպետ գիտակցում են դրա անհրաժեշտությունը, ինչը հաճախ հանգեցնում է ապստամբության և դիմադրության։ Սննդի ընդունման վերահսկումը կարող է օգնել նրանց՝ տալով կառավարելու և վերահսկելու զգացում[83]։

Հասակակիցների կողմից ճնշում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Բազմազան հետազոտություններում, ինչպիսին է ՄակՆայթի հետազոտողների կողմից իրականացված ուսումնասիրությունը, հասակակիցների ճնշումը հաստատված է որպես դեռահասության և վաղ երտասարդության տարիքում մարմնակազմվածքի մասին մտահոգությունների և սնման նկատմամբ վերաբերմունքի ձևավորմանը նշանակալիորեն նպաստող հանգամանք։

Էլեոնոր Մաքին և համահեղինակ Աննեթ լա Գրեկան (Մայամիի համալսարան) ուսումնասիրել են Ֆլորիդայի ավագ դպրոցի 236 դեռահաս աղջիկների։ «Դեռահաս աղջիկների մտահոգություններն իրենց քաշի, այլոց կողմից իրենց ընկալման և այն մասին, որ հասակակիցներն ակնկալում են իրենց նիհար տեսնել, նշանակալիորեն կապված են քաշը վերահսկող վարքագծի հետ», - ասում է Էլեոնար Մաքին (Երեխաների ազգային բժշկական կենտրոն Վաշինգտոնում), ով «Նրանք իրապես կարևոր են» հոդվածի հեղինակն է։

Հետազոտություններից մեկի համաձայն, 9 և 10 տարեկան աղջիկների 40% արդեն իսկ փորձում են քաշ կորցնել[84]։ Այսպիսի վարքագծի վրա իր ազդեցությունն է ունենում հասակակիցների պահվածքը․ հատուկ սննդակարգ պահպանող դեռահասների մեծամասնությունը նշում է, որ իրենց ընկերները ևս հետևում են հատուկ սննդակարգի։ Դեռահասների կողմից կատարվող ընտրությունները նշանակալիորեն կապված են այն ընկերների թվաքանակի հետ, ովքեր փորձում են նիհարել կամ իրենց են ստիպում հետևել սննդակարգի[85][86][87][88]։

Ընտրյալ մարզիկների մոտ դիտվում է սնման խանգարումների բարձր հաճախականություն։ Կին մարզիկները, ինչպիսիք են մարմնամարզիկները, բալետի պարուհիները, սուզորդները և այլք, գտնվում են առավելագույն ռիսկի գոտում։ 13-30 տարեկան տարիքային խմբում կանայք ավելի հակված են սնման խանգարումների զարգացմանը, քան տղամարդիկ։ Տղամարդիկ կազմում են նրանց 0-15%[89]:

Մշակութային ճնշում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

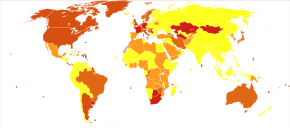

Հատկապես արևմտյան հասարակությունում առկա է նիհարությունը խրախուսող լայն տարածում գտած մշակութային շեշտադրում։ Երեխայի՝ ԶԼՄ-ների կողմից ներկայացվող կատարյալ մարմինն ունենալուն միտված արտաքին ճնշման ըմբռնումը կանխորոշում է երեխայի դժգոհությունն իր մարմնակազմվածքից, մարմնի ձևախեղման խանգարումը և սնման խանգարումը[90]։ «Մշակութային ճնշումը կանանց և տղամարդկանց վրա, որը դրդում է «կատարյալ» լինել, սնման խանգարումների զարգացման համար կարևոր նախատրամադրող գործոն է»[91][92]։ Ավելին, երբ տարբեր ռասաներին պատկանող կանայք կառուցում են իրենց ինքնագնահատականը մշակութայնորեն կատարյալ համարվող մարմնի հետ համեմատության հիման վրա, սնման խանգարումների հաճախականությունը բարձրանում է[93]։ Սնման խանգարումները ներկայումս լայն տարածում են գտնում նաև ոչ Արևմտյան երկրներում, որտեղ նիհար լինելը չի համարվում կատարելություն․ սա ցույց է տալիս, որ հասարակական և մշակութային ճնշումները սնման խանգարումների միակ պատճառը չեն[94]։ Ոչ Արևմտյան երկրներում կատարված դիտարկումներն անորեքսիայի վերաբերյալ մատնանշում են, որ խանգարումը «մշակութակապակցված» չէ, ինչպես նախկինում ընդունված էր մտածել[95]։ Այնուհանդերձ, բուլիմիայի հաճախականության ուսումնասիրությունները ենթադրում են, որ այն կարող է պայմանավորված լինել մշակութային ազդեցությամբ։ Ոչ Արևմտյան երկրներում բուլիմիան ավելի քիչ տարածում ունի, քան անորեքսիան, բայց երկրները, որտեղ այն դիտվում է, հավանաբար կամ անկասկած, ենթարկվել են Արևմտյան մշակույթի և գաղափարախոսության ազդեցությանը[96]։

Հասարակական-տնտեսական կարգավիճակը (ՀՏԿ) դիտվում է որպես ռիսկի գործոն սնման խանգարումների համար՝ ենթադրելով, որ լայն հնարավորությունների տիրապետելը թույլ է տալիս ընտրել համապատասխան սննդակարգ և նվազեցնել մարմնի զանգվածը[97]։ Որոշ հետազոտություններ ցույց են տվել փոխկապակցվածություն սեփական մարմնակազմվածքից ունեցած դժգոհության աճի և ՀՏԿ-ի աճի միջև[98]։ Այնուամենայնիվ, երբ անհատը հասնում է բարձր հասարակական-տնտեսական կարգավիճակի, այս փոխհարաբերությունը թուլանում է, իսկ որոշ դեպքերում՝ դադարում գոյություն ունենալ[95]։

Առավելապես ԶԼՄ-ներով է պայմանավորված մարդկանց կողմից սեփական անձի ընկալումը։ Անթիվ ամսագրեր և գովազդային վահանակներ պատկերում են նիհար հայտնի մարդկանց (Լինդսի Լոհան, Նիկոլ Ռիչի, Վիկտորյա Բեքհեմ, Մերի Քեյթ Օլսեն), ովքեր մեծ ուշադրության են արժանանում իրենց տեսքի շնորհիվ։ Հասարակությունը սովորեցրել է մարդկանց, որ անհրաժեշտ է ցանկացած գնով հասնել ընդունելության մյուսների կողմից[99]։ Դժբախտաբար, սա հանգեցրել է այն համոզմունքին, որ տվյալ շրջանակին համապատասխանելու համար պետք է խիստ որոշակի տեսք ունենալ։ Գեղեցկության մրցույթները, ինչպիսին Միսս Ամերիկա մրցույթն է, նպաստում են գեղեցիկ լինելու մասին պատկերացման ձևավորմանը, քանի որ մրցակիցները գնահատվում են որոշակի հատկանիշների հիման վրա[100]։

Ի լրումն հասարակական-տնտեսական կարգավիճակի, որը դիտարկվում է որպես մշակութային ռիսկի գործոն, պետք է նշել նաև սպորտային աշխարհը։ Մարզիկները և սնման խանգարումները հակված են քայլել ձեռք ձեռքի տված, հատկապես այն սպորտաձևերը, որոնցում քաշը մրցակցային գործոն է։ Մարմնամարզությունը, ձիավարությունը, ըմբշամարտը, բոդիբիլդինգը և պարն ընդամենը մի քանիսն են զանգված-կախյալ սպորտաձևերից։ Սնման խանգարումներն այն անհատների մոտ, ովքեր մասնակցում են մրցակցային ակտիվությունների (հատկապես կանայք), հաճախ հանգեցնում են մարմնի զանգվածի հետ կապված ֆիզիկական և կենսաբանական փոփոխությունների, որոնք հաճախ նմանվում են նախադեռահասային փուլերին։ Շատ հաճախ կանայք կորցնում են իրենց մրցակցային առավելությունը մարմնի փոփոխության հետևանքով, ինչը ստիպում է նրանց ծայրահեղ միջոցներ ձեռնարկել` պահպանելու համար իրենց ավելի երիտասարդ մարմնակազմվածքը։ Տղամարդկանց մոտ հաճախադեպ է գերսնումը, որին հաջորդում է չափից շատ մարզումը՝ կենտրոնանալով մկանային զանգվածի ավելացման, ոչ թե ճարպի կորստի վրա, սակայն նման տարվածությունը մկանային զանգվածի ավելացմամբ սնման խանգարում է ճիշտ նույնքան, որքան նիհար լինելու մոլուցքը։ Ներքոհիշյալ վիճակագրությունը, որը վերցված է Սյուզեն Նոլեն-Հոիկսեմայի գրքից (Ոչ նորմալ հոգեբանություն), ցույց է տալիս մարզիկների տոկոսը, ովքեր տառապում են սնման խանգարումներով՝ հիմնված սպորտային կատեգորիայի վրա։

- Էսթետիկ սպորտաձևեր (պար, գեղասահք, մարմնամարզություն) - 35%

- Զանգվածակախյալ սպորտաձևեր (ձյուդո, ըմբշամարտ) - 29%

- Դիմացկունության սպորտաձևեր (հեծանվավազք, լող, վազք) - 20%

- Տեխնիկական սպորտաձևեր (գոլֆ, բարձրացատկ) - 14%

- Գնդակով խաղեր (վոլեյբոլ, ֆուտբոլ) - 12%

Թեպետ այս մարզիկների մեծամասնության մոտ սնման խանգարումները զարգանում են իրենց մրցակցային առավելությունը պահելու համար, մյուսներն իրենց քաշը և կառուցվածքը պահպանում են մարզումների շնորհիվ: Սա նույնքան լուրջ է, որքան սննդի ընդունման սահմանափակումը հանուն մրցությունների: Թեպետև ապացույցները հստակ չեն, թե որ պահից սկսած են մարզիկները ձեռք բերում սնման խանգարումներ, հետազոտությունները ցույց են տալիս, որ անկախ մրցակցության մակարդակից` բոլոր մարզիկները ենթակա են սնման խանգարումների զարգացման ավելի բարձր ռիսկի, քան ոչ մարզիկները, հատկապես այնպիսի սպորտաձևերում, որտեղ նիհար լինելը մրցակցային գործոն է[101]:

Համասեռամոլների շրջանում ևս արհայտված է հասարակական ճնշման դերը: Համասեռամոլ տղամարդիկ ենթակա են սնման խանգարումների ախտանիշների զարգացման ավելի բարձր ռիսկի: Գեյ-մշակույթում զարգացած մկանունք ունենալը տալիս է ինչպես հասարակական, այնպես էլ սեռական գրավչության առավելություն, բացի այդ` ուժ և իշխանություն: Այն ճնշումներն ու գաղափարները, որ համասեռամոլ տղամարդը ցանկանում է ունենալ բարեկազմ կողակից, կարող են հանգեցնել սնման խանգարումների: Որքան բարձր է սնման խանգարումների ախտանիշների արտահայտումը, այնքան մեծ է մտահոգությունը, թե մյուսներն իրենց ինչպես են ընկալում, ինչպես նաև ավելի հաճախակի և ծանրաբեռնված են մարզումները[102]: Սեփական մարմնից ունեցած դժգոհությունը կապված է նաև արտաքին ճնշման հետ, որը դրդում է մարզվել, ինչպես նաև այն հանգամանքի, որ տարիքի հետ մարմնակազմվածքը կորցնում է նախկին գրավչությունը: Այնուամենայնիվ, բարեկազմ և զարգացած մկանային զանգվածով մարմինն ունենալն ավելի բնորոշ է երիտասարդ համասեռամոլ տղամարդկանց[103][102]:

Կարևոր է հասկանալ այն սահմանափակումներն ու խնդիրները, որոնք առկա են մշակույթի, ազգային պատկանելության և ՀՏԿ-ի դերն ուսումնասիրող տարբեր հետազոտությունների ժամանակ: Միջմշակութային ուսումնասիրություններից շատերը կիրառում են ԱՎՁ-IV-ի սահմանումները, որոնք քննադատվում են Արևմտյան մշակույթի առանձնահատկություններն արտացոլելու համար:

Հետևաբար, հարցադրումներն ու գնահատականները կարող են չհայտնաբերել սնման խանգարումների հետ կապված մշակութային տարբերությունները: Սակավաթիվ հետազոտություներ փորձել են պարզել Արևմտյան մշակույթի անմիջական ազդեցությանը ենթարկված շրջաններում մարդկանց կողմից այդ մշակույթի ընդունման կամ ավանդական արժեքների պահպանման հակվածությունն ու ցուցանիշները: Եվ վերջապես, սնման խանգարումների և մարմնակազմվածքի ընկալման խախտումների միջմշակութային հետազոտությունների մեծամասնությունն իրականացվել է Արևմտյան ազգերի շրջանում, ոչ թե հետազոտվող երկրներում կամ շրջաներում[104]:

Թեպետ շատ ազդեցություններ են որոշում, թե անհատն իր մարմնակազվածքն ինչպես է ընկալում և փոխակերպում, ԶԼՄ-ները հիմնական դեր են խաղում այս հարցում: Ծնողների ազդեցությունը, հասակակիցների կարծիքը և սեփական արդյունավետության ու կարողությունների մասին ունեցած գաղափարները ևս ազդում են անհատի ինքնաընկալման վրա: Սնման խանգարումների խնդիրն աշխարհասփյուռ է, և չնայած նրան, որ կանայք ավելի հակված են նման խանգարումների զարգացմանը, այն ախտահարում է երկու սեռերին էլ (Շվիցեր 2012 թվական):

ԶԼՄ-ներն ազդում են սնման խանգարումների վրա թե՛ դրական, թե՛ բացասական լույսի ներքո դրանք ներկայացնելիս: Հետևապես, նրանք ունեն զգուշություն դրսևորելու պատասխանատվություն, երբ խթանում են կատարելությունն արտացոլող պատկերների առաջխաղացումը, որոնց հասնելու ձգտման արդյունքում շատ մարդկանց մոտ զարգանում են սնման խանգարումներ[105]:

Փորձելով որոշակիորեն ազդել նորաձևության աշխարհում առկա անառողջ իրավիճակի վրա, Ֆրանսիայում 2015 թվականին ընդունվեց օրենք, ըստ որի` մոդելները պետք է բժշկի կողմից առողջ համարվեն, որպեսզի կարողանան մասնակցել նորաձևության ցուցադրությունների: Օրենքը պահանջում է նաև, որ ամսագրերի նկարները համապատասխանեն իրականությանը[106]:

Հատկապես Արևմտյան կիսագնդում առկա է հստակ կապ սոցիալական ցանցերում «բարեկազմ իդեալի» տարածվածության, սեփական մարմնից ունեցած դժգոհության և սնման խանգարումների միջև[107]: Նոր հետազոտությունը հաստատում է սոցիալական ցանցերում աղավաղված պատկերների տարածման «միջազգայնացումը», ինչպես նաև բացասական համեմատությունների առկայությունը չափահաս երիտասարդ կանանց շրջանում[108]: Հետազոտությունների մեծամասնությունն անցկացվել է ԱՄՆ-ում, Մեծ Բրիտանիայում, Ավստրալիայում, որտեղ բարեկազմ իդեալը և կատարյալ մարմին ունենալու ձգտումը լայն տարածում ունեն կանանց շրջանում[108]:

Ի լրումն լրատվամիջոցների ազդեցությանը, կան նաև սնման խանգարումների տարածմանը նպաստող տարբեր հարթակներ (անձնական բլոգ, Թվիթեր և այլն), որտեղ անորեքսիան խրախուսող համայնքը դիտարկում է սնման խանգարումը որպես ապրելակերպ` շարունակաբար տեղադրելով հյուծված մարմինների նկարներ և նիհար մնալու գաղտնիքներ: #proana հեշտեգը այս համայնքի արտադրանքն է[109], ինչպես նաև մարմնի զանգվածի նվազումը խրախուսող նկարները` նշելով «նիհարաշնչանք» (“thinspiration”): Հասարակական համեմատության տեսության համաձայն` երիտասարդ կանայք հակում ունեն համեմատել իրենց արտաքին տեսքը այլոց հետ, ինչը կարող է հանգեցնել սեփական մարմնի բացասական ընկալման և սնման վարքագծի փոփոխության, որը կարող է զարգանալ` դառնալով խանգարված սնման վարքագիծ[110]:

Երբ առանձին մարմնամասեր մեկուսացվում են և ցուցադրվում լրատվամիջոցներում որպես դիտարկման առարկաներ, սա կոչվում է առարկայականացում. կանանց վրա ազդում է առավելապես հենց այս երևույթը: Այս դեպքում կանայք գնահատում են իրենց մարմնի մասերը որպես գովասանքի և այլոց հաճույք պատճառելու միջոց: Առկա է նշանակալի կապ ինքնառարկայականացման, սեփական մարմնից դժգոհության և խանգարված սնման միջև, քանի որ գեղեցկության մասին պատկերացումը վերափոխվում է ԶԼՄ-ների միջոցով[107]:

Մեխանիզմներ[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- Կենսաքիմիական. սնման վարքագիծը համակարգային գործընթաց է, որը վերահսկվում է նյարդաներզատական (նեյրոէնդոկրրին) համակարգի կողմից: Վերջինիս գլխավոր բաղադրիչը Ենթատեսաթումբ-մակուղեղ-մակերիկամային (հիպոթալամուս-հիպոֆիզ-ադրենալային) առանցքն է (ԵՄՄ առանցք): Այս առանցքում առկա կարգավորման խանգարումները կապակցված են սնման խանգարումների հետ[111][112]: Այդպիսի խանգարումներին են պատկանում որոշակի նեյրոտրանսմիտորների, հորմոնների[113] կամ նեյրոպեպտիդների[114] և ամինոացիդների (օրինակ` հոմոցիստեինի, որի մակարդակի բարձրացումը բնորոշ է անորեքսիային և բուլիմիային ճիշտ այնպես, ինչպես ընկճախտին) արտադրության, քանակի և փոխանցման ապակարգավորումները[115]:

- Սերոտոնին. ընկճախտում ներգրավված նեյրոտրանսմիտոր, որն ունի արգելակող ազդեցություն սնման վարքագծի վրա[116][117][118][119][120]:

- Նորէպինեֆրինը և՛ նեյրոտրանսմիտոր է, և՛ հորմոն. երկու ազդեցություններում դիտվող անկանոնություններն էլ կարող են բացասաբար ազդել սնման վարքագծի վրա[121][122]:

- Դոպամին. ի հավելումն նորէպինեֆրինի և էպինեֆրինի նախորդը լինելուն` այն նաև նեյրոտրանսմիտոր է, որը կարգավորում է սննդի օգտավետությունը[123][124]:

- Նեյրոպեպտիդ Y. հորմոն, որը խթանում է սնման գործընթացը և նվազեցնում նյութափոխանակության արագությունը[125]: Նեյրոպեպտիդ Y-ի մակարդակն արյան մեջ բարձրացած է նյարդային անորեքսիա ունեցող հիվանդների մոտ, և հետազոտությունները ցույց են տվել, որ այս հորմոնի ներարկումը սննդի ընդունման սահմանափակմամբ առնետների ուղեղի մեջ ավելացնում է ժամանակը, որը նրանք անցկացնում են անիվի վրա վազելիս: Հորմոնը խթանում է սննդի ընդունումն առողջ մարդկանց մոտ, սակայն սովահարության պայմաններում այն բարձրացնում է ակտիվության մակարդակը` միգուցե սնունդ հայթայթելու հնարավորությունը մեծացնելու համար[125]: Նեյրոպեպտիդ Y-ի բարձր մակարդակը սնման խանգարումներ ունեցող հիվանդների արյան մեջ կարող է որոշակիորեն բացատրել ծայրահեղ գերծանրաբեռնման դեպքերը նյարդային անորեքսիա ունեցող հիվանդների մեծամասնության մոտ:

- Լեպտին և գրելին. լեպտինը հիմնականում օրգանիզմի ճարպային բջիջների կողմից արտադրվող հորմոն է, որն արգելակող ազդեցություն ունի ախորժակի վրա` առաջացնելով հագեցման զգացողություն: Գրելինն ախորժակը խթանող հորմոն է, որն արտադրվում է ստամոքսում և բարակ աղիքի վերին հատվածում: Այս երկու հորմոնների շրջանառող և պարբերաբար փոփոխվող մակարդակները մարմնի զանգվածի վերահսկման կարևոր գործոններն են: Թեպետ հաճախ այս հորմոնները կապակցվում են գիրության հետ, այնուհանդերձ երկուսն էլ իրենց համապատասխան հետևանքներով ներգրավված են նյարդային անորեքսիայի և բուլիմիայի ախտաֆիզիոլոգիայում[126]: Լեպտինը կարող է օգտագործվել նաև տարբերակելու համար կառուցվածքային նիհարությամբ առողջ մարդուն նյարդային անորեքսիա ունեցող անհատից[127][128]:

- Աղիքային բակտերիաներ և իմունային համակարգ. ուսումնասիրությունները ցույց են տվել, որ նյարդային անորեքսիա և բուլիմիա ունեցող հիվանդների մեծամասնության մոտ դիտվում է աուտոհակամարմինների մակարդակի բարձրացում, որոնք ազդում են ախորժակի վերահսկումը և սթրեսային պատասխանը կարգավորող հորմոնների և նեյրոպեպտիդների վրա: Կարող է լինել ուղիղ համեմատական կապ աուտոհակամարմինների մակարդակի և հոգեբանական առանձնահատկությունների միջև[129][130]:

- Վարակ (ինֆեկցիա). ՄԱՆԽԿՍ (PANDAS), որը հապավումն է հետևյալի. Մանկական աուտոիմուն նյարդահոգեկան խանգարումներ` կապված ստրեպտոկոկային ինֆեկցիաների հետ: ՄԱՆԽԿՍ ունեցող երեխաներն ունենում են օբսեսիվ-կոմպուլսիվ խանգարում (կպչուն-սևեռուն խանգարում) և/կամ տիկ խանգարումներ, ինչպիսին է Տուրետի համախտանիշը: Կա հավանականություն, որ ՄԱՆԽԿՍ որոշ դեպքերում կարող է խթանիչ գործոն լինել նյարդային անորեքսիայի զարգացման համար[131]:

- Ախտահարումներ. ուսումնասիրությունները ցույց են տվել, որ աջ ճակատային բլթի կամ քունքային բլթի ախտահարումները կարող են առաջացնել սնման խանգարումների ախտաբանական ախտանիշներ[132][133][134]:

- Ուռուցքներ. ուղեղի տարբեր շրջաններում առկա ուռուցքները ներգրավված են եղել ոչ նորմալ սնման սովորույթների զարգացման գործընթացում[135][136][137][138][139]:

- Ուղեղի կրակալում. ուսումնասիրություններից մեկը լուսաբանում է դեպք, որում աջ տեսաթմբի նախորդող կրակալումը կարող է նպաստած լինել նյարդային անորեքսիայի զարգացմանը[140]:

- Gut bacteria and immune system: studies have shown that a majority of patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa have elevated levels of autoantibodies that affect hormones and neuropeptides that regulate appetite control and the stress response. There may be a direct correlation between autoantibody levels and associated psychological traits.[129][130] Later study revealed that autoantibodies reactive with alpha-MSH are, in fact, generated against ClpB, a protein produced by certain gut bacteria e.g. Escherichia coli. ClpB protein was identified as a conformational antigen-mimetic of alpha-MSH. In patients with eating disorders plasma levels of anti-ClpB IgG and IgM correalated with patients' psychological traits[141]

- Infection: PANDAS, is an abbreviation for Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections. Children with PANDAS "have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and/or tic disorders such as Tourette syndrome, and in whom symptoms worsen following infections such as "sterp throat" and scarlet fever". (NIMH) There is a possibility that PANDAS may be a precipitating factor in the development of anorexia nervosa in some cases, (PANDAS AN).[131]

- Lesions: studies have shown that lesions to the right frontal lobe or temporal lobe can cause the pathological symptoms of an eating disorder.[132][133][134]

- Tumors: tumors in various regions of the brain have been implicated in the development of abnormal eating patterns.[135][136][137][138][139]

- Brain calcification: a study highlights a case in which prior calcification of the right thalumus may have contributed to development of anorexia nervosa.[140]

- somatosensory homunculus: is the representation of the body located in the somatosensory cortex, first described by renowned neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield. The illustration was originally termed "Penfield's Homunculus", homunculus meaning little man. "In normal development this representation should adapt as the body goes through its pubertal growth spurt. However, in AN it is hypothesized that there is a lack of plasticity in this area, which may result in impairments of sensory processing and distortion of body image". (Bryan Lask, also proposed by VS Ramachandran)

- Obstetric complications: There have been studies done which show maternal smoking, obstetric and perinatal complications such as maternal anemia, very pre-term birth (less than 32 weeks), being born small for gestational age, neonatal cardiac problems, preeclampsia, placental infarction and sustaining a cephalhematoma at birth increase the risk factor for developing either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Some of this developmental risk as in the case of placental infarction, maternal anemia and cardiac problems may cause intrauterine hypoxia, umbilical cord occlusion or cord prolapse may cause ischemia, resulting in cerebral injury, the prefrontal cortex in the fetus and neonate is highly susceptible to damage as a result of oxygen deprivation which has been shown to contribute to executive dysfunction, ADHD, and may affect personality traits associated with both eating disorders and comorbid disorders such as impulsivity, mental rigidity and obsessionality. The problem of perinatal brain injury, in terms of the costs to society and to the affected individuals and their families, is extraordinary. (Yafeng Dong, PhD)[142][143][144][145][146][147][148][149][150][151][152]

- Symptom of starvation: Evidence suggests that the symptoms of eating disorders are actually symptoms of the starvation itself, not of a mental disorder. In a study involving thirty-six healthy young men that were subjected to semi-starvation, the men soon began displaying symptoms commonly found in patients with eating disorders.[125][153] In this study, the healthy men ate approximately half of what they had become accustomed to eating and soon began developing symptoms and thought patterns (preoccupation with food and eating, ritualistic eating, impaired cognitive ability, other physiological changes such as decreased body temperature) that are characteristic symptoms of anorexia nervosa.[125] The men used in the study also developed hoarding and obsessive collecting behaviors, even though they had no use for the items, which revealed a possible connection between eating disorders and obsessive compulsive disorder.[125]

Ախտորոշում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Նախնական ախտորոշումը պետք է կատարվի համապատասխան և իրավասու բժշկական մասնագետի կողմից: «Բժշկական պատմությունն ամենազորեղ գործիքն է սնման խանգարումների ախտորոշման համար» (ամերիկացի ընտանեկան բժիշկ)[154]: Կան շատ բժշկական խանգարումներ, որոնք նմանվում են սնման խանգարումներին և համակցվում են հոգեբուժական խանգարումների հետ: Նախքան սնման խանգարում ախտորոշելը պետք է բացառել բոլոր օրգանական պատճառները կամ որևէ այլ հոգեբուժական խանգարման առկայությունը: Վերջին 30 տարիներին սնման խանգարումները դարձել են ավելի ու ավելի ակնբախ, և դեռևս հստակ չէ` արդյոք ներկայացված փոփոխություններն արտացոլում են իրական աճի պատկերը: Նյարդային անորեքսիան և բուլիմիան ամենահստակ սահմանված ենթախմբերն են սնման խանգարումների լայն շրջանակում: Շատ հիվանդներ ունեն այս երկու հիմնական ախտորոշումների ենթաշեմային դրսևորումներ, մյուսները` տարբեր ախտանիշներով և բնույթով[155]:

Medical[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

The diagnostic workup typically includes complete medical and psychosocial history and follows a rational and formulaic approach to the diagnosis. Neuroimaging using fMRI, MRI, PET and SPECT scans have been used to detect cases in which a lesion, tumor or other organic condition has been either the sole causative or contributory factor in an eating disorder. "Right frontal intracerebral lesions with their close relationship to the limbic system could be causative for eating disorders, we therefore recommend performing a cranial MRI in all patients with suspected eating disorders" (Trummer M et al. 2002), "intracranial pathology should also be considered however certain is the diagnosis of early-onset anorexia nervosa. Second, neuroimaging plays an important part in diagnosing early-onset anorexia nervosa, both from a clinical and a research prospective".(O'Brien et al. 2001).[134][156]

Psychological[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

| Eating Attitudes Test[157] | SCOFF questionnaire[158] |

| Body Attitudes Test[159] | Body Attitudes Questionnaire[160] |

| Eating Disorder Inventory[161] | Eating Disorder Examination Interview[162] |

After ruling out organic causes and the initial diagnosis of an eating disorder being made by a medical professional, a trained mental health professional aids in the assessment and treatment of the underlying psychological components of the eating disorder and any comorbid psychological conditions. The clinician conducts a clinical interview and may employ various psychometric tests. Some are general in nature while others were devised specifically for use in the assessment of eating disorders. Some of the general tests that may be used are the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale[163] and the Beck Depression Inventory.[164][165] longitudinal research showed that there is an increase in chance that a young adult female would develop bulimia due to their current psychological pressure and as the person ages and matures, their emotional problems change or are resolved and then the symptoms decline.[166]

Differential diagnoses[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

There are multiple medical conditions which may be misdiagnosed as a primary psychiatric disorder, complicating or delaying treatment. These may have a synergistic effect on conditions which mimic an eating disorder or on a properly diagnosed eating disorder.

- Lyme disease which is known as the "great imitator", as it may present as a variety of psychiatric or neurological disorders including anorexia nervosa.[167][168]

- Gastrointestinal diseases,[67] such as celiac disease, Crohn's disease, peptic ulcer, eosinophilic esophagitis[68] or non-celiac gluten sensitivity,[169] among others. Celiac disease is also known as the "great imitator", because it may involve several organs and cause an extensive variety of non-gastrointestinal symptoms, such as psychiatric and neurological disorders,[170][171][172] including anorexia nervosa.[68]

- Addison's Disease is a disorder of the adrenal cortex which results in decreased hormonal production. Addison's disease, even in subclinical form may mimic many of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa.[173]

- Gastric adenocarcinoma is one of the most common forms of cancer in the world. Complications due to this condition have been misdiagnosed as an eating disorder.[174]

- Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypoparathyroidism and hyperparathyroidism may mimic some of the symptoms of, can occur concurrently with, be masked by or exacerbate an eating disorder.[175][176][177][178][179][180][181][182]

- Toxoplasma seropositivity: even in the absence of symptomatic toxoplasmosis, toxoplasma gondii exposure has been linked to changes in human behavior and psychiatric disorders including those comorbid with eating disorders such as depression. In reported case studies the response to antidepressant treatment improved only after adequate treatment for toxoplasma.[183]

- Neurosyphilis: It is estimated that there may be up to one million cases of untreated syphilis in the US alone. "The disease can present with psychiatric symptoms alone, psychiatric symptoms that can mimic any other psychiatric illness". Many of the manifestations may appear atypical. Up to 1.3% of short term psychiatric admissions may be attributable to neurosyphilis, with a much higher rate in the general psychiatric population. (Ritchie, M Perdigao J,)[184]

- Dysautonomia: a wide variety of autonomic nervous system (ANS) disorders may cause a wide variety of psychiatric symptoms including anxiety, panic attacks and depression. Dysautonomia usually involves failure of sympathetic or parasympathetic components of the ANS system but may also include excessive ANS activity. Dysautonomia can occur in conditions such as diabetes and alcoholism.

Psychological disorders which may be confused with an eating disorder, or be co-morbid with one:

- Emetophobia is an anxiety disorder characterized by an intense fear of vomiting. A person so afflicted may develop rigorous standards of food hygiene, such as not touching food with their hands. They may become socially withdrawn to avoid situations which in their perception may make them vomit. Many who suffer from emetophobia are diagnosed with anorexia or self-starvation. In severe cases of emetophobia they may drastically reduce their food intake.[185][186]

- Phagophobia is an anxiety disorder characterized by a fear of eating, it is usually initiated by an adverse experience while eating such as choking or vomiting. Persons with this disorder may present with complaints of pain while swallowing.[187]

- Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is listed as a somatoform disorder that affects up to 2% of the population. BDD is characterized by excessive rumination over an actual or perceived physical flaw. BDD has been diagnosed equally among men and women. While BDD has been misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa, it also occurs comorbidly in 39% of eating disorder cases. BDD is a chronic and debilitating condition which may lead to social isolation, major depression and suicidal ideation and attempts. Neuroimaging studies to measure response to facial recognition have shown activity predominately in the left hemisphere in the left lateral prefrontal cortex, lateral temporal lobe and left parietal lobe showing hemispheric imbalance in information processing. There is a reported case of the development of BDD in a 21-year-old male following an inflammatory brain process. Neuroimaging showed the presence of a new atrophy in the frontotemporal region.[188][189][190][191]

Կանխարգելում[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Կանխարգելման նպատակն է խթանել առողջ զարգացումը նախքան սնման խանգարումների ի հայտ գալը: Այն ներառում է նաև սնման խանգարումների վաղ ախտորոշումը, քանի դեռ հնարավոր է բուժել դրանք: Արդեն 5-7 տարեկանում երեխաները գիտակցում են մարմնի տեսքին և սննդակարգին վերաբերող մշակութային ուղերձները: Կանխարգելումը գալիս է այս խնդիրները լուսաբանելու համար: Երեխաների հետ կարող են քննարկվել հետևյալ թեմաները (դեռահասների և երիտասարդ չափահասների հետ ևս):

- Զգացմունքային և հուզական խնդիրներ. հուզական լարմամբ պայմանավորված շատակերությունը քննարկելու լավագույն տարբերակը երեխային հարցնելն է, թե քաղցած լինելուց զատ ինչը կարող է ուտելու ցանկություն առաջացնել: Պետք է նրանց հետ խոսել հույզերը կառավարելու ավելի արդյունավետ եղանակների մասին` շեշտելով վստահելի մարդու հետ սեփական զգացմունքների մասին խոսելու կարևորությունն ու արժեքը:

- Ոչ ասել գրգռող կատակներին. կարևոր է բացատրել, որ սխալ է վիրավորական արտահայտություններ անել մյուս մարդկանց մարմնի չափերի մասին:

- Մարմնի լեզու. սեփական մարմնին լսելու կարևորությունը, այն է` ուտել, երբ քաղցած ես և դադարել ուտել, երբ բավարարված ես: Երեխաներն ինտուիտիվ կերպով հասկանում և ընկալում են այս գաղափարները:

- Առողջ ապրելակերպն ու մարզումներն օգտակար են բոլորի համար. պետք է տեղեկացնել երեխաներին մարմնի չափերի գենետիկայի և այն մասին, թե ինչ բնականոն փոփոխություններ են տեղի ունենում աճի ընթացքում: Պետք է քննարկել նրանց վախերն ու հույսերը մեծանալու մասին` կենտրոնանալով առողջ ապրելակերպի և հավասարկշռված սննդակարգի վրա:

Համացանցը և նորագույն տեխնոլոգիական միջոցները նոր հնարավորություններ են ընձեռում կանխարգելման համար: Կանխարգելման ծրագրերի զարգացումն ու տարածումն օնլայն հարթակների միջոցով հնարավորություն են տալիս հասնել մարդկանց լայն շրջանակի` ունենալով նվազագույն ծախսեր[192]: Այսպիսի մոտեցումը կարող է ապահովել նաև կանխարգելման ծրագրերի կայունությունը:

Treatment[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Treatment varies according to type and severity of eating disorder, and usually more than one treatment option is utilized.[193] Family doctors play an important role in early treatment of people with eating disorders by encouraging those who are also reluctant to see a psychiatrist.[194] Treatment can take place in a variety of different settings such as community programs, hospitals, day programs, and groups.[195] The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends a team approach to treatment of eating disorders. The members of the team are usually a psychiatrist, therapist, and registered dietitian, but other clinicians may be included.[196]

That said, some treatment methods are:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),[197][198][199] which postulates that an individual's feelings and behaviors are caused by their own thoughts instead of external stimuli such as other people, situations or events; the idea is to change how a person thinks and reacts to a situation even if the situation itself does not change. See Cognitive behavioral treatment of eating disorders.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy: a type of CBT[200]

- Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT), a set of cognitive drills or compensatory interventions designed to enhance cognitive functioning.[201][202][203][204]

- Dialectical behavior therapy[205]

- Family therapy[206] including "conjoint family therapy" (CFT), "separated family therapy" (SFT) and Maudsley Family Therapy.[207][208]

- Behavioral therapy: focuses on gaining control and changing unwanted behaviors.[209]

- Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)[210]

- Cognitive Emotional Behaviour Therapy (CEBT)[211]

- Music Therapy

- Recreation Therapy

- Art therapy[212]

- Nutrition counseling[213] and Medical nutrition therapy[214][215][216]

- Medication: Orlistat is used in obesity treatment. Olanzapine seems to promote weight gain as well as the ability to ameliorate obsessional behaviors concerning weight gain. zinc supplements have been shown to be helpful, and cortisol is also being investigated.[217][218][219][220][221][222]

- Self-help and guided self-help have been shown to be helpful in AN, BN and BED;[199][223][224][225] this includes support groups and self-help groups such as Eating Disorders Anonymous and Overeaters Anonymous.[226][227]

- Psychoanalysis

- Inpatient care

There are few studies on the cost-effectiveness of the various treatments.[228] Treatment can be expensive;[229][230] due to limitations in health care coverage, people hospitalized with anorexia nervosa may be discharged while still underweight, resulting in relapse and rehospitalization.[231]

For children with anorexia, the only well-established treatment is the family treatment-behavior.[232] For other eating disorders in children, however, there is no well-established treatments, though family treatment-behavior has been used in treating bulimia.[232]

Outcomes[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

Outcome estimates are complicated by non-uniform criteria used by various studies, but for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder, there seems to be general agreement that full recovery rates are in the 50% to 85% range, with larger proportions of people experiencing at least partial remission.[226][233][234][235] The outcomes of eating disorders (ED) vary among the cases. For many, it can be a lifelong struggle or it can be overcome within months. In the United States, twenty million women and ten million men have an eating disorder at least once in their lifetime.[236] The mortality rate for those with anorexia nervosa is 5.4 per 1000 individuals per year. Roughly 1.3 deaths were due to suicide. A person who is or had been in an inpatient setting had a rate of 4.6 deaths per 1000. Of individuals with bulimia nervosa about 2 persons per 1000 persons die per year and among those with EDNOS about 3.3 per 1000 people die per year.[237]

- Miscarriages: Pregnant women with a Binge Eating Disorder have shown to have a greater chance of having a miscarriage compared to pregnant women with any other eating disorders. According to a study done, out of a group of pregnant women being evaluated, 46.7% of the pregnancies ended with a miscarriage in women that were diagnosed with BED, with 23.0% in the control. In the same study, 21.4% of women diagnosed with Bulimia Nervosa had their pregnancies end with miscarriages and only 17.7% of the controls.[238]

- Relapse: An individual who is in remission from BN and EDNOS (Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified) is at a high risk of falling back into the habit of self-harm. Factors such as high stress regarding their job, pressures from society, as well as other occurrences that inflict stress on a person, can push a person back to what they feel will ease the pain. A study tracked a group of selected people that were either diagnosed with BN or EDNOS for 60 months. After the 60 months were complete, the researchers recorded whether or not the patients were suffering from a relapse. The results found that the probability of a person previously diagnosed with EDNOS had a 41% chance of relapsing; a person with BN had a 47% chance.[239]

- Attachment insecurity: People who are showing signs of attachment anxiety will most likely have trouble communicating their emotional status as well as having trouble seeking effective social support. Signs that a person has adopted this symptom include not showing recognition to their caregiver or when he/she is feeling pain. In a clinical sample, it is clear that at the pretreatment step of a patient's recovery, more severe eating disorder symptoms directly corresponds to higher attachment anxiety. The more this symptom increases, the more difficult it is to achieve eating disorder reduction prior to treatment.[240]

Anorexia Nervosa symptoms include the increasing chance of getting osteoporosis. This disease causes the bones of an individual to become brittle, weak, and low in density. Thinning of the hair as well as dry hair and skin are also very common. The muscles of the heart will also start to change if no treatment is inflicted on the patient. This causes the heart to have an abnormally slow heart rate along with low blood pressure. Heart failure becomes a major consideration when this begins to occur. Muscles throughout the body begin to lose their strength. This will cause the individual to begin feeling faint, drowsy, and weak. Along with these symptoms, the body will begin to grow a layer of hair called lanugo. The human body does this in response to the lack of heat and insulation due to the low percentage of body fat.[236]

Bulimia nervosa symptoms include heart problems like an irregular heartbeat that can lead to heart failure and death may occur. This occurs because of the electrolyte imbalance that is a result of the constant binge and purge process. The probability of a gastric rupture increases. A gastric rupture is when there is a sudden rupture of the stomach lining that can be fatal.The acids that are contained in the vomit can cause a rupture in the esophagus as well as tooth decay. As a result, to laxative abuse, irregular bowel movements may occur along with constipation. Sores along the lining of the stomach called peptic ulcers begin to appear and the chance of developing pancreatitis increases.[236]

Binge eating symptoms include high blood pressure, which can cause heart disease if it is not treated. Many patients recognize an increase in the levels of cholesterol. The chance of being diagnosed with gallbladder disease increases, which affects an individual's digestive tract.[236]

Համաճարակաբանություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

2010 թվականի տվյալներով սնման խանգարումները 7,000 մարդկանց մահվան պատճառ են հանդիսացել՝ դառնալով ամենաբարձր մահացություն ունեցող հոգեկան հիվանդությունները[241]։ Միացյալ նահանգներում կատարված հետազոտություններից մեկը հայտնաբերել է ավելի բարձր հաճախականություն քոլեջի այն ուսանողների շրջանում, ովքեր տրանսգենդեր են[242]։

Տնտեսական ազդեցություն[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- Սնման խանգարումների հիվանդանոցային բուժման ընդհանուր արժեքը 165 միլիոն դոլարից (2008-2009 թվականներին) բարձրացել է մինչև 277 միլիոն դոլար (2008-2009 թվականներին), որը կազմում է 68% աճ։ Սնման խանգարում ունեցող մեկ մարդու բուժման միջին արժեքը մեկ տասնամյակի ընթացքում աճել է 29%-ով՝ 7,300 դոլարից հասնելով 9,400 դոլարի։

- Մեկ տասնամյակի ընթացքում սնման խանգարումները ներառող հոսպիտալացումներն ավելի մեծաթիվ են դարձել բոլոր տարիքային խմբերում։ Առավելագույն աճը դիտվել է 45-65 տարեկան մարդկանց շրջանում՝ կազմելով 88%, որին հետևում է 12 տարեկանից ցածր տարիքային խմբում գտնվողների հոսպիտալացման ցուցանիշը (72%):

- Սնման խանգարումներ ունեցող և հիվանդանոցային բուժման ենթակա հիվանդների մեծամասնությունը կազմում են կանայք։ 2008-2009 թվականների ընթացքում դեպքերի 88% գրանցվել են կանանց և 12%` տղամարդկանց շրջանում։ Զեկույցը նաև ցույց է տվել սնման խանգարումներ ունեցող տղամարդկանց մոտ հոսպիտալացման աճ 53%-ով։

Տես նաև[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

References[խմբագրել | խմբագրել կոդը]

- ↑ Garner, DM; Garfinkel, PE (2009). «Socio-cultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa». Psychological Medicine. 10 (4): 647–56. doi:10.1017/S0033291700054945. PMID 7208724.

- ↑ Regard, M; Landis, T (1997). «"Gourmand syndrome": Eating passion associated with right anterior lesions». Neurology. 48 (5): 1185–90. doi:10.1212/wnl.48.5.1185. PMID 9153440.

- ↑ Jung, J; Lennon, SJ (2003). «Body Image, Appearance Self-Schema, and Media Images». Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 32: 27–51. doi:10.1177/1077727X03255900.

- ↑ Simpson, KJ (2002). «Anorexia nervosa and culture». Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 9 (1): 65–71. doi:10.1046/j.1351-0126.2001.00443.x. PMID 11896858.

- ↑ Addolorato, G; Taranto, C; Capristo, E; Gasbarrini, G (1998). «A case of marked cerebellar atrophy in a woman with anorexia nervosa and cerebral atrophy and a review of the literature». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 24 (4): 443–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199812)24:4<443::AID-EAT13>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 9813771.

- ↑ Keel, PK; Klump, KL (2003). «Are eating disorders culture-bound syndromes? Implications for conceptualizing their etiology». Psychological Bulletin. 129 (5): 747–69. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.524.4493. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.747. PMID 12956542.

- ↑ Nevonen, L; Norring, C (2004). «Socio-economic variables and eating disorders: A comparison between patients and normal controls». Eating and Weight Disorders. 9 (4): 279–84. doi:10.1007/BF03325082. PMID 15844400.

- ↑ Polivy, J; Herman, CP (2002). «Causes of eating disorders». Annual Review of Psychology. 53: 187–213. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103. PMID 11752484.

- ↑ Essick, Ellen (2006). «Eating Disorders and Sexuality». In Steinberg, Shirley R.; Parmar, Priya; Richard, Birgit (eds.). Contemporary Youth Culture: An International Encyclopedia. Greenwood. էջեր 276–80. ISBN 978-0-313-33729-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ 10,0 10,1 Treasure, J; Claudino, AM; Zucker, N (2010). «Eating disorders». The Lancet. 375 (9714): 583–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61748-7. PMID 19931176.

- ↑ Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan (2014). abnormal psychology (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. էջեր 353–354. ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ↑ Naessén, S; Carlström, K; Garoff, L; Glant, R; Hirschberg, AL (2006). «Polycystic ovary syndrome in bulimic women—an evaluation based on the new diagnostic criteria». Gynecological Endocrinology. 22 (7): 388–94. doi:10.1080/09513590600847421. PMID 16864149.

- ↑ McCluskey, S; Evans, C; Lacey, JH; Pearce, JM; Jacobs, H (1991). «Polycystic ovary syndrome and bulimia». Fertility and Sterility. 55 (2): 287–91. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54117-X. PMID 1991526.

- ↑ Mash, Eric Jay; Wolfe, David Allen (2010). «Eating Disorders and Related Conditions». Abnormal Child Psychology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth: Cengage Learning. էջեր 415–26. ISBN 978-0-495-50627-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Schwitzer, AM (2012). «Diagnosing, Conceptualizing, and Treating Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified: A Comprehensive Practice Model». Journal of Counseling & Development. 90 (3): 281–9. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00036.x.

- ↑ Kim Willsher, Models in France must provide doctor's note to work Արխիվացված 2016-12-26 Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 18 December.

- ↑ 17,0 17,1 17,2 17,3 Romanos, GE; Javed, F; Romanos, EB; Williams, RC (October 2012). «Oro-facial manifestations in patients with eating disorders». Appetite. 59 (2): 499–504. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2012.06.016. PMID 22750232.

- ↑ Gailey, J (2009). «Starving is the most fun a girl can have: The Pro-Ana subculture as edgework». Critical Criminology. 17 (2): 93–108. doi:10.1007/s10612-009-9074-z.

- ↑ Arseniev-Koehler, Alina; Lee, Hedwig; McCormick, Tyler; Moreno, Megan A. (2016). «#Proana: Pro-Eating Disorder Socialization on Twitter». Journal of Adolescent Health. 58 (6): 659–664. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.02.012. PMID 27080731.

- ↑ Yu, U.-J. (2014). «Deconstructing College Students' Perceptions of Thin-Idealized Versus Nonidealized Media Images on Body Dissatisfaction and Advertising Effectiveness». Clothing and Textiles Research Journal. 32 (3): 153–169. doi:10.1177/0887302x14525850.

- ↑ 21,0 21,1 Ruffolo, J; Phillips, K; Menard, W; Fay, C; Weisberg, R (2006). «Comorbidity of Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Eating Disorders: Severity of Psychopathology and Body Image Disturbance». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 39 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1002/eat.20219. PMID 16254870.

- ↑ 22,0 22,1 Grant, JE; Kim, SW; Eckert, ED (November 2002). «Body dysmorphic disorder in patients with anorexia nervosa: prevalence, clinical features, and delusionality of body image». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 32 (3): 291–300. doi:10.1002/eat.10091. PMID 12210643.

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 Bulick, C; Hebebrand, J; Keski-Rahkonen, A; Klump, K; Reichborn, T; Mazzeo, SE; Wade, TD (2007). «Genetic Epidemiology, Endophenotypes, and Eating Disorder Classification». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40: S52–S60. doi:10.1002/eat.20398. PMID 17573683.

- ↑ 24,0 24,1 DeAngelis, T (2002). «A genetic link to anorexia». American Psychological Association. 33 (3): 34.

- ↑ 25,0 25,1 Klump, KL; Kaye, WH; Strober, M (2001). «The evolving genetic foundations of eating disorders». The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 24 (2): 215–25. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70218-5. PMID 11416922.

- ↑ Jimerson, DC; Lesem, MD; Kaye, WH; Hegg, AP; Brewerton, TD (1990). «Eating disorders and depression: is there a serotonin connection?». Biological Psychiatry. 28 (5): 443–54. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(90)90412-U. PMID 2207221.

- ↑ 27,0 27,1 Patel, P; Wheatcroft, R; Park, R; Stein, A (2002). «The Children of Mothers With Eating Disorders». Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 5 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1023/A:1014524207660. PMID 11993543.

- ↑ Blundell, JE; Lawton, CL; Halford, JC (1995). «Serotonin, eating behavior, and fat intake». Obesity Research. 3 Suppl 4: 471S–476S. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00214.x. PMID 8697045.

- ↑ Kaye, WH (1997). «Anorexia nervosa, obsessional behavior, and serotonin». Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 33 (3): 335–44. PMID 9550876.

- ↑ Bailer, UF; Price, JC; Meltzer, CC; Mathis, CA; Frank, GK; Weissfeld, L; McConaha, CW; Henry, SE; Brooks-Achenbach, S; Barbarich, NC; Kaye, WH (2004). «Altered 5-HT(2A) receptor binding after recovery from bulimia-type anorexia nervosa: relationships to harm avoidance and drive for thinness». Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (6): 1143–55. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300430. PMC 4301578. PMID 15054474.

- ↑ Frieling, H; Römer, KD; Scholz, S; Mittelbach, F; Wilhelm, J; De Zwaan, M; Jacoby, GE; Kornhuber, J; Hillemacher, T; Bleich, S (2010). «Epigenetic dysregulation of dopaminergic genes in eating disorders». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 43 (7): 577–83. doi:10.1002/eat.20745. PMID 19728374.

- ↑ George, DT; Kaye, WH; Goldstein, DS; Brewerton, TD; Jimerson, DC (July 1990). «Altered norepinephrine regulation in bulimia: effects of pharmacological challenge with isoproterenol». Psychiatry Res. 33 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(90)90143-S. PMID 2171006.

- ↑ Westen, D; Harnden-Fischer, J (2001). «Personality profiles in eating disorders: rethinking the distinction between axis I and axis II». The American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (4): 547–62. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.547. PMID 11282688.

- ↑ Rosenvinge, JH; Martinussen, M; Ostensen, E (2000). «The comorbidity of eating disorders and personality disorders: a meta-analytic review of studies published between 1983 and 1998». Eating and Weight Disorders. 5 (2): 52–61. doi:10.1007/bf03327480. PMID 10941603.

- ↑ Kaye, WH; Bulik, CM; Thornton, L; Barbarich, N; Masters, K (2004). «Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa». The American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (12): 2215–21. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215. PMID 15569892.

- ↑ Thornton, C; Russell, J (1997). «Obsessive compulsive comorbidity in the dieting disorders». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 21 (1): 83–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199701)21:1<83::AID-EAT10>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 8986521.

- ↑ Vitousek, K; Manke, F (1994). «Personality variables and disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa». Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 103 (1): 137–47. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.137. PMID 8040475.

- ↑ Braun, DL; Sunday, SR; Halmi, KA (1994). «Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with eating disorders». Psychological Medicine. 24 (4): 859–67. doi:10.1017/S0033291700028956. PMID 7892354.

- ↑ Spindler, A; Milos, G (2007). «Links between eating disorder symptom severity and psychiatric comorbidity». Eating Behaviors. 8 (3): 364–73. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.11.012. PMID 17606234.

- ↑ Collier, R (2010). «DSM revision surrounded by controversy». Canadian Medical Association Journal. 182 (1): 16–7. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3108. PMC 2802599. PMID 19920166.

- ↑ Kutchins, H; Kirk, SA (1989). «DSM-III-R: the conflict over new psychiatric diagnoses». Health & Social Work. 14 (2): 91–101. doi:10.1093/hsw/14.2.91. PMID 2714710.

- ↑ Busko, Marlene. «DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders May Be Too Stringent». Medscape. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2012-05-13-ին.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Murdoch, CJ (10 September 2009). «The Politics of Disease Definition: A Summer of DSM-V Controversy in Review. Stanford Center for Law and the Biosciences». Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 15 September 2010-ին.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ «Psychiatry manual's secrecy criticized». Los Angeles Times. 29 December 2008. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 23 January 2010-ին.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Casper, Regina C (1998). «Depression and eating disorders». Depression and Anxiety. 8 (Suppl 1): 96–104. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)8:1+<96::AID-DA15>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 9809221.

- ↑ Winston, AP; Barnard, D; D'souza, G; Shad, A; Sherlala, K (2006). «Pineal germinoma presenting as anorexia nervosa: Case report and review of the literature». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 39 (7): 606–8. doi:10.1002/eat.20322. PMID 17041920.

- ↑ Chipkevitch, E; Fernandes, AC (1993). «Hypothalamic tumor associated with atypical forms of anorexia nervosa and diencephalic syndrome». Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 51 (2): 270–4. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X1993000200022. PMID 8274094.

- ↑ Rohrer, TR; Fahlbusch, R; Buchfelder, M; Dörr, HG (2006). «Craniopharyngioma in a female adolescent presenting with symptoms of anorexia nervosa». Klinische Pädiatrie. 218 (2): 67–71. doi:10.1055/s-2006-921506. PMID 16506105.

- ↑ Chipkevitch, E (1994). «Brain tumors and anorexia nervosa syndrome». Brain & Development. 16 (3): 175–9. doi:10.1016/0387-7604(94)90064-7. PMID 7943600.

- ↑ Lin, L; Liao, SC; Lee, YJ; Tseng, MC; Lee, MB (2003). «Brain tumor presenting as anorexia nervosa in a 19-year-old man». Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, Taiwan Yi Zhi. 102 (10): 737–40. PMID 14691602.

- ↑ Conrad, R; Wegener, I; Geiser, F; Imbierowicz, K; Liedtke, R (2008). «Nature against nurture: calcification in the right thalamus in a young man with anorexia nervosa and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder». CNS Spectrums. 13 (10): 906–10. doi:10.1017/S1092852900017016. PMID 18955946.

- ↑ Burke, CJ; Tannenberg, AE; Payton, DJ (1997). «Ischaemic cerebral injury, intrauterine growth retardation, and placental infarction». Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 39 (11): 726–30. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07373.x. PMID 9393885.

- ↑ Cnattingius, S; Hultman, CM; Dahl, M; Sparén, P (1999). «Very preterm birth, birth trauma, and the risk of anorexia nervosa among girls». Archives of General Psychiatry. 56 (7): 634–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.634. PMID 10401509.

- ↑ Biederman, J; Ball, SW; Monuteaux, MC; Surman, CB; Johnson, JL; Zeitlin, S (2007). «Are girls with ADHD at risk for eating disorders? Results from a controlled, five-year prospective study». Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP. 28 (4): 302–7. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3180327917. PMID 17700082.

- ↑ Favaro, A; Tenconi, E; Santonastaso, P (2008). «The relationship between obstetric complications and temperament in eating disorders: a mediation hypothesis». Psychosomatic Medicine. 70 (3): 372–7. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318164604e. PMID 18256341.

- ↑ Decker, MJ; Hue, GE; Caudle, WM; Miller, GW (2003). «Episodic neonatal hypoxia evokes executive dysfunction and regionally specific alterations in markers of dopamine signaling». Neuroscience. 117 (2): 417–25. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00805-9. PMID 12614682.

- ↑ Decker, MJ; Rye, DB (2002). «Neonatal intermittent hypoxia impairs dopamine signaling and executive functioning». Sleep & Breathing. 6 (4): 205–10. doi:10.1007/s11325-002-0205-y. PMID 12524574.

- ↑ Scher, MS (2003). «Fetal and neonatal neurologic case histories: assessment of brain disorders in the context of fetal-maternal-placental disease. Part 1: Fetal neurologic consultations in the context of antepartum events and prenatal brain development». Journal of Child Neurology. 18 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1177/08830738030180020901. PMID 12693773.

- ↑ Podar, I; Hannus, A; Allik, J (1999). «Personality and affectivity characteristics associated with eating disorders: a comparison of eating disordered, weight-preoccupied, and normal samples». Journal of Personality Assessment. 73 (1): 133–47. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA730109. PMID 10497805.

- ↑ Burke, CJ; Tannenberg, AE (1995). «Prenatal brain damage and placental infarction- an autopsy study». Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 37 (6): 555–62. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1995.tb12042.x. PMID 7789664.

- ↑ Squier, M; Keeling, JW (1991). «The incidence of prenatal brain injury». Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 17 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.1991.tb00691.x. PMID 2057048.

- ↑ Al Mamun, A; Lawlor, DA; Alati, R; O'Callaghan, MJ (2006). «Does maternal smoking during pregnancy have a direct effect on future offspring obesity? Evidence from a prospective birth cohort study». American Journal of Epidemiology. 164 (4): 317–25. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj209. PMID 16775040.

- ↑ Iidaka, T; Matsumoto, A; Ozaki, N; Suzuki, T; Iwata, N (2006). «Volume of left amygdala subregion predicted temperamental trait of harm avoidance in female young subjects. A voxel-based morphometry study». Brain Research. 1125 (1): 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.015. PMID 17113049.

- ↑ Pritts, SD; Susman, J (2003). «Diagnosis of eating disorders in primary care». American Family Physician. 67 (2): 297–304. PMID 12562151.

- ↑ Gelder, Mayou, Geddes (2005). Psychiatry: Page 161. New York, NY; Oxford University Press Inc.

- ↑ O'Brien, A; Hugo, P; Stapleton, S; Lask, B (2001). «"Anorexia saved my life": coincidental anorexia nervosa and cerebral meningioma». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 30 (3): 346–9. doi:10.1002/eat.1095. PMID 11746295.

- ↑ 67,0 67,1 Satherley R, Howard R, Higgs S (Jan 2015). «Disordered eating practices in gastrointestinal disorders». Appetite (Review). 84: 240–50. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.006. PMID 25312748.

- ↑ 68,0 68,1 68,2 Bern EM, O'Brien RF (Aug 2013). «Is it an eating disorder, gastrointestinal disorder, or both?». Curr Opin Pediatr (Review). 25 (4): 463–70. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e328362d1ad. PMID 23838835. «Several case reports brought attention to the association of anorexia nervosa and celiac disease.(...) Some patients present with the eating disorder prior to diagnosis of celiac disease and others developed anorexia nervosa after the diagnosis of celiac disease. Healthcare professionals should screen for celiac disease with eating disorder symptoms especially with gastrointestinal symptoms, weight loss, or growth failure.(...) Celiac disease patients may present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, vomiting, abdominal pain, anorexia, constipation, bloating, and distension due to malabsorption. Extraintestinal presentations include anemia, osteoporosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, short stature, delayed puberty, fatigue, aphthous stomatitis, elevated transaminases, neurologic problems, or dental enamel hypoplasia.(...) it has become clear that symptomatic and diagnosed celiac disease is the tip of the iceberg; the remaining 90% or more of children are asymptomatic and undiagnosed.»

- ↑ Quick VM, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Neumark-Sztainer D (May 1, 2013). «Chronic illness and disordered eating: a discussion of the literature». Adv Nutr (Review). 4 (3): 277–86. doi:10.3945/an.112.003608. PMC 3650496. PMID 23674793.

- ↑ 70,0 70,1 Caslini, M; Bartoli, F; Crocamo, C; Dakanalis, A; Clerici, M; Carrà, G (January 2016). «Disentangling the Association Between Child Abuse and Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis». Psychosomatic Medicine. 78 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000233. PMID 26461853.

- ↑ Troop, NA; Bifulco, A (2002). «Childhood social arena and cognitive sets in eating disorders». The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 41 (Pt 2): 205–11. doi:10.1348/014466502163976. PMID 12034006.

- ↑ Nonogaki, K; Nozue, K; Oka, Y (2007). «Social isolation affects the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes in mice». Endocrinology. 148 (10): 4658–66. doi:10.1210/en.2007-0296. PMID 17640995.

- ↑ Esplen, MJ; Garfinkel, P; Gallop, R (2000). «Relationship between self-soothing, aloneness, and evocative memory in bulimia nervosa». The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 27 (1): 96–100. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200001)27:1<96::AID-EAT11>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 10590454.

- ↑ Larson, R; Johnson, C (1985). «Bulimia: disturbed patterns of solitude». Addictive Behaviors. 10 (3): 281–90. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(85)90009-7. PMID 3866486.

- ↑ Fox, John (July 2009). «Eating Disorders and Emotions». Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 16 (237–239): 237–239. doi:10.1002/cpp.625. PMID 19639648.

- ↑ Johnson, JG; Cohen, P; Kasen, S; Brook, JS (2002). «Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood». The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (3): 394–400. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.394. PMID 11870002.

- ↑ Klesges, RC; Coates, TJ; Brown, G; Sturgeon-Tillisch, J; Moldenhauer-Klesges, LM (1983). «Parental influences on children's eating behavior and relative weight». Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 16 (4): 371–8. doi:10.1901/jaba.1983.16-371. PMC 1307898. PMID 6654769.

- ↑ Galloway, AT; Fiorito, L; Lee, Y; Birch, LL (2005). «Parental Pressure, Dietary Patterns, and Weight Status among Girls Who Are "Picky Eaters"». Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 105 (4): 541–8. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.01.029. PMC 2530930. PMID 15800554.

- ↑ Jones, C; Harris, G; Leung, N (2005). «Parental rearing behaviours and eating disorders: the moderating role of core beliefs». Eating Behaviors. 6 (4): 355–64. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.05.002. PMID 16257809.

- ↑ Brown, R; Ogden, J (2004). «Children's eating attitudes and behaviour: a study of the modelling and control theories of parental influence». Health Education Research. 19 (3): 261–71. doi:10.1093/her/cyg040. PMID 15140846.

- ↑ Savage, JS; Fisher, JO; Birch, LL (2007). «Parental Influence on Eating Behavior: Conception to Adolescence». The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics : A Journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 35 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x. PMC 2531152. PMID 17341215.

- ↑ Adams, Gerald R.; Crane, Paul (1980). «An Assessment of Parents' and Teachers' Expectations of Preschool Children's Social Preference for Attractive or Unattractive Children and Adults». Child Development. 51 (1): 224–231. doi:10.2307/1129610. JSTOR 1129610.

- ↑ Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan. Abnormal Psychology, 6e. McGraw-Hill Education, 2014. p. 359-360.

- ↑ Schreiber, GB; Robins, M; Striegel-Moore, R; Obarzanek, E (1996). «Weight modification efforts reported by black and white preadolescent girls: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study». Pediatrics. 98 (1): 63–70. PMID 8668414.

- ↑ Page, RM; Suwanteerangkul, J (2007). «Dieting among Thai adolescents: having friends who diet and pressure to diet». Eating and Weight Disorders : EWD. 12 (3): 114–24. doi:10.1007/bf03327638. PMID 17984635.

- ↑ McKnight, Investigators (2003). «Risk factors for the onset of eating disorders in adolescent girls: results of the McKnight longitudinal risk factor study». The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (2): 248–54. doi:10.1176/ajp.160.2.248. PMID 12562570.

- ↑ Paxton, SJ; Schutz, HK; Wertheim, EH; Muir, SL (1999). «Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls». Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 108 (2): 255–66. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.108.2.255. PMID 10369035.

- ↑ Rukavina, T; Pokrajac-Bulian, A (2006). «Thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction and symptoms of eating disorders in Croatian adolescent girls». Eating and Weight Disorders : EWD. 11 (1): 31–7. doi:10.1007/bf03327741. PMID 16801743.

- ↑ [ Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan (2014). (Ab)normal psychology. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. p. 323. 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ↑ Knauss, Christine; Paxton, Susan J.; Alsaker, Françoise D. (2007). «Relationships amongst body dissatisfaction, internalisation of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media in adolescent girls and boys». Body Image. 4 (4): 353–360. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.06.007. PMID 18089281.

- ↑ Garner, DM; Garfinkel, PE (2009). «Socio-cultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa». Psychological Medicine. 10 (4): 647–56. doi:10.1017/S0033291700054945. PMID 7208724.

- ↑ Eisenberg, ME; Neumark-Sztainer, D; Story, M; Perry, C (2005). «The role of social norms and friends' influences on unhealthy weight-control behaviors among adolescent girls». Social Science & Medicine. 60 (6): 1165–73. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.055. PMID 15626514.

- ↑ Jung, J; Lennon, SJ (2003). «Body Image, Appearance Self-Schema, and Media Images». Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 32: 27–51. doi:10.1177/1077727X03255900.

- ↑ Simpson, KJ (2002). «Anorexia nervosa and culture». Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 9 (1): 65–71. doi:10.1046/j.1351-0126.2001.00443.x. PMID 11896858.

- ↑ 95,0 95,1 Soh, NL; Touyz, SW; Surgenor, LJ (2006). «Eating and body image disturbances across cultures: A review». European Eating Disorders Review. 14 (1): 54–65. doi:10.1002/erv.678.

- ↑ Keel, PK; Klump, KL (2003). «Are eating disorders culture-bound syndromes? Implications for conceptualizing their etiology». Psychological Bulletin. 129 (5): 747–69. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.524.4493. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.747. PMID 12956542.

- ↑ Nevonen, L; Norring, C (2004). «Socio-economic variables and eating disorders: A comparison between patients and normal controls». Eating and Weight Disorders. 9 (4): 279–84. doi:10.1007/BF03325082. PMID 15844400.

- ↑ Polivy, J; Herman, CP (2002). «Causes of eating disorders». Annual Review of Psychology. 53: 187–213. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103. PMID 11752484.

- ↑ Essick, Ellen (2006). «Eating Disorders and Sexuality». In Steinberg, Shirley R.; Parmar, Priya; Richard, Birgit (eds.). Contemporary Youth Culture: An International Encyclopedia. Greenwood. էջեր 276–80. ISBN 978-0-313-33729-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ DeMonte, Alexandria. «Beauty Pageants». M.E. Sharpe. Վերցված է 24 September 2013-ին.(չաշխատող հղում)

- ↑ Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan (2014). abnormal psychology (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. էջեր 353–354. ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ↑ 102,0 102,1 Burton, CL; Allomong, TW; Halkitis, PN; Siconolfi, D (2009). «Body Dissatisfaction and Eating Disorders in a Sample of Gay and Bisexual Men». International Journal of Men's Health. 8 (3): 254–64. doi:10.3149/jmh.0803.254.

- ↑ Harrell, WA; Boisvert, JA (2009). «Homosexuality as a Risk Factor for Eating Disorder Symptomatology in Men». The Journal of Men's Studies. 17 (3): 210–25. doi:10.3149/jms.1703.210.

- ↑ Mash, Eric Jay; Wolfe, David Allen (2010). «Eating Disorders and Related Conditions». Abnormal Child Psychology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth: Cengage Learning. էջեր 415–26. ISBN 978-0-495-50627-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (օգնություն) - ↑ Schwitzer, AM (2012). «Diagnosing, Conceptualizing, and Treating Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified: A Comprehensive Practice Model». Journal of Counseling & Development. 90 (3): 281–9. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00036.x.

- ↑ Kim Willsher, Models in France must provide doctor's note to work Արխիվացված 2016-12-26 Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 18 December.